Maverick Life

‘Hit or be hit’: the sport where women rule the rink

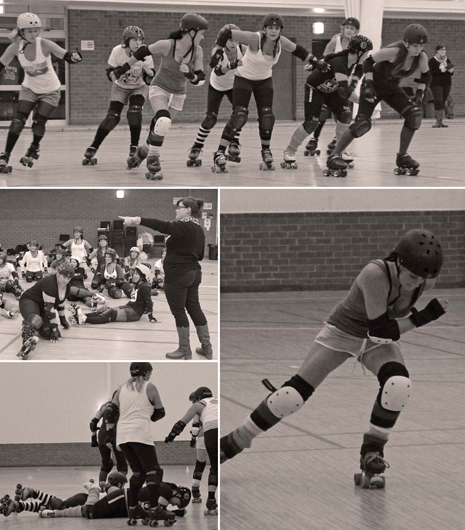

There aren’t many full-contact sports where you run an equal risk of dislocating your shoulder and suffering “fishnet burn”. REBECCA DAVIS gets introduced to the fierce world of roller derby, via Cape Town’s league of lean, mean women skaters – the Iron Meisies.

It’s a cold Monday night at a sports hall in Blouberg, and I’m watching a group of young women do things to each other that in other areas of life would earn them a police warning. They are shoving, jostling, sending each other crashing to the ground. But because they’re on wheels, it’s all okay. These are the Iron Meisies. Welcome to roller derby.

There are five women on each team, roller-skating around an oval rink. Two of them are “jammers” – the fastest skaters, the point scorers, the heroes. The other three are “blockers”, the team’s line of defence. When the first whistle blows, the blockers start skating. When the second whistle blows, the jammers set off from a line 10 metres behind. Their aim is to get past the other team’s blockers and then lap them. For every skater they pass, they get a point. The defence must stop them – which is when it gets interesting.

But let’s not get sidetracked by the details. Sure, there’s a sport here – a highly athletic sport that is under consideration for the 2020 Olympics, if it beats out wakeboarding, karate and squash, to name a few. But there is also pure rock ‘n roll: a unique kind of bad-girl pageantry accompanies the skating, involving music, outfits, outlandish personas, and a professed enthusiasm for violence. In Rollergirl: Totally True Tales from the Track, Melissa Joulwan explains: “It’s a sport of speed-skating pin-up girls and brutal body checks, played out against a backdrop of head-banging rock. The spectacle drives fans into a hormone-and-beer-induced frenzy.”

Roller derby is no fleeting trend. It’s a sport that’s been around since the mid 1930s in the US, though it started off in a different form – as long-distance endurance roller-skating marathons, which took place at indoor roller rinks. Time magazine, with evident incredulity, recorded the craze on February 3, 1936: “In 1928 it was tree-sitting. In 1930 it was dance marathons. In 1932 it was Walkathons. Last week it appeared possible than in 1936, the US appetite for preposterous endurance might take an even more eccentric form: the Roller Derby. In Chicago, 25 young men and women were roller-skating in circles around the Coliseum. They had been doing so since Christmas Day. It was the fourth Roller Derby held in the US since last August. Crowds averaged 10,000 a day.”

Surprisingly, one of the major figures in the history of roller derby’s evolution was American author Damon Runyon (whose writings provided the basis for the musical Guys and Dolls). Runyon persuaded a promoter to try turning the marathon skate races into a full-contact team sport, and roller derby was born. The biggest stars in roller derby over the 40s and 50s became household names – like Ann “Banana Nose” Calvello, also known as “The Meanest Mama on Skates”.

Calvello was as famous for her appearance – purple hair, different coloured skates, tattoos – as she was for her mean-girl tricks on the roller rink. She was notorious for beating up referees and pulling opponents down by their hair. She broke her nose 12 times in the course of a career that spanned more than 50 years. When she died, in 2006, commentator Frank Deford said: “Yeah, well, Martina Navratilova/Chris Evert is supposed to be the best female sports rivalry ever. But I never revelled in anything as much as when Calvello, skating for the bad guys, would go up against the wholesome and apple-cheeked Joanie Westin, the beloved star of the sainted Bay Bombers. My, but that was something to behold.”

With audiences dwindling in the 60s for roller derby bouts, scripted story lines were introduced, much as is the case for professional wrestling these days. Skaters staged brawls, threw pies in each other’s faces, and generally engaged in slapstick antics which failed to revitalise audience numbers. By the 70s, it looked like roller derby was dead.

It stayed dead until the early 21st century, when it was reborn in urban Texas with the help of a group of women calling themselves the Texas Rollergirls. A documentary series in 2005 helped to spread awareness of the sport, but it was 2009’s comedy-drama Whip It, directed by Drew Barrymore, which was really responsible for alerting the world to the fact that roller derby was back – and substantially more bad-ass than before.

In its current incarnation, the culture and aesthetics of roller derby borrows heavily from the Riot Grrrl punk-rock feminist movement in the mid-90s, which spawned women-fronted bands like Bikini Kill and Calamity Jane, who were in turn inspired by strong female musical figures of the 70s and 80s such as Chrissie Hynde and Patti Smith. Roller derby has borrowed the movement’s third-wave feminist philosophies – including embracing sex-positivity – but also Riot Grrrl’s DIY spirit.

The Riot Grrrls shunned major record labels, producing their own music, fanzines, performance nights, and so on; an ethos replicated within roller derby leagues today, where there are no promoters or middle-men. The skaters control all revenue. “It’s run by women, for women,” explains Iron Meisies coach Shawn Graaff, an American woman who moved to Cape Town in 2009. “The sponsorship, the infrastructure – all women.”

The Riot Grrrls spelled their name “grrrls” in order to reclaim “girls” from being used as a patronising term: they inserted a growl into the word to show the world that they weren’t to be messed with. This desire to reclaim language, which also informed the Slut Walk movement, has influenced roller derby too, where words like “bitch” and “slut” are used to bestow power rather than offence.

Teams worldwide – there are over 1,200 leagues now, with multiple teams within each – often have campy, pun-tastic names which suggest strength, violence, sex, or all of the above. New York has their Queens of Pain and Manhattan Mayhem. Other US teams include the Hell Marys, the Reservoir Dolls, and the Unholy Rollers. Johannesburg has the Thundering Hellcats and the Raging Whoremones.

Within these teams, players take on alter egos – the names by which they are known in the world of roller derby. There’s an international database of names, and each must be unique. The sources of these names are varied. Gotham Girls’ skater Ginger Snap got her name from the distinctive sound her arm made when it broke on the rink. Again, puns are big: roller girls in the US include Reyna Terror, Sybil Disobedience, Gori Amos, Miss Conduct and Helen Damnation.

Among the Iron Meisies, who total around 40 skaters at the moment, we find the likes of Sunny Slayer, Lacy Brawls, Candy Flip, Hot Rodriguez, Kaizer Woza and Dollvuis [fist]. Team co-founder Amy Olsen, who goes by the nom de skate “Fatality”, explains: “Your roller derby persona generally comes from some part of you that you want to show off.” Rollergirls author Melissa Joulwan (aka Melicious), who was a founding member of the pioneering Texas Rollergirls, sees the naming function as being aspirational: in taking on these fierce names, she writes, “We make ourselves into the girls of our dreams”.

Most roller girls have perfectly conservative day jobs. Iron Meisies Coach Graaff, 26, is an online content and social media manager. Co-founder Olsen, 27, is a communications manager. “It’s a very expressive, free sport,” says Olsen. “We have some girls on our team who are covered in tattoos. Others are moms. It attracts such a diverse group of women, but they are all women who want to be strong and really express themselves and do something, different and fun.”

“Everyone sort of has a role,” explains Graaff. “There are team moms, very much the mother hens, and there are teenage rebels, and warriors – it’s like if there was an island, like if Lord of the Flies was all women.”

That sounds very frightening. They laugh. “It is, a little bit,” says Graaff. “But we’re all still here, and we keep growing. We grow by 20% every month.”

Those are impressive figures, considering that roller derby is not a sport for the physically timid. Potential injuries range from broken coccyxes – common, Graaff says – to serious spinal cord damage. Olsen lists the safety equipment: “Wristguards, elbow guards, knee guards. Helmets – before a bout we have an officiator go round and check that the helmets fit properly.”

Graaff knows first-hand the importance of decent equipment. “When you’re moving at this pace, and you’re skating on wooden courts, and you have people wearing boots that can weigh up to five kilograms, and you get kicked in the face – I mean, I have three fake teeth. They didn’t used to mandate mouthguards.”

The rules of the sport officially prohibit contact by hands, elbows, head and feet, as well as contact above the shoulders or below mid-thigh, but that’s not to say that it doesn’t happen. In Roller Derby: The History and All-girl Revival of the Greatest Sport on Wheels (2007), Catherine Mabe records: “What may appear to an outsider as merely a hobby can actually come to fisticuffs on the track. It’s not unusual for jams to be interrupted by two skaters from opposing teams duking it out right there in the thick of it. Sometimes, in extreme cases where one skater is outnumbered by members of an opposing team, dogpiles will completely disrupt a jam, with all of the skaters foregoing point-scoring for bloodlust.”

I don’t witness any of that at the practice session on Monday evening, but I see a lot of high-speed falling. Every now and then there’s a domino effect and a whole group of them goes down like skittles. Is there ever any crying? Both Graaff and Olsen are adamant: no. Roller girls don’t cry, it seems.

At Monday’s practice, there are three men present, but only in a coaching or refereeing capacity, as is normally the case internationally. “It’s not exclusionary in the sense that we don’t want men doing it,” says Olsen. “It’s just that there are so many sports where there’s, like, soccer, and then there’s women’s soccer. This is something that’s created entirely for women.”

Down on the court, Louisa “Hot” Rodriguez is lacing up her skates. Rodriguez had 17 years of ballet behind her when she decided to give roller derby a try. “I just wanted something that would let me go fast and be violent,” she shrugs. “I work as a fashion assistant during the day. I do a lot of smiling. And then I get to come here.” DM

All photos by Jeanine Cameron

Become an Insider

Become an Insider