Business Maverick, Maverick Life, Media, World

The Future Eaters… effectively beyond parody

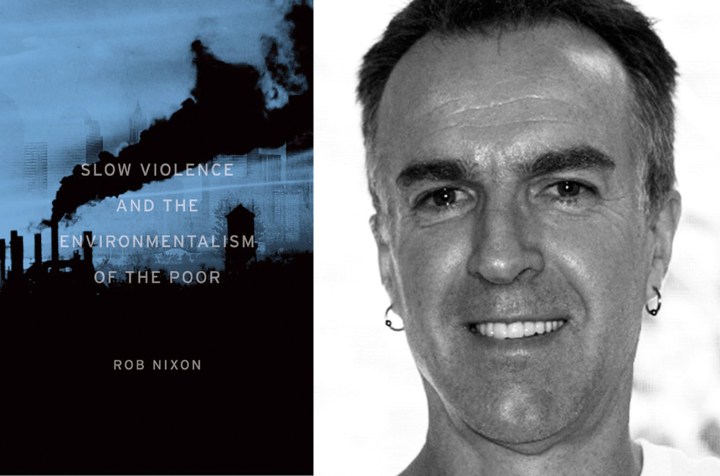

In Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor (Harvard University Press, 2011), Rob Nixon performs a dense but stylish call to activism, writes HEDLEY TWIDLE.

The 17th Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (mercifully shortened to COP17), which was recently held in Durban, seemed to pose something of a challenge for journalists. Much newsprint space was set aside in advance for supplements and special reports, but when the time came it seemed that those covering the event were casting about a little, struggling to make the gathering and all it meant (or didn’t mean) writeable and readable.

Eventually, at the eleventh hour, a “narrative” of sorts offered itself, or was concocted: South African foreign minister Maite Nkoana-Mashabane drew certain fractious nations into a dignified huddle in the early hours and salvaged… well, not a deal, but a “platform” promising “a legal instrument or an agreed outcome with legal force” (next time around) and the possibility of a deal, somewhere, somehow (next time around)…

Like the many environmental crises of which it is the godfather, climate change is very difficult to write about: to represent, in the fullest sense. It eludes our ready-made narratives for disaster. Schooled by blockbusters into expecting either apocalypse (The Road) or last-minute, plucky rescue (nuclear fission, Matt Damon), much of the online audience surely tends to switch off, or click away, at the first mention of another climate change summit.

It conjures images of unilateral people (with lanyards) fussing for weeks over the wording of a paragraph, as if possessed of child-like belief that the vagaries of the planet’s atmosphere will somehow correspond to their wording, obey their diktats.

As global warming meets global apartheid, it becomes an ever more lethal cocktail of stark simplicity and ferocious complexity: the relentless upward graph of CO2ppm in the atmosphere combined with the convoluted, uneven way it poisons the biosphere, most affecting those who are least visible, and least responsible.

It is a complexity, and a representational challenge, that has allowed those with vested interests and deep pockets to stall, obfuscate and greenwash for many years. One of the most galling things of the last decades has been watching the lexicon of social justice (and even critical theory) being co-opted by right-wing think-tanks and hyper-capitalist quangos. When a Bush-era report suggests that anthropogenic climate change is only one “narrative” among others; when Big Oil begins talking about historical carbon emissions and telling us that developing nations must be allowed to industrialise, one has the sense that progressive lines of argument have been hijacked by reactionary, market-driven forces committed to the status quo. As with those young (white) South African men who persist in having late middle-aged (black) women cleaning up after them because it creates employment, one enters a zone where self-interest, redistributive ethics and a relentlessly economistic vocabulary become increasingly confused and contaminated by each other.

It is such challenges – of giving dramatic visibility to the complex politics and “attritional lethality” of environmental crises – that Rob Nixon addresses in his recent book Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor. In a work of (the cliché really is applicable) remarkable scope, he examines the political strategies and rhetorical tactics of environmentalists and writer-activists from the developing world, among them Wangari Maathai, Ken Saro-Wiwa and Arundhati Roy, as well as figures who are less well known in the anglophone world: Indra Sinha, Abdelrahman Munif and Adriana Petryna.

In each chapter, a crisis is married to a literary genre: Bhopal and its aftermath are explored through the “environmental picaresque” of Sinha’s Animal’s People (2007); US petro-imperialism in the Gulf is seen through the lens of Munif’s novel cycle, Cities of Salt (1984); Saro-Wiwa’s and Maathai’s protests against oil drilling and deforestation respectively are considered in terms of the “movement memoir” and its difficulties – how an autobiographical text is also required to function as the “biography” of a social collective.

As the second half of the book’s title suggests, these examples are intended to bury forever the idea that environmentalism is the preserve of middle-class Westerners (another apparently “radical” position that, I have always thought, often camouflages a reactionary stance – at least when voiced by middle-class Westerners). Yet at the same time, Nixon’s book is alert throughout to the uneasy relationship between environmentalist and postcolonial methodologies, particularly as they have evolved in the Anglo-American academy.

One of the main charges Nixon levels against American environmentalism is that it has remained scandalously parochial: obsessed with discussing and deconstructing images of the wild (or not-so wild) West while remaining almost entirely un-engaged with the long-term consequences of American foreign policy: the “offshore histories” of nuclear testing in the Pacific, Agent Orange in Vietnam, depleted uranium in Iraq. The troops have now gone home, but the toxic particles they left behind, blowing from spent shells and burnt-out tanks, have a half-life of 4.51 billion years. That’s slow violence.

So how can writers plot and give figurative shape to “formless threats whose fatal repercussions are dispersed across space and time”, the “long dyings” and “disasters that are anonymous and star nobody”?

In South Africa, one can think of the difference between rhino poaching and acid mine drainage, or fracking. The first is spectacular, gory, shocking to game-reserve-goers, easily blamed on people over there. The latter are subterranean, invisible, incremental, capillary – they blur the lines between colonial dispossession and national self-determination, between natural and human ecologies.

How, asks Nixon, have writer-activists tried to make real these “calamities that patiently dispense their devastation while remaining outside our flickering attention spans – and outside the purview of a spectacle driven corporate media”?

Writing post-Deepwater Horizon but pre-Arab Spring, he asks: what chances for digital activism when the electronic screen has itself become “an ecosystem of interruption technologies”?

Shuttling between vast planetary timescales and close textual analysis, the result is a genre-defying book that is by turns an exercise in comparative reading; an enquiry into the modes and possibilities of contemporary non-fiction; a series of case-studies on the most inspiring public intellectuals of our time; a short history of the American imperium; a call to activism. It is dense but always stylish, and (as Frantz Fanon called for) passionate scholarship.

It is, in fact, an academic page-turner (that rare thing), and one that would surely have earned the admiration of the author’s one-time teacher and mentor at Columbia, Edward Said, whose crisp, critical prose is set against the turbo-capitalist, financially deregulated lingo of one Lawrence Summers. Consider this little nugget, used as epigraph for the first chapter. It comes from a leaked memo by Summers of 12 December 1991, when he was Chief Economist of the World Bank:

“I think the economic logic behind dumping a load of toxic waste in the lowest wage country is impeccable and we should face up to that… I’ve always thought that under-populated countries in Africa are vastly UNDER-polluted, their air quality is probably vastly inefficiently low compared to Los Angeles or Mexico City… Just between you and me, shouldn’t the World Bank be encouraging MORE migration of the dirty industries to the LDCs [Least Developed Countries]?”

Utterly technocratic, effortlessly managerial, totally “logical” – it is a language that is effectively beyond parody. And it’s worth remembering that Larry Summers, having presided over the 2008 crash, was then appointed to the White House National Economic Council in 1999, becoming one of Barack Obama’s key advisers.

As The Social Network reminds us, Summners was also once President of Harvard University, the institution now publishing this book. All of which leaves one with the anxiety that the 21st-century university might just be letting an academic or two blow off some steam, with no threat to business as usual.

Against this, however, we can set the likes of Rachel Carson and Arundhati Roy, both of whom write polemically, brilliantly and influentially against a world in which only a handful of (male) “experts” are qualified to pronounce on matters that affect millions of people (India’s megadams alone have displaced perhaps 60 million…).

Taking aim at the World Bank feasibility study or the environmental impact report – its ponderous diction, tone and length, its strategically passive voice – Roy deployed the personal essay. As a “small, nimble form”, it “allowed her to take on the weighty, leaden genres that gave ballast to the culture of the megadam and, beyond that, to the culture of developmental gigantism”.

Her prime contribution as a writer-activist, Nixon suggests, was “to expose the insidious, traumatic violence inflicted on the most vulnerable, human and nonhuman, by the affectless language of technospeak”. In Power Politics (2001) she writes memorably of visiting a conference on water privatisation:

Language is the skin of my thought… At the Hague I stumbled on a denomination, a sub-world, whose life’s endeavour was the opposite of mine. For them the whole purpose of language is to mask intent… They breed and prosper in the space that lies between what they say and what they sell.

In moving beyond the emotionally miniaturist tradition of the English essay – while still harnessing its lyrical and personal qualities for polemical force – she joins (in one of Nixon’s idiosyncratic, international genealogies) the very different figures of Edward “Monkey Wrench Gang” Abbey (inspiration for eco-saboteur groups like Earth First!) and Jamaica Kincaid, whose 1988 memoir A Small Place remains one of the most scorching indictments of the leisure tourist industry ever written.

Perhaps the most intriguing demonstration of Nixon’s contrapuntal, mixed-genre approach is the chapter on South African game parks. It is essential reading for anyone who has felt that there is something deeply suspect about these hallowed national spaces. Or to put this in more scholarly terms: that South Africa is a site where “the segregations of humans from non-humans have long been implicated in the violent segregations of humans from humans”. That is to say, across much of Southern and East Africa, “game” reserves and “native” reserves “have shadowed each other historically in the interdependent administrations of conservation, leisure and labour”.

The contrast that the whole book turns on – between the spectacular and the everyday – may well have already called to mind the work of Njabulo Ndebele. In this chapter, we see his uneasy account of visiting a game park as a (black) tourist read alongside three other journeys: Nixon’s own, Gonzo-esque account of visiting a canned lion hunting reserve in the Eastern Cape in 1994, where he meets the owner J P Kleinhans (subsequently mauled to death) and his son, Adolf; James Baldwin’s classic essay Stranger in the Village; as well as Gordimer’s The Ultimate Safari, where the protagonists are not leisured tourists but migrants and border-jumpers, struggling to exist in the harsh environment of the Kruger Park beyond the “rest camps”.

Nixon develops a reading of the contemporary South African game reserve as a deeply paradoxical space: one which capitalises on the expanded, globalised tourist industry enabled by the “new” political dispensation, while simultaneously reinstating a “timeless” Africa that is racially exclusive and possibly hostile to social transformation. As such, it risks becoming (and I wanted to give a cheer of recognition at this point) a site where “a provincial whiteness is fortified by white pilgrims from abroad”. Yet at the same time, he asks how such spaces might be repossessed, imaginatively and experientially, within a shared, post-apartheid imaginary.

The last question signals how this is a book that is not content to remain within the predictable shapes of postcolonial critique. Rather, it carries a sense of taking debates in the environmental humanities in new and energised directions, pushing at the boundaries of existing models. Over the last years, having tried to work towards a less compromised way of imagining the relation between natural and social histories in southern Africa, I have often found myself thinking back to the last lines of E. M. Forster’s A Passage to India – “Not here, not yet”. Nixon’s work leads me to return instead to the incomparable Roy, as she balances the constant threat of rhetorical exhaustion with the need to keep writing, and fighting. Even if there is nothing new or original left to be said about nuclear weapons, or deforestation, or climate change:

…Let’s pick our parts, put on these discarded costumes and speak our second-hand lines in this sad second-hand play. But let’s not forget that the stakes we’re playing for are huge. Our fatigue and our shame could mean the end of us. DM

© Stellenbosch Literary Project (SLiP), Department of English, Stellenbosch University. For other literary reviews, reports, blogs, translation and events, see www.slipnet.co.za.

ALSO on SLiPNET:

- Who are the Hottentot Trio and how does their music sound? See edited videos of the polished/rough performance ethic of Cape artists riding the edge in SLiP’s InZync Poetry Sessions.

- Join writer-at-large and poet Finuala Dowling in an online poetry workshop. The challenge, as the centenary of the Titanic’s sinking is observed, is to capture the feel of disaster in current times.

- What were Antjie Krog, Mongane Wally Serote, Leon de Kock and other writers up to at the recent Woordfees festival?

- Taste a sample of new literary translation in progress of works by Mongane Wally Serote, Etienne Leroux and Ingrid Winterbach.

Photo: Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor by Rob Nixon.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider