South Africa

Death of a (textbook) salesman: Motshekga blames the supplier

Just when the scandal over textbooks delivery in Limpopo seems to be dying down, hundreds of new workbooks are found floating in a river and basic education minister, Angie Motshekga, denies being a “petty pathetic liar” in a letter worthy of a teenager’s diary. ALEX ELISEEV explores.

Monday threatened to be a fairly quiet day on the Limpopo textbooks front.

Basic Education minister, Angie Motshekga, took some serious flak in the Sunday newspapers, but the focus was shifting to the catch-up programme and to the delivery audit being managed by professor Mary Metcalfe.

The Democratic Alliance was protesting in Polokwane – going for the whole “never and never again” vibe – but aside from that, it seemed the storm had mostly blown over, at least for the time being.

Six months into the year, and after missing at least two deadlines, the department claimed to have supplied books to all schools in the troubled province. Rights group Section 27 (which took government to court) was receiving somewhat different reports from the ground. Metcalfe’s team requested two weeks to find out what was really going on. Despite only being appointed at the weekend, the team had already met with government and Section 27 to present its plan and to hear suggestions.

The department maintained its plans for the catch-up programme are in place, the study guides are printed and the only outstanding issue is getting the teacher unions on board. While some critics called the plan a disgrace, spokesman Panyaza Lesufi was adamant it was more than just forcing pupils to study in their free time. Asked whether they could make it work, he replied:

“We have more to lose if we don’t. So we don’t have a choice. We just have to pull that rabbit out of a hat.”

During the same morning, and rather unexpectedly, the department sent out a press release about hundreds of workbooks being dumped in a Limpopo river.

It appears the police alerted government about the discovery that same morning, not long after reports emerged that other books (Shakespeare novels and Nelson Mandela’s biographies amongst them) were being destroyed at a warehouse nearby.

The latest workbooks were not part of the batch that were frantically being delivered last week, but were apparently destined for grades eight and nine. The department laid the blame at the door of a supplier, saying criminal charges were being laid. It went further and described the dumping as an act of sabotage.

“There is no way when we are under this pressure someone decides to throw books into the river,” Lesufi fumed. “We’ve instructed the police: go and get these particular people. The only place they truly belong is not only jail, is hell.”

Lesufi’s powerful words clearly show how emotional the topic has become and the extent of the siege against Motshekga and her department. Or, in his own words, the level of pressure they are under.

Lesufi went on to deny that the minister lied about knowing a key whistleblower in the saga (who reportedly raised the alarm last year about the irregular textbook tender).

Speaking on Talk Radio 702 last week, Motshekga claimed she did not know the name Solly Tshitangano. On Sunday, the City Press printed some of the letters he had sent to government and the responses he had received.

But Lesufi argued that, in his capacity as advisor, he was the one who handled those letters, passing them onto the relevant authorities. He explained that Motshekga received hundreds of emails a day and did not deal with that particular issue. He added that even if she had been made aware of the irregularities, which she wasn’t, she couldn’t force a province to cancel a contract anyway, because the country’s law doesn’t work like that.

“To brand my minister as a liar is pushing it too far,” he said. “And it’s not based on any fact.”

It soon turned out his minister didn’t need much defending, because she had written an open letter to defend herself.

Some called it “cocky” while others felt it was raw with emotion. Whichever it was, the letter was so unusual we had to double-check if it was genuine.

In essence, it was a response to a series of articles that questioned whether a former Limpopo education official, Anis Karodia, was fired or left voluntarily.

Motshekga claimed she axed Karodia but was accused of lying and of making him the “fall guy”. Newspapers got their hands on a letter she allegedly sent him, praising him for a job well done.

It was this sharp contradiction that Motshekga devoted most of her letter to, aside from attacking journalists and asking to be given the right to reply.

Motshekga begins by reaffirming that she’s not about to resign over the textbook crisis.

“I have no doubt that indeed not only am I capable of fulfilling my responsibilities but with the current team, we have been to steer well this ship in its troubled waters (sic).”

She goes on to claim that Karodia was allowed to send letters to the press as part of his settlement agreement, which was reached to avoid an ugly labour dispute.

“All I needed at the time was to see him out of the province and a new administrator appointed to replace him.”

Motshekga dares Karodia to publicly reveal the reasons for his departure – or to let her do it – and to tell the truth. It will be interesting to see if he takes the bait.

But the most revealing part of the letter came halfway through the second page, where Motshekga spoke directly to a newspaper.

“It is unfortunate that your editorial confirms the depiction… made of me – a petty pathetic liar desperate to save [her] own skin at the expense of others. As mentioned earlier I would not say that I gave instructions that Dr Karodia be removed as head of the Limpopo intervention team when that was not true. At least I respect myself enough not to stoop that low,” she writes. “The person written about cannot be the person I know myself to be. Thanks to my age, I am at a stage where there are very few things that I don’t know about myself, so the (newspaper) and Karodia could not be more wrong about me and the stupid things I’m capable of.”

Motshekga goes on to say that she has never used anyone as a shield and ends on a dramatic note by asking the media to give her a chance to “state my case” when being accused of incompetence.

“I guess that is not too much to ask,” she concludes.

No one can deny that Motshekga has taken an unprecedented amount of criticism over the textbooks, and perhaps rightfully so. She’s always claimed it was not her fault and that Limpopo’s mismanagement and possible corruption is to blame. But the public didn’t see it that way, while the media accused her of ignoring important warnings.

Her letter may prove to have been a bad move. It’s naked, raw and filled with spelling and grammar mistakes. Its message (which is important) is almost drowned out by the emotion. In short, it’s not the kind of communication one expects from a minister, and she probably would have done herself a favour by sleeping on it another night.

Clearly, Motshekga and her department have the right to defend themselves and try set the record straight, but it’s all about how this is done and what results are achieved. The perception of being in control is, at times, as important as actually being in control.

The letter was not well received on social networks. The replies poured in immediately: “Can madam Angie stop with the excuses already”; “My 7-year-old could give her stiff competition at writing a letter”; “Is she playing with fridge poetry?”; “She has delusions of adequacy”.

Whether these are fair or not, they show that the situation is far too tense to introduce poorly articulated thoughts.

And whether she likes it or not, Motshekga is the captain of the education ship. While she’s doing the honourable thing by not jumping into a lifeboat, the “troubled waters” she writes about remain a swamp of soggy textbooks being dumped by unscrupulous service providers.

There’s a long way to go in cleaning up this mess and making sure pupils make it through this year and that textbooks are properly ordered for 2013. The last thing her ship needs now is a sign that the captain is cracking under the pressure. DM

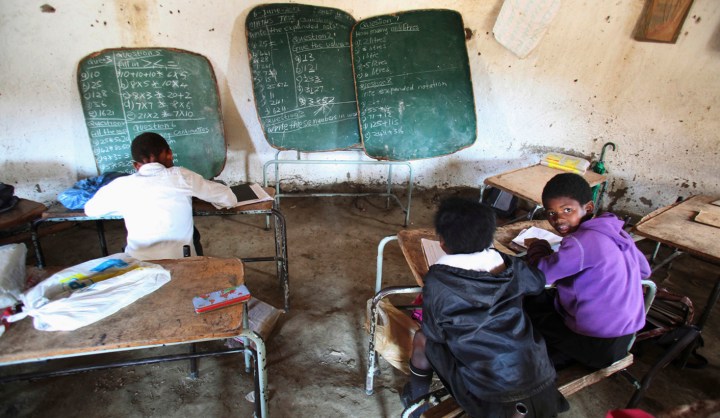

Photo: Children write notes from a makeshift blackboard at a school in Mwezeni village, Eastern Cape, in this picture taken June 5, 2012. Thousands of schools wait each year for textbooks and many children are forced to write on loose sheets, particularly in rural areas of the country. (REUTERS/Ryan Gray)

Become an Insider

Become an Insider