Business Maverick, Maverick Life, Media, World

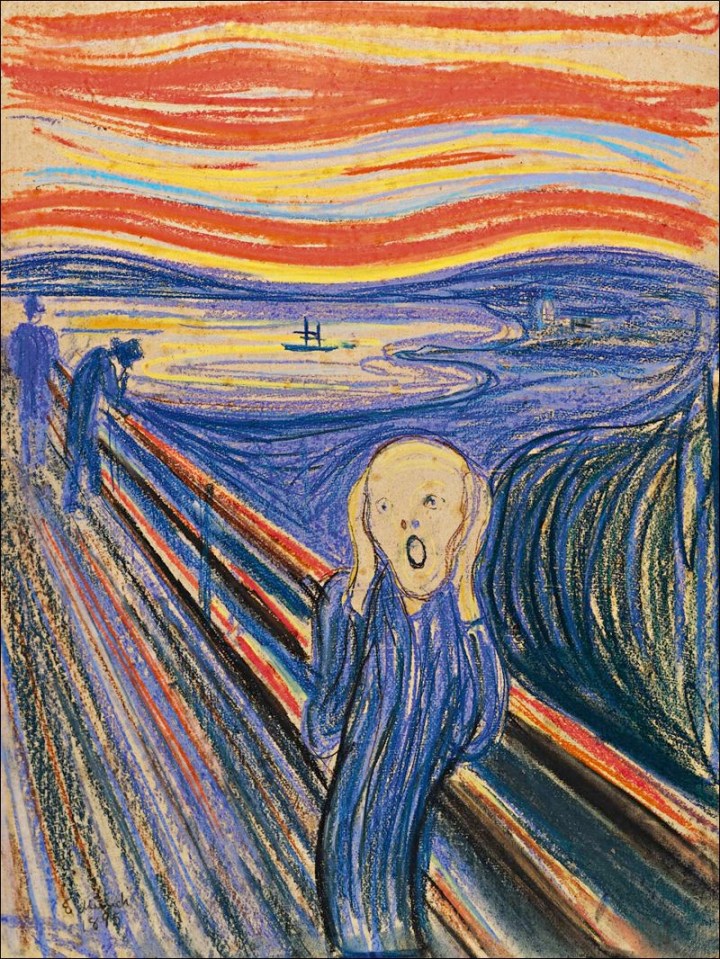

The Scream: An existential steal at $120 million

What does Edvard Munch’s most famous painting mean? Why has it just set a record for the highest price ever fetched at an art auction? The answers aren’t definite, but they have something to do with the life of the artist and the tastes of contemporary culture. By KEVIN BLOOM.

What do you see when you look closely at The Scream? The interpretation of this most famous of Edvard Munch’s works – among the most recognisable images in all of modern art – is, predictably, contested.

Critics have made (and broken) careers out of their theories on the piece, one of the tamest being that it’s a representation of that sickening feeling just before an artist breaks through chaos and hits inspiration.

A level down from that is the theory that it speaks to Nietzsche’s writings on the death of God, and perhaps the deepest level – which is more than a theory, since The Scream comes at the end of a series of paintings known as The Frieze of Life – is that the shrieking woman has passed through all the stages of the typical male-female relationship. That is, love, passion, jealousy, melancholia, anxiety and death, as captured in The Frieze’s progression. Now she is staring at the unmitigated horror of existence.

This is not, after all, a happy portrait. Still, for $22.50, from a website known as Redbubble.com, you can buy your nine-year-old daughter a Hello Kitty The Scream hoodie. From an almost countless range of online outlets, you can order your own The Scream coffee mug, with some including the added feature of the shrieking woman at the bottom of the cup (coffee break over, pal). And what’s not to love about a “Screaming Little Thinker” beanie doll for your desktop? As the brochure says, “Add a little culture and humour to your life.”

Which may be part of the reason that one of Munch’s four original versions of The Scream – the 1895 pastel on board – sold this week for $119.9 million, the highest price for an art work ever fetched at an auction.

Beating Picasso’s Nude, Green Leaves and Bust, a piece that brought $106.5 million at Christie’s in New York in 2010, it went to an unknown buyer who bid over the phone. The seller was Norwegian shipping heir and businessman Petter Olsen, whose father, according to The New York Times, was a friend and patron of the artist.

Munch, it seems, needed a patron more than most. “Though the Munchs were a prominent family of churchmen and intellectuals,” noted Mia Fineman, a curator in New York: “Edvard’s father was an impoverished army doctor whose hellfire Christianity planted the seeds of religious anxiety in young Edvard. ‘The angels of fear, sorrow and death stood by my side since the day I was born,’ he later wrote in his diary. ‘They stood by my bedside when I shut my eyes, threatening me with death, hell and eternal damnation.’ Munch’s was a haunted youth. When he was 5, his mother died of tuberculosis; his favorite sister, Sophie, succumbed when he was 14. When he was 25, his father died; soon after, his sister, Laura, went mad and was committed to an asylum.”

For the next two decades, although he would meet with increasing success, the continuation of the narrative is as unsurprising as it is morbid. The young Munch dropped out of a technical college in Norway, enrolled in the Royal School of Art and Design of Christiania, and a few years later, as a young painter, came under the orbit of the nihilist Hans Jaeger, who saw suicide as a way for a man to achieve ultimate freedom.

There was the obligatory love affair involving a shooting incident, much brawling and public drunkenness, severe bouts of anxiety and depression, and, in 1908, the unavoidable nervous breakdown.

But against all odds, Munch would go on to live the second half of his long life in peace and tranquility. He followed the advice of his doctors and drank less, and instead of dwelling in the darkness of his own soul he chose as subjects for his paintings some of Oslo’s wealthiest men (which earned him good money), scenes of farm life, and naked females. He died in his bed soon after his 80th birthday.

It was The Scream, though, that earned the Norwegian his place among the great artists of the 20th century. An entry from his diary in 1892, a year before he completed the first of the four versions, contains the following immortal lines: “I was walking along a path with two friends – the sun was setting – suddenly the sky turned blood red – I paused, feeling exhausted, and leaned on the fence – there was blood and tongues of fire above the blue-black fjord and the city – my friends walked on, and I stood there trembling with anxiety – and I sensed an infinite scream passing through nature.”

These were also the words hand-painted by Munch in poem form on the frame of the 1895 version, the pastel-on-board rendition that has just sold for $120-million. So what does the painting really mean and why is modern humanity so drawn to it? The answers are as many as there are people with troubled souls. Still, isn’t it slightly ironic that a representation of 19th century psychic angst, an artwork so visceral that it cuts to the core of what it means to silently suffer, has been taken up by the early 21st?

As Peter Aspden, arts editor of the Financial Times, noted recently: “Someone, somewhere in the world is busy planning to pop this icon of human disintegration above the fireplace, at enormous cost. We are, it seems, past the age of water lilies and sunflowers.” DM

Read more:

- So, what does ‘The Scream’ mean?, in the Financial Times.

Photo: Edvard Munch’s The Scream.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider