“The Guardian is a very different kind of beast from other papers,” Alan Rusbridger told New York Magazine’s Steve Fishman as they strolled through The Guardian’s Euro-chic looking US offices. “It’s always been an outsider. It’s never been in the club. Which is why I think it’s not an accident that The Guardian ended up doing the phone-hacking story. It took an outsider to see that this was a story, and to do it.”

And it is unlikely that Rusbridger would be part of any old-style press cabal. As The Atlantic puts it: “he broke the unwritten gentlemen's agreement that newspapers don't criticize the behaviour of rival newspapers, that you don't ‘piss on your own’, as one journalist put it.”

There was a time when few people outside of Britain knew who Rusbridger was, but following the closure of News of the World and News Corp’s public fall from “grace”, the editor of The Guardian is the media man to interview. The reason why everyone wants Rusbridger’s next erudite sound bite is because, as AdWeek states, his “paper may well have brought down, virtually single-handedly, not just a media giant but an entire government”.

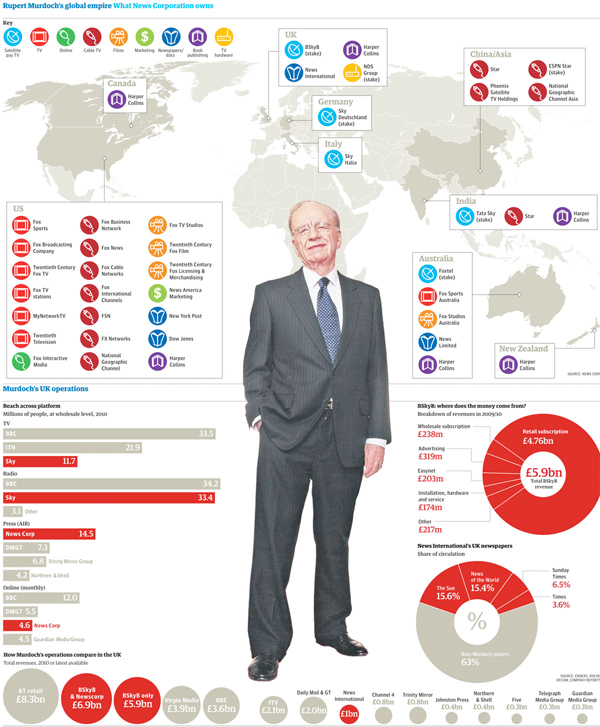

Photo: The Guardian's infographic depicting Murdoch's global media interests.

And the man who had the balls to take on Murdoch is right, The Guardian couldn’t be more different from those conquistadorian colonists he took out at the knees. Rupert Murdoch is the Alexander the Great of the media who sought to create a media legacy in News Corp that would reach the "ends of the world and the Great Outer Sea". Murdoch the conqueror, not satisfied with owning Australia, in 1973 invaded the United States with the acquisition of the San Antonio Express-News.

Acquisitions followed thick and fast and included the New York Post, as well as half and then the whole of 20th Century Fox. In the mid-1980s Murdoch would become a US citizen and, in the next decade, acquired that Republican-friendly channels known as Fox News.

Despite Fox News' ideological allegiance, Murdoch isn’t faithful to any ideology. As Russ Baker said in the Colombia Journalism Review, Murdoch “moves effortlessly between Republicans and Democrats, Tories and Labourites, capitalists and communists, depending on what deals are cooking.” The raison d’être of Murdoch and News Corp (who are one and the same) has always been growth, money and power.

The paper Rusbridger edits couldn’t be more different. The Guardian’s genesis was the UK Massacre of Peterloo which followed the Napoleonic Wars. Amid chronic unemployment and widespread famine, the British parliament introduced protectionist corn laws which outlawed the import of cheaper staples offshore.

In 1819, tens of thousands of people gathered at St Peter's Field in Manchester to protest and to demand parliamentary reform, but local magistrates called in the military who charged on the civilians with swords drawn. Fifteen were killed and another 700 injured.

A group of businessmen who witnessed the massacre formed a non-conformist liberal group called The Little Circle to fund the establishment of a newspaper to fight for social reform. All the members of The Little Circle would write for this paper, which would later be known as The Guardian, in part to advance their liberalist agenda.

The newspaper would make significant strides and go national under the editorship of C P Scott, editor for 57 years from 1872. Scott bought the paper in 1907 and declared that it would serve a higher purpose, rather than merely turning profit.

“It is much more than a business; it is an institution; it reflects and it influences the life of a whole community; it may affect even wider destinies,” wrote Scott to celebrate his 50th year as editor, and the centenary of the paper that was now called The Guardian.

“It is, in its way, an instrument of government. It plays on the minds and consciences of men. It may educate, stimulate, assist, or it may do the opposite. It has, therefore, a moral as well as a material existence, and its character and influence are in the main determined by the balance of these two forces. It may make profit or power its first object, or it may conceive itself as fulfilling a higher and more exacting function.”

An important change in ownership happened in 1936, when the paper was acquired by the Scott Trust, established to protect future owners of The Guardian from meddling with the paper’s liberal editorial position. The trust would ensure that the paper would remain true to the benevolent intent of its founders and to Scott’s vision.

Unlike other newspapers where the profits are sucked out of the operations by shareholders, the owners of The Guardian reinvest profits to “sustain journalism that is free from commercial or political interference” and to uphold the paper’s original values. These values include the intent that the paper should enjoy “a moral as well as a material existence”, that “the voice of opponents no less than that of friends has a right to be heard” and that “comment is free, but facts are sacred”.

It is in this tradition that The Guardian has waded into the digital age with a commitment to opening its journalism to the public it serves, rather than putting up walls. "Open is our ‘operating system’, a way of doing things that is based on a belief in the open exchange of information, ideas and opinions and its power to bring about change," said Rusbridger in an editorial explaining the thinking behind the media brand’s public move to everything open.

Photo: The Guardian's Open Journalism initiative.

The Guardian has long been known and respected for embracing the Internet and making digital a part of its very DNA, but it nailed its colours to the mast with a major campaign to showcase its open journalism and multi-platform credentials. The campaign includes The Guardian’s view of what open journalism looks like in the retelling of that familiar fairy tale The Three Little Pigs. The ad shows how the digital age has changed everything and how The Guardian has opened its platforms to give readers what they say is the “whole picture” of news.

"The Guardian has championed digital innovation and a unique, open model of journalism," Rusbridger said, introducing the campaign. “There’s a break now between the 19th and 20th century idea of a journalist and a journalist today, and you see it on Twitter, you see it in the acknowledgement of the way information is now parcelled up, moved around, shared; the way people are using links, directing people, replying, taking part in journalism rather than being passive recipients of journalism. That’s a mind-set that says journalists are not the only experts in the world,” he elaborated in an interview on Guardian.co.uk.

The Guardian’s commitment to open journalism is ground-breaking and profound. In throwing its doors open, it becomes the biggest working model of how a medium unencumbered by commercial or partisan interests can use the Internet in partnership with its readers and the British electorate to be a true “Fourth Estate”. It is the real experiment of how digital tools, data, the public and sound editorial intent can work together for the common good.

For Rusbridger and his team, open journalism is more than a mantra or a metaphor, but a lived reality. Over 5,000 readers visited The Guardian’s offices in late March as part of the paper’s first open weekend. For those unable to hear Rusbridger speak to them directly, the Internet provided an opportunity to ask the editor directly what open journalism was all about.

“Open journalism is journalism which is fully knitted into the web of information that exists in the world today,” Rusbridger responded to one reader’s query. “It links to it; sifts and filters it; collaborates with it and generally uses the ability of anyone to publish and share material to give a better account of the world.”

The Guardian has thought up 10 guiding principles for the practice of open reporting, which reads much like Cluetrain meets journalism. The principles talk about dissolving the "us vs them" divide, forging collaboration, surrendering control, involvement in all the stages of journalism, transparency and acknowledgement that journalists aren’t the only experts – that readers are equally important.

It’s a smart strategy because readers will become increasingly important in The Guardian’s future. Guardian Media Group plc (GMG) lost £54.5 million during its last financial year, marginally more than 2010’s £53.9 million. Subsidised by the non-profit trust, GMG had £577.5 million in investments in 2008. By 2011 that had been whittled away to £197.4 million.

Rusbridger might have levelled Murdoch and made journalism history with Wikileaks, but if he doesn’t contain the losses and increase the revenues, The Guardian may well run out of funds.

During March’s open journalism weekend he asked readers what value they’d trade for the media brand – data, time or money. The Guardian hasn’t ruled out a paid subscription model, but Rusbridger says that’s not on the cards just yet. And as he looks for solutions to boost revenue, Google has come up with an interesting new option: a joint venture of sorts with news publishers, where Google runs surveys that form the reader’s “payment” for reading a free article. Readers get to fill in research and read for free, and the new site gets a micro-payment for each survey that’s completed by a reader.

During the open weekend Rusbridger said “There are clearly dangers in over-dependence on advertising, but, broadly I think it's been a beneficial factor in newspaper publishing over the centuries... and will continue to be.”

While advertising remains key to The Guardian’s future survival, finding new revenues through open journalism so that it can continue being a benevolent social force is as important. As the guardian for the good, Rusbridger’s press plays a crucial role in not only policing government and industry, but other media as well. Long may it continue to do so. DM

This is part two of a three part series. Read the first instalment about the Los Angeles Times – a press that merely serves shareholder returns. The next instalment will focus on the future of journalism.

Read more:

- The Atlantic: How Britain's Guardian Is Making Journalism History.

- Google launches revenue-generating surveys in Journalism.co.uk.

- 63 Minutes With Alan Rusbridger in New York Magazine.

- Open Journalism at The Guardian.

- Watch Alan Rusbridger talk about open journalism at The Guardian.

Photo: Alan Rusbridger, the editor of the Guardian arrives to give evidence at the Leveson Inquiry into the culture, practices and ethics of the media, at the High Court in central London, on 17 January 2012. REUTERS/Andrew Winning.