Africa

One year later, the Sudans are still reeling from their messy divorce

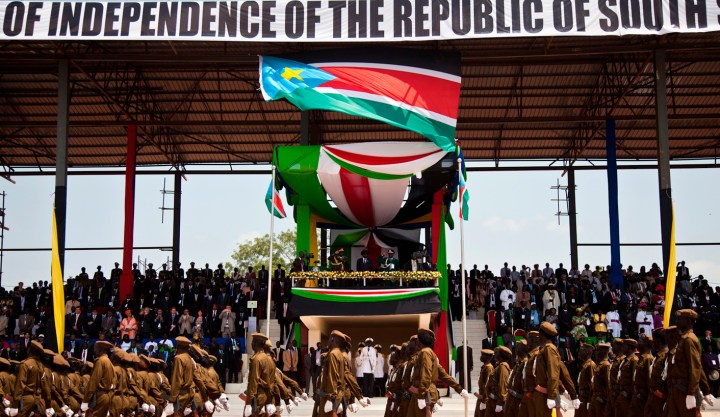

It’s been a year since South Sudan raised its new flag in Juba, becoming the world’s newest country and leaving the rest of Sudan to fend for itself. The separation has not been easy. SIMON ALLISON assesses the state of the troubled nations.

You might think the political situation in the Sudans has little to do with the divorce of Tom Cruise and Katie Holmes, and you’d be right. But there are a couple of similarities that even a serious and upstanding journalist like myself can’t ignore. First, that slightly crazy religious fundamentalists make for prickly partners, in both government and matrimony, and that break-ups are invariably messy and expensive.

TomKat are finding this out the hard way, under the gaze of exponentially more media attention than even Sudan’s very worst excesses could muster. Juba and Khartoum, meanwhile, have had exactly a year to get over their own divorce, and are finding that life apart brings its own set of complications.

Nonetheless, the South Sudanese government in Juba and the country’s ruling party, the Sudan Peoples’ Liberation Movement, opted to celebrate the anniversary of their secession on Monday.

“South Sudan is a gift from God and confirmed by the blood of our martyrs,” read a typically florid party press release to commemorate the occasion. “The SPLM-led government will take care of it and will be (sic) handed over from generation to generation until the end of the world.”

The party was keen to trumpet the government’s successes over the last year, pointing out initiatives to increase women’s participation in government, get more children into schools, improve access to drinking water and provide vaccinations against “folio” (sic), a new disease created by poor quality proof-reading in the party’s communications department.

The reality is a little less rosy. In his country’s first speech before the United Nations in September, President Salva Kiir pointed out that South Sudan needed to start from scratch. “Even before the ravages of war could set in, our country never had anything worth rebuilding,” he said. “Our march out of the abyss of poverty and deprivation into the realm of progress and prosperity is going to be a long one…”

But Kiir had a plan. With his trademark black cowboy hat firmly in place, the president told the United Nations that South Sudan would use oil as a “catalyst to unlock the potential we have in other areas”. Fully aware that it would run out at some point, the idea was to take advantage of the oil revenue to build up agriculture and industry, making Sudan eventually self-sufficient.

This plan was stalled – perhaps fatally – by the government’s decision in January to completely shut down oil production. Understandably tired of having to pipe all its oil through Sudan proper and thus pay exorbitant transit fees to the Khartoum regime, Juba instead decided to wait until new pipelines were built to take the oil to Kenyan ports instead.

This decision, whether it was properly thought through or announced in a fit of pique after more stalled negotiations with Sudan proper, has already had a monumental impact on the government’s ability to govern. Oil revenues accounted for 98% of government revenue – essentially all of it – and without it South Sudan is barely able to stave off bankruptcy. Development is out of the question.

So, far from ushering in a glorious era in South Sudan’s history, independence has left the country in limbo. With no new pipelines under construction, and talks with Sudan going nowhere, their long-suffering citizens can expect things to get worse before they get better.

Things aren’t any rosier north of the border, in what remains of the old Sudanese state. While the regime in Khartoum might be enjoying South Sudan’s teething problems, the schadenfreude of President Omar al-Bashir and his cronies has been dampened considerably by problems of their own. There’s the Darfur rebellion, of course, which has been waxing and waning for a decade now. There’s the rebellion in the ‘new south’, on the border with South Sudan, where the remnants of the old southern rebel movement have been causing havoc as they fight to topple Bashir’s government. Then there’s the border squabbles with South Sudan, which occasionally threaten to ignite a devastating war between the two countries, and have already caused hundreds of thousands of refugees to flee Sudan into an uncertain future in the south.

But most serious of all are the protests coming from within Bashir’s traditional sources of power: the military, the party and the people in his heartland of central Sudan. The military wants more money and equipment, arguing it is not ready to fight the wars that Khartoum wants it to. This was seemingly proved by the army’s comprehensive and completely unexpected defeat to southern forces during an attack on the Sudanese oil field of Heglig in April (southern troops later withdrew after a combination of diplomatic and military pressure).

The party is jostling for position in anticipation of Bashir stepping down in 2015, and the infighting has already claimed its first major scalp: Salah Gosh, former intelligence head and presidential advisor, who was sacked in April after displaying what a National Congress Party spokesman described as “presidential ambitions”. Analysts see this as evidence of an increasingly fragmented ruling party, and probably the most serious challenge to the power of Bashir personally, if not the regime itself.

The regime’s biggest threat comes from the people, who have made their displeasure clear in recent times with a series of protests in Khartoum, Omdurman and other central Sudanese cities. Led mainly by students, the demonstrations have been relatively small (in the hundreds at most) and have no focal point. Reports indicate that they have been dispersed quickly by security forces, and up to 2,000 people have been arrested as a result. The protests were sparked by a government decision to scrap long-held fuel subsidies, doubling the price of petrol overnight – a sure-fire way to get angry mobs to burn things, as Nigeria found out earlier this year when it tried to remove fuel subsidies.

But the government had little choice. Its coffers have been emptied by the secession because South Sudan took with it most of the lucrative oil fields. And now that South Sudan isn’t even paying transit fees on its oil, Khartoum is really suffering. The subsidy removal is part of a package of austerity measures which Bashir has had to introduce. No one likes austerity measures, but they are particularly dangerous for Bashir’s government because they violate the unwritten but tacitly understood social contract which binds central Sudan together: that citizens will put up with a brutal, repressive and corrupt government in return for certain standard-of-living guarantees, chief among them cheap petrol and cheap bread. Take away those guarantees and suddenly that social contract becomes very flimsy indeed.

One year on, it’s fair to say that the south’s secession has not proved to be the hoped-for panacea to anyone’s problems. The divorce, in fact, has been just as messy as the union that preceded it. Neither of the Sudans is in a better position than they were last year. Economically, both are demonstrably worse and have little cause for optimism in the short term.

This won’t change in the long term, unless both countries realise that new flags and new borders don’t solve decades-old problems, and that even as separate entities they’ll have to work together to guarantee both of their futures. DM

Read more:

- South Sudan marks first anniversary of independence in wary mood in the Guardian

- The Sudanese doth protest too much: how austerity could, finally, undo Bashir on Daily Maverick

Photo by Reuters

Become an Insider

Become an Insider