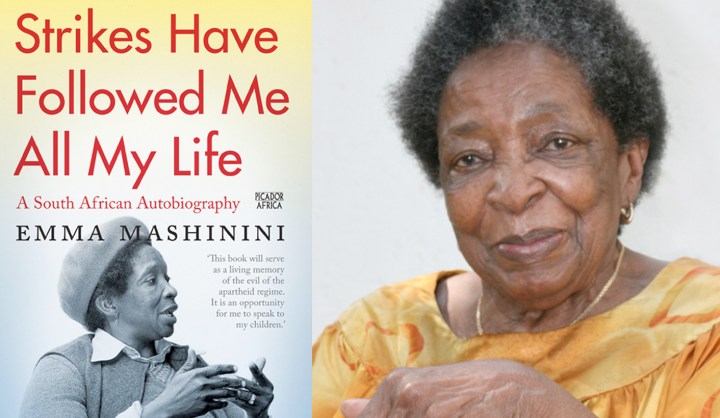

The lean, mean, labour rights Mashinini

Strikes Have Followed Me All My Life, the autobiography of South African trade unionist Emma Mashinini, has been brought out in a new edition this year to coincide with the 100th anniversary of the founding of the ANC. It’s been 23 years since the book was first published, but REBECCA DAVIS finds that it’s lost none of its power as an account that is both political and deeply personal.

Emma Mashinini is old enough, at 83, to have experienced a life inscribed virtually from its inception by the dictates of the apartheid state: her family had suffered two forced removals by the time she reached her teens.

Perhaps it’s unsurprising, then, that she started fighting young: at about 15, she describes “my first fight for human rights, my own right to have a father”. Mashinini’s father broke up her family when he separated from her mother. Despite the fact that this set in motion a chain of events that led to her leaving school and marrying at the age of 17, she records no bitterness: “I loved my father dearly,” she writes.

But having witnessed first-hand the destructive impact on a dependant woman when a man suddenly withdraws support, it was perhaps this event above all others in her formative life that we can point to as having shaped her extraordinarily independent spirit, and contributed to her profound belief in the need for equality between women and men.

When this edition of her book was launched by Pan Macmillan in May, Cosatu general secretary Zwelinzima Vavi said of Mashinini: “She showed that a woman’s place was not in the bedroom and the kitchen but in the forefront of the struggle. She is a woman made from an unbreakable mould.”

In Strikes Have Followed Me All My Life Mashinini comes across as a deeply pragmatic soul, one who entered the labour struggle more out of concerns for basic fairness – and an awareness that she could act as a good mediator – than out of any desire to become immortalised as a political firebrand.

“I have always resented being dominated,” she writes by way of explanation for her motives. “I resent being dominated by a man, and I resent being dominated by white people, be they man or woman. I don’t know if that is being politicised. It is just trying to say, ‘I am human. I exist. I am a complete person’.”

Indeed, the book actually contains relatively little mention of the wider struggle or goings-on in the ANC at the time: her focus is firmly on the rights of the workers. Giving evidence to the 1977 Wiehahn Commission into trade unions, however, Mashinini insisted that, in a South African context, the unions had to be involved in politics.

“This is a country where everything around us is politics,” she writes. “As they say, touch a black person and it’s politics.”

Mashinini’s introduction to the labour struggle came when she started working at a clothing factory called Henochsberg. She was horrified to recognise the camouflage outfits they were producing on the backs of the security police during the Soweto uprising in June 1976. She quickly rose to become the first black supervisor in the factory’s history, but being rewarded in this way did not lead her to look any more kindly on what she regarded as the gross injustices of conditions for black workers. The cushiest jobs, such as operating the lifts, were always reserved for whites, who were often either old or mentally disabled.

“Can you imagine what this means, that a retired and retarded white person was considered more valuable and productive than a young and competent black?”

She soon became angry. Her cynicism towards the motives of white people is a recurrent theme in the book. She protested against black workers in the factory being given TB tablets, for instance, because she suspected that some more sinister medical purpose underlay this. It was only when she realised white workers also received them that her concerns were allayed.

The company doesn’t sound any worse than other factories of the time – in some respects probably better. For instance, the owner arranged for Mashinini’s daughter to receive a university bursary. But that doesn’t stop some of the details still appearing chilling to a contemporary reader. In almost 20 years of service at the factory, she was never asked to sit down when addressing her employers. The highest rate her salary reached was R20 per week, and only R5 of this would be kept by the factory and handed over to her in a lump sum in January to allow her to pay her children’s school fees. It would be interesting to see how some of these conditions compare with the current status quo for factory workers. (Judging by an exposé in The Herald last year on a Uitenhage chicken factory, maybe things aren’t so different.)

When she left the clothing factory to start a union for black shop workers (the Commercial, Catering and Allied Workers’ Union of South Africa), she received daily exposure to the kinds of grievances workers had in the mid-70s, which, again, are likely not terribly different to those experienced today. Many times, what it seemed to come down to was a complete lack of understanding on the part of the employers about the structural difficulties workers faced in every area of life.

For instance, transport difficulties continually contributed to workers arriving late, for which they would be threatened with a sacking, even though there was very little they could do to avoid this – some of Mashinini’s co-workers would rise as early as 4am in order to travel as far as 60km to reach work. Another problem revolved around uniform cleanliness: workers would receive a warning for having a dirty uniform, but many could afford only one pair of overalls. These were the smaller battles Mashinini fought on behalf of shop workers. Others were more serious, particularly those to do with the rights of workers to organise at all.

After the 1977 Wiehahn Commission, the black unions were informed that they would be allowed to register officially for the first time. Mashinini records that this prompted a long and difficult debate among them about whether this was the right course of action, or whether it would be interpreted as a sign that they were colluding with the apartheid system. (This was another recurring fear of Mashinini’s: she repeatedly mentions her refusal to accept help or favours from security officials, or similar figures, out of anxiety that she would be assumed to be collaborating in some way.)

In the end, the unions decided to apply for registration in 1979. They were told their applications were under consideration. Then the crackdown on “difficult” leaders began.

Mashinini did not have too much time to worry about her personal safety, because these were dangerous times for unions anyway. In 1980, 12,000 workers fighting for the recognition of the Black Municipal Workers’ Union downed tools. Every one of them was sacked, forced on to buses by armed police and sent back to the homelands.

On 27 November 1981 Mashinini was arrested and held under Section 22, a provision of the Terrorism Act that permitted you to be held for 14 days without charge. When taken to the notorious John Vorster Square, she was asked in Afrikaans: “Are you a commie?” She misunderstood, presuming the cop meant “Are you a communicant of the church?” and replied: “Yes.” Her questioner responded angrily: “Well, I’m not going to give you the damned Bible, because you are a communist and you admit it.”

Mashinini assumed she would be released from Pretoria Central Prison within 14 days. Then a policewoman informed her that she was being held under Section 6, which provided for indefinite interrogation. Mashinini’s account of her confinement, during which she was kept in total isolation, is harrowing. But perhaps most frustrating was her confusion about why she was actually being detained in the first place.

“What was more horrible was that I had to ask a very junior policewoman, Why am I not going home?” she writes. “And this made me really feel something was wrong. What if I had not enquired? They may have just forgotten me when I was supposed to have gone home, and nobody would have come to tell me. I didn’t understand the law myself, but I really felt that there was something wrong in that I was not told what was going on. Then, you know, I really had to search myself: What did I do? What offence had I committed? In fact, no one ever told me that.”

Although Mashinini was only detained for 6 months, the period had a profoundly bruising psychological impact on her. What wore her down, other than loneliness and not knowing who might have been detained with her, was the arbitrariness of the prison regulations. She was allowed a total of exactly six Christmas cards in her cell, for instance. Her lowest ebb was hearing that her fellow trade unionist, Neil Aggett, had been found dead, hanging in his cell in detention. Following this additional trauma, she went through a period where she was unable to recall the name of her own daughter (Dudu) for weeks.

Mashinini was eventually transferred to a cell in Johannesburg, at Jeppe police station. Although conditions were in some way worse for her – she no longer had a bed, for instance – she was heartened by the presence of black security officials. Recounting this aspect, Mashinini doesn’t mince her words:

“But I was so glad – oh my God, I was glad – to see a black person, even a black policewoman. I was so sick of seeing those white people. To always see white people; white people pushing your food at you through the door; white people pushing you and telling you ‘Come’ or ‘Go’; and white people always telling you what to do – it was making me ill. Because when you are black you have a need for persons of your own colour. And with my envy of white people, now to be surrounded by them made me realise again how stupid that was, to envy their skin or hair. It was no privilege to be among them. It was a misery and a deprivation.”

When Mashinini was eventually released, she struggled hugely with what sounds like post-traumatic stress: every time she heard a car approaching her house, she thought it was the police coming to get her again. “These people know what they do when they lock you up,” she muses. “You torture yourself.” With the aid of international unionist colleagues, she ended up in a clinic in Denmark for international torture victims, though this seems to have been a mixed success.

But Mashinini returned to work, overseeing the growth of CCAWUSA to a union of over 60,000 members in only 10 years. The 80s were still a time when white employers could curtail the rights of their workers through the simple invocation of the phrase: “You’re cheeky”. And of course, the treatment of black females was particularly bad: her union had to fight the case of female workers who were tired of being subjected to humiliating vaginal and anal searches at work on the whims of white security.

Mashinini’s union also secured the right for women to return to work after maternity leave, and ensured that women were included in medical aid and pension funds for the first time. Nor were all their struggles for black workers: in 1983, workers at Checkers in Germiston went on strike to defend a white colleague who had been demoted, even though she was not a CCAWUSA member.

Ironically, despite the successes she won for other female workers, Mashinini was still excluded from selection for the national executive of Cosatu when the trade union federation was formed in 1985. She hints that this was a gender-based decision: “each and every one of (the names put forward) were men’s names”. She also took offence at the fact that the Cosatu logo initially featured only a man. (Now there are two men and a woman: “the workers who drive the economy and the woman with a baby, representing the triple challenges of economic exploitation, racial and gender oppression”, according to the Cosatu website.)

Mashinini has always maintained that gender equality is inextricably bound up with the struggle for worker’s rights, just as the struggle for worker’s rights is unavoidably connected to other aspects of life. “The trade unions have got to follow the workers in all their travels: to get them home and to school; in the education and welfare of their children; everywhere,” she writes. “And together with that goes the whole question of equality between men and women.”

Her personal life has been touched with tragedy several times. Three of her six children died in their infancy due to misdiagnosed jaundice. Her daughter, Penny, died in 1971, aged 17, in an incident Mashinini only mentions at the end of the book, and still cannot bring herself to supply any details about. Her son-in-law, Aubrey, was killed in 1988 while working as an undertaker as the result of some community members taking revenge after a Sowetan article incorrectly claimed that undertakers were abducting children.

“I’ve lived a hard life, in many ways a horrible life,” she writes with customary frankness at the book’s conclusion, from the vantage point of 1989. “But I have always wanted to see the day of liberation. And when we get there, as a coward, perhaps, I am prepared to die, to say: ‘I’ve lived and struggled for all these years. Now that we’ve achieved justice – now that we’ve attained that – now may I not rest in peace?”

Mashinini didn’t rest in peace after liberation, as it turned out. After serving as the first Director of the Anglican Church’s Department of Justice and Reconciliation, she went on to serve as a Commissioner for Land Restitution before retiring in 2003. In August she will turn 83, Jay Naidoo notes in a foreword to this new edition. “She remains militant, speaking out fearlessly against corruption and the lack of service delivery, whether it be in government, the private sector or the labour movement to which she has dedicated her life’s work.”

It is a pity that some of that fearless speaking-out is not collected in this new edition, in however abbreviated a form. The fact that the narrative ends in 1989 leaves us with intriguing questions unanswered: what does Mashinini think of the democratic transition? What does she make of the ANC’s relationship with Cosatu?

All we are given is a paragraph in the new acknowledgements in which she states: “I am deeply concerned about what is happening, especially in terms of education, health and the negligence of the elderly, particularly those who have served the country and are now forgotten. It is important that we continue to give back, and that we do not get too obsessed with the shine.”

Mashinini herself, of course, is one of the elderly who has served the country and whose story risks being forgotten or overshadowed by the stories of those currently in the seats of power. That would be an enormous pity, because what Strikes Have Followed Me All My Life makes clear is that Mashinini’s work for labour rights in South Africa has been undertaken at enormous personal cost, and in a spirit of courage which should be nothing short of inspirational. DM

Photo and book cover by PanMacmillan.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider