South Africa

Media sticking in government’s craw: An excerpt from ‘Who Rules South Africa?’

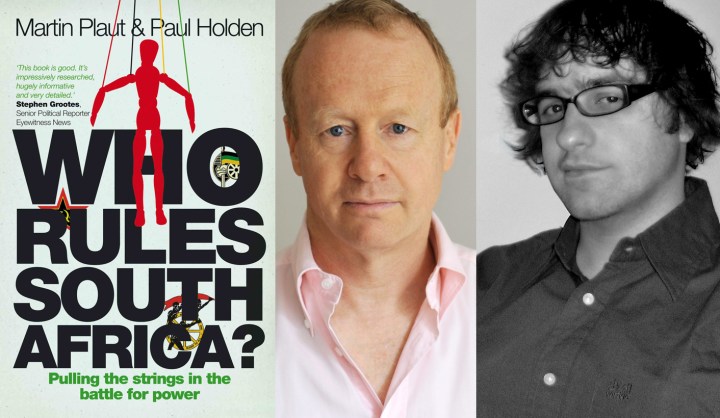

There’s good reason why the ruling party is at war with South Africa’s newspapers. During the past 15 years, almost all of the scandals that have rocked the rulers of the ANC have been broken by the likes of The Sunday Times, Mail & Guardian and City Press. In this extract from Who Rules South Africa?, authors Paul Holden and Martin Plaut look at the feud between those who claim to serve this country’s people, and those who are checking to see whether it’s true – the press. Introduction by MANDY DE WAAL.

Jackie Selebi may have been given a get-out-of-jail-free-card, but his every move is being scrutinised by the people who put him there – the South African press. The paper that first broke news of the Selebi scandal questioned the validity of his parole, reminding people of another felon that had been “sent home to die”, but who would languish on golf courses instead. “The reaction to the parole ruling of Jackie Selebi has shown the shadow of Schabir Shaik is still haunting South Africa’s medical parole procedure,” the Mail & Guardian declared.

The press became an object of extreme irritation for Shaik, given that after his parole they followed him everywhere, watching and reporting on his every move; the same will happen to Selebi.

The Selebi saga clearly shows why the editors of SA’s independent press are a thorn in the side of a ruling party. Holden and Plaut say that in a country where power is all about a battle for resources, newspapers aren’t just the fourth estate – they’ve become civic activists if not protectors of the Constitution.

Holden and Plaut’s new book Who rules South Africa? Pulling the strings in the battle for power, is all about that complex, ever-changing machine that is the political leadership of this country; and in this extract, the authors reveal the underbelly of the embattled relationship between SA’s ruling factions and their arch rivals, the press.

—

Extract from Who Rules South Africa? by Paul Holden and Martin Plaut

“Outside of the direct political control of the ruling party, the independent media have retained their fierce autonomy, despite frequent and robust criticisms being directed in their direction by senior ANC members. Indeed, if anything, the independent print media, and especially titles such as the Mail & Guardian, City Press, Sunday Times and Beeld, have become increasingly trenchant in the face of heavy-handed attacks and the deluge of corruption stories and allegations of government malfunction. Indeed, many media practitioners now view the role of the media as more than simply reporting the news or providing insight into government activities; instead, it should be actively involved in exposing abuses of power. Ray Hartley, the current editor of the Sunday Times, for example, believes the media should fill a multiplicity of roles: ‘I think that we do see the media as having an obligation beyond simply reporting. We have a constitution which tries to encourage the society to go somewhere, to build a democratic nation, to increase the empowerment of ordinary people. It is an activist constitution in that sense. And we would see ourselves in tune with that. But the primary mission remains to unflinchingly report the news. And, as a weekly newspaper, to break news and to expose abuses of power.’

For Nic Dawes, the editor of the Mail & Guardian, these roles – to inform, to act as a mechanism of accountability and as a forum for an exchange of ideas – are not merely identified by an arrogant media elite keen to extol their own virtues. Instead, the role of the media in assuring accountability is fundamental to South Africa’s constitutional democracy: ‘The Constitutional scheme is very clear. South African democracy functions both by having a properly designed state with appropriate roles for the executive, judiciary and parliament, and by making space for a range of other mechanisms of engagement and accountability that overlap with the institutions of the state. This is one reason that the media is given a special place in the constitutional architecture first of all as a mechanism of accountability, and also, and no less importantly, as a forum for the exchange and testing of ideas and the development of the proper democratic public sphere.’

When it has come to exposing abuses of power, the print media has a remarkable record. Almost all of the major corruption scandals that have surfaced over the last 15 years have been investigated and broken by the print media. Its continued attention to the topics, and dedication to uncovering as much of each sordid story as possible, has often been solely responsible for South Africans gaining a modicum of insight into each situation. The examples of the Arms Deal, the police leasing scandal and the Jackie Selebi corruption story are clear statements of how the media has played a vital democratic role in forcing a modicum of accountability. In each of these, media attention has empowered those in the justice cluster to pursue the cases despite their political awkwardness. As a result, the Arms Deal is now subject to a Commission of Inquiry; the police leasing scandal is currently under investigation and prompted the suspension of the Chief of Police; and Jackie Selebi is currently serving a lengthy term after being found guilty of corruption. [Selebi has recently been released on medical parole – Ed]

But perhaps the best example of how the media has been able to force the state to fulfil its democratic functions has been the Oilgate saga. Suffice to say that that saga involved the ANC allegedly agreeing to supply political support to Saddam Hussein’s beleaguered Iraq in return for favourable oil allocations. The allocations and their sale were overseen by the late Sandi Majali, who was alleged to have repaid the ANC for its political support by diverting some of the Oilgate funds into the ANC’s books. The story was first broken by the Mail & Guardian in the face of severe pressure: Majali’s company, Imvume, successfully sought a temporary interdict to prevent publication, only for the information later to be made available in Parliament by the Freedom Front. Over the course of the next few years, the newspaper was able to unravel the deal’s sordid conduct, in the process fingering such luminaries as Kgalema Motlanthe.

It seemed, for a while, that it might have been a pyrrhic endeavour. The allegations were forwarded for investigation to the Public Protector, who found that ‘much of what has been published in the Mail & Guardian was factually incorrect, based on incomplete information and documentation and comprised unsubstantiated suggestions and unjustified speculation’. Upset by the finding, the Mail & Guardian approached the High Court for relief. The Court found that the Public Protector’s investigation was of dubious quality. In June 2011, the High Court’s judgment was upheld by the Supreme Court of Appeal, which found that the Public Protector’s ‘investigation was so scant as not to have been an investigation, and there was no proper basis for any findings that were made’. As a result, the Public Protector’s report was set aside, meaning that the allegations would have to (be) reinvestigated afresh, which the current incumbent, Thuli Madonsela, has indicated she will do. By investigating the Oilgate scandal and challenging the Public Protector, the Mail & Guardian not only served democracy by providing access to information that many within the ANC would rather not have seen published, but also made great strides in ensuring that the Public Protector properly performed its role as envisaged in the Constitution. It would be hard to imagine any future investigation by the Public Protector cutting corners so obviously or behaving in a manner apparently so biased towards the ruling party – a major victory for democratic governance and accountability.

For both Nic Dawes and Ray Hartley, it is precisely the success of the independent print media in fulfilling its role of exposing the abuse of power that has led to the rapid deterioration in the relationship between the media and the ANC. Asked about when he felt the relationship between the media and the ruling party started fraying, Hartley was adamant: ‘I think it was when corruption at a very high level began to be exposed, particularly around Tony Yengeni who was then a rising star in the party. That’s when we got a lot of people who would have cooperated being a little bit on edge. And then I think that the whole unfolding Mbeki versus Zuma saga, which actually has its roots way back during Bulelani Ngcuka’s tenure, when the media started to expose and get involve in that, it was perceived as acting on the part of one faction and not the other, and the reverse. It became a very tense relationship from that point … Zuma for his part perceived the media to be acting against him in concert with Ngcuka and Mbeki to damage his public profile. And I think he bears that grudge to this day.’

During Mbeki’s tenure, attacks on the media were frequent and vicious, especially in his weekly ‘ANC Today’ column. ‘Mbeki acted as a one-man media tribunal in his Friday letter,’ Nic Dawes pithily notes. But, beyond these attacks, little attempt was made to directly bring the media within the ambit of government control. It was only in 2007, at the Polokwane Conference that elected Zuma as the new ANC president, that a resolution was passed supporting the creation of the so-called Media Appeals Tribunal. That resolution was fleshed out in more detail in a 2010 ANC discussion document, although even this remained vague: all that was clear was that the ANC supported the creation of a body (possibly based in Parliament) that would have the power to review the content of the media and seek remedy if it found that a media report was biased or an individual’s dignity was violated. Considering the ANC’s parliamentary majority, the judgments that such a body would reach when confronted with issues of bias in the representation of the ANC would be somewhat predictable.

To support the moves towards a Media Appeals Tribunal, the ANC has claimed that the media is under-regulated in South Africa. The Press Ombudsman, in particular, which is empowered to adjudicate complaints about press coverage and make orders that provide a measure of restorative justice, has been portrayed as little more than a press patsy, as the Ombudsman is usually an ex-editor or academic – conveniently ignoring that, if the Ombudsman’s decision is appealed, it is heard by a retired judge. As an attempt to undermine the Ombudsman’s credibility, the claim appears to have been unsuccessful. In February 2012, for example, the Ombudsman reported that there had been a 70 per cent increase in complaints to the Ombudsman from 150 in 2009 to 255 in 2011: hardly indicative of a body to which the public refused to turn. The Ombudsman also noted that the majority of the decisions it had reached had been in favour of the complainants and against the major media houses. ‘There are many times when I would much rather prefer to be in court than in front of the Press Ombudsman,’ Ray Hartley noted. ‘In many cases I feel I could have better defended a story legally than in front of the Ombudsman who has a looser, less legalistic approach.’

Hartley’s mention of legal defensibility raises another inconvenient fact: the press is already regulated in the form of defamation and privacy law, and is constrained, as are all private actors, by the dictates of criminal law. In addition, complaints can also be laid with both the Gender and Human Rights Commissions, and the Equality Court, which have the power to make determinations in relation to media articles. The media is also now subject to an additional level of scrutiny via the social media, which has proven incredibly robust in detecting errors and making them known. But perhaps the greatest regulator is credibility: if newspapers are considered to be overtly politically biased, unfair in coverage or consistently linked to incorrect information, the public is less likely to turn to those sources. ‘The New Age newspaper [funded by members of the Gupta family, which is reportedly close to Zuma, and launched in 2010] has mobilised vast resources, but it still doesn’t have great traction,’ Hartley argues. ‘It’s not a bad paper at all, but there is a suspicion that it will not give you the unvarnished truth. There is a culture of scepticism and it’s not surprising in a situation where the truth has been suppressed for so many decades.’

The Media Appeals Tribunal appears, on the face of it, to be a solution where there is no problem.” DM

Read more:

- The Dangers of Crying Wolf on Press Freedom by Jane Duncan at the The South African Civil Society Information Service

- His master’s voice: An excerpt from ‘Who Rules South Africa’? on Daily Maverick

- Requiem for a tragic antihero, Jackie Selebi by Ranjeni Munusamy on Daily Maverick

Become an Insider

Become an Insider