Maverick Life, Media, World

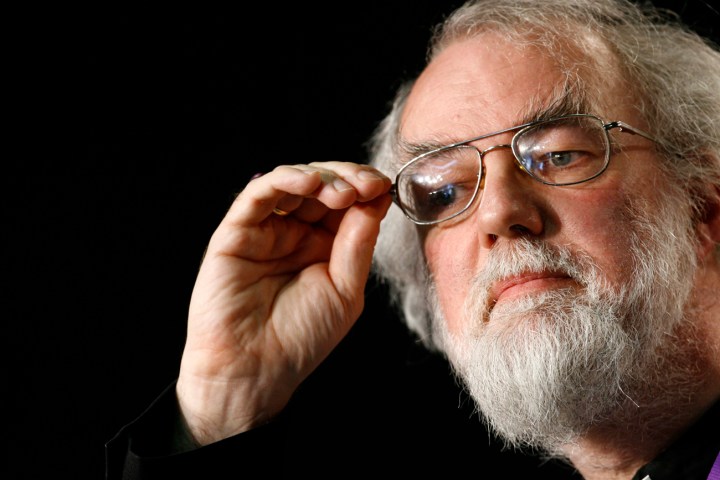

Soon to be former Archbishop of Canterbury, the philosopher priest, the man

The current head of the Anglican Church, Rowan Williams, has announced that he will step down from his position at the end of the year. REBECCA DAVIS examines his nine years of tumultuous leadership.

It is said that the 104th Archbishop of Canterbury never wanted the job. From the other side, many people didn’t want Rowan Williams in the job either. The self-described “bearded leftie” was seen more as an academic than a clergyman: too clever, too liberal, and too Welsh. Williams was Archbishop of Wales before being appointed to the top job in the Church of England, and since he announced his resignation last Friday, retrospective criticisms of his time in the post have suggested that he never quite acknowledged the significance of his position in English history and culture.

The position of Archbishop of Canterbury is indeed a daunting one. The Primate of All England’s social position is ranked lower only than the members of the Royal Family. As the head of the Anglican Church he must lead the “Anglican Communion”, the international association of Anglican churches, with a membership of around 80-million worldwide – an estimated three-quarters of which live in Africa. In addition to his religious duties, he is also expected to play an active role in public life in the UK, providing a kind of moral compass for the nation and responding to political developments where appropriate.

Rowan Williams was enthroned as Archbishop despite reservations (including his own) because he was reportedly head and shoulders above the other candidates. Even his most staunch detractors could not dispute the fact that Williams is a brilliant mind. He gained his doctorate in theology from Oxford and worked as an academic thereafter, only becoming Bishop of Monmouth in 1992 and Archbishop of Wales in 1999. Williams was not a “career clergyman”, therefore he cut his teeth in the lecture hall rather than the pulpit.

There were other reasons why Williams made an unlikely head of the Anglican Church. He had been arrested while on an anti-nuclear demonstration in the 1980s. He had written a defence of gay relationships, The Body’s Grace, in 1989. He is a poet who chafes against the idea that he might be a “religious poet”: he prefers to describe himself as “a poet for whom religious things mattered intensely”. Williams is a passionate admirer of Russian novelist Fyodor Dostoevsky, described by philosopher Walter Kaufmann as “a rabid anti-Semite, anti-Catholic, and anti-Western Russian nationalist”. Williams learned Russian so he could read Dostoevsky in the original. In total, he speaks five languages and reads six more. One of Williams’ children was once heard boasting that their father was the cleverest man in Europe. Hyperbole, maybe, but there is no disputing his intellect.

Williams could not have become Archbishop at a less auspicious point in the history of the Anglican Church, at least since the split with Rome during the reign of Henry VIII. The two issues which would come to dominate the last decade in Anglican circles, and which would thus dominate his leadership, were those relating to gays and women. Williams was known to be liberal on both issues when he took up his post. His predecessor, George Carey, had maintained a blacklist of clergy who would never become bishops. One of Williams’ first acts as Archbishop was to remove the name of Jeffrey John from that list. John, a long-time friend of Williams, was an openly gay senior cleric. We’ll return to John in a moment, since in some ways the controversy around him sums up the central tensions of Williams’ stint as Archbishop. But to shed some light on Williams’ views about gay relationships, it may be instructive to consider his 1989 essay on the matter, The Body’s Grace.

The Body’s Grace is worth reading in full, since apart from anything else it’s a very elegant and eloquent piece of scholarship. But it is also an extraordinary work when you consider that it was authored by the current Archbishop of Canterbury because it is so forthright, even radical, in its views on human sexuality.

“Most people know that sexual intimacy is in some ways quite frightening for them; most know that it is quite simply the place where they begin to be taught whatever maturity they have,” Williams begins. “Most of us know that the whole business is irredeemably comic, surrounded by so many odd chances and so many opportunities for making a fool of yourself; plenty know that it is the place where they are liable to be most profoundly damaged or helpless.”

Photo: Britain’s Queen Elizabeth, departs Lambeth Palace with Prince Philip, Archbishop of Canterbury Rowan Williams and his wife Jane in central London on 15 February 2012. They were attending a Diamond Jubilee multi-faith reception. REUTERS/Toby Melville.

Drawing on the work of philosopher Thomas Nagel, Williams notes that there are sexual encounters which “have some claim to be perverse” because there is such an imbalance in power relations between the two participants (like rape, paedophilia, or bestiality) that one person “doesn’t have to wait upon the desire of the other”. Williams suggests parenthetically here: “Incidentally, if this suggests that, in a great many cultural settings, the socially licensed norm of heterosexual intercourse is a “perversion” – well, that is a perfectly serious suggestion…” Note that this is not a moral pronouncement – Williams is here daringly playing around with the work of another philosopher. But it’s the kind of game that is routine for academics, but from church leaders (although Williams was yet to be one when he wrote this) it seems downright revolutionary.

Williams suggests that married sex has a handy “justification” in that it lends itself to the goal of producing children. “Same-sex love annoyingly poses the question of what the meaning of desire is in itself, not considered as instrumental to some other process (the peopling of the world)”, Williams muses. But what if God did not consider sex as purely functional, Williams asks – and points to the existence of the clitoris in women. “If God made us for joy…?”

Part of the reason for “the massive culture and religious anxiety about same-sex relationships”, Williams sums up, might be due to “the fact that same-sex relations oblige us to think directly about bodiliness and sexuality in a way that socially and religiously sanctioned heterosexual unions don’t”. He ends by calling for “a theology of the body’s grace which can do justice to the experience, the pain and the variety of concrete sexual discovery”.

It’s pretty heady stuff, and it firmly establishes Williams’ idea that there’s no necessary contradiction between homosexuality and religious faith. And it was presumably drawing on these kinds of ideals that led Williams to champion his gay friend Jeffrey John’s appointment as Bishop of Reading in May 2003, shortly after Williams took his post. John had a long-term relationship with another Anglican priest, but they openly stated that their relationship was celibate. In the two months after John’s appointment was announced, war raged in the Anglican Church. Conservative Anglican leaders expressed their outrage with John’s appointment and the fact that he had failed to publicly “repent” for his past sexual activities. A number of leaders threatened to split from the Anglican Communion. The new Archbishop of Canterbury, having stepped straight into this raging controversy, backed down and pressured John to step down from his nomination. John had no choice but to comply.

The episode was troubling for those who hoped that Williams would be able to carry some of his deeply felt personal convictions through to his church position. But what was Williams to do? This was the central conflict of his tenure. In holding to his belief that the most important thing was that the Anglican Communion must stay together no matter what, Williams was forced to sacrifice his belief that gay people and women had the right to become ordained as bishops in the Anglican Church. Writing for the Guardian after Williams’ resignation, Giles Fraser (former Canon Chancellor of St Paul’s Cathedral, who stepped down in protest over the handling of the Occupy London movement) said: “In effect, he became a split personality – with Williams the man at odds with Williams the archbishop”.

The problem is that Williams has always been too liberal for the conservatives and too conservative for the liberals. Despite giving way on gays and women, he has nailed his colours to the liberal flag in different ways over the past years. Williams signed a petition against the Iraq War in 2002 and wrote to Tony Blair in 2004 to criticise the alleged abuse of Iraqi detainees. In 2007 he called a UK strike against Iran or Syria “criminal, ignorant and potentially murderous folly”. He caused a storm in 2008 by suggesting that Islamic sharia law had a potential role to play in British law in settling some disputes. (The subsequent outcry conveniently ignored the fact that some sharia principles are already in effect.)

In 2011 he issued a fairly outspoken critique of the Tory coalition government in the UK when he guest-edited an issue of the liberal New Statesman magazine. He wrote in it that the Tory government was committing Britain to “radical, long-term policies for which no-one voted”. He also criticised the absence of “real argument about shared needs and hopes and real generosity”. Prime Minister David Cameron’s response was that he “profoundly disagreed”. It wasn’t the first time that the two have butted heads – there are rumours that Williams became increasingly cheesed off with Cameron for repeatedly cancelling meetings with him last-minute. Nonetheless, Cameron gave a generous response to the news of Williams’ resignation, calling him “a man of great learning and humility”.

In religious terms, too, Williams has been accused of peddling a kind of Christianity-lite which is out of pace with, in particular, the increasingly conservative African Anglican groups who hold a lot of sway over the Anglican Communion. He has said, for instance, that he does not believe that creationism should be taught alongside evolution in schools. In February he participated in a public debate with arch-secularist Richard Dawkins at the Oxford Union, an encounter which had been billed as the ultimate showdown between religion and science but which emerged as more of a whimper than a bang. Did Williams believe that the theory of evolution was correct and humans had a non-human ancestor, Dawkins asked. “Most likely,” said the Archbishop. Then what was the book of Genesis about? Williams explained that these were “not literal narratives, but stories with deeper truths about the nature of humanity and the creator”. Dawkins hit him with the age-old question: why would a caring God not put an end to suffering? “I find that very difficult,” Williams said. “If He can do that, why doesn’t He do it a bit more?”

Such forthright answers may be deeply refreshing to people who believe that this is the kind of path the Church needs to traverse in future to win over increasingly agnostic populations, but they are unlikely to win him many fans in the more conservative sectors of the Anglican Communion. In the face of such rapidly divergent elements of his church, the best Williams was able to do to try to stop the church splitting altogether was to propose an “Anglican Covenant”. His plan here was that the church’s separate provinces would be unable to take independent action on issues like the ordination of women without a broader consensus from the rest of the church. A number of conservative parishes have supported this measure (particularly in Africa and Asia) but it looks almost certain to fail: so far 17 English dioceses have rejected it, with only 10 in favour.

Williams knows it is likely to fail, and this is probably a major motivation in his resignation now. It is really hard to see what his successor is going to do differently in order to succeed where Williams has failed, though, which is why the position is now even less enticing. Williams told the BBC: “I would hope that my successor has the constitution of an ox and the skin of a rhinoceros, really”.

The two frontrunners for the job are the current Archbishop of York, Nigerian John Sentamu, and the Bishop of London, Richard Chartres. English bookies are currently giving Sentamu the most favourable odds. Whoever succeeds to the position will almost certainly try a more conservative path than Williams, but will equally almost certainly preside over a schism in the Anglican church, which now seems almost guaranteed.

As for Williams, he of the unruly eyebrows and untidy beard, he will take up a position back within the safety of academia at Cambridge next year. No doubt it will be something of a relief. He leaves an uncertain legacy, but at least one man is confident that nobody could have done the job better. Desmond Tutu said in response to Williams’ resignation that he was “the best gift God could have given to the Anglican Communion. His intellect, his spirituality and prayerfulness have held a fractious communion together. With anyone else less gifted we would have torn ourselves apart.” Clever man, our Arch is. DM

Read more:

- Archbishop of Canterbury Rowan Williams to stand down, in the BBC.

Photo: Archbishop of Canterbury Rowan Williams gestures as he listens to a question during a news conference. REUTERS/Andrew Winning.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider