Sci-Tech

The curious case of the ‘Curie complex’ and gender bias in science

The charge that science is an inherently sexist discipline is repeated so often it’s a cliché. American historian and author of The Madam Curie Complex, Julies Des Jardins throws a spanner in the works by saying that women often limit themselves. Isn’t it time to debunk the “science” of gender discrimination in science? By MANDY DE WAAL.

The 27th president of Harvard was in a provocative mood when he stood up to talk about gender bias at a conference on diversity in America’s science and engineering workforce.

It was 2005, and Lawrence Summers, the illustrious economist who was once Clinton’s secretary of the treasury, was talking about the underrepresentation of women in science, when he suggested something unfortunate that proved career–limiting.

Summers hypothesised that one reason that there were fewer women in top jobs in maths, science and engineering in the US was because of innate differences between the sexes. The feminists whipped out their arsenal, and even though there were pockets of people at Harvard who thought their president a brutal, blunt but brilliant administrator, it wasn’t enough to save him. Despite three apologies, Summers received a vote of no confidence and was ousted from the university because of his “big mouth”. (In 2009, he became head of President Obama’s White House National Economic Council.)

But it was Summers’ “big mouth” that would start historian Julie Des Jardins thinking about women in science, and eventually prove the impetus for her writing The Marie Curie Complex: The Hidden History of Women in Science. “People were so angry, and as a cultural historian I was interested in what the charged nature of what he had said was. I wondered what it was that he tapped into,” says Des Jardins, speaking to iMaverick from New York.

Des Jardins became convinced that the problem of women in science was predominantly cultural and this Associate Professor of Modern American History, Gender and American Women at Baruch College decided to write a cultural history of science in the 20th century.

Now, if you’re going to write about women and science in the 20th century, you can’t do this without reflecting on Marie Sklodowska Curie, who’s too often revered as the “Mother of Modern Physics”. The mother epithet is hardly a compliment, but let’s wait for Des Jardins to explain why the “mother” metaphor has been such an albatross for women in science, a little later in this piece.

Of Curie Des Jardins says: “If you ask people to name a female scientist she would probably be the one and only women scientist that comes to mind.” Curie and science go together in much the same way two hydrogen atoms stick with an atom of oxygen in a molecule of water.

The Polish-French scientist travelled to the US in the 1920s in the hope she’d become a cause célèbre for women in science. Des Jardins says this landmark journey provided the perfect mirror for examining the cultural messages that Americans (if not all people) formed and still form about female scientists. “You can see these attitudes by looking at how Madame Curie is thought of and written about. She is this lens through which Americans see women, science, but also women scientists.”

When Curie ventured to the US in 1921, people assumed that it would be a watershed for American women scientists, and that the French scientist would prove a feminine role model of competence that would pave the way for the advancement of women in science. The expectations were that Curie would somehow magically cure gender bias in science. While the double Nobel Prize winner did much for cancer with her research on radioactivity, expecting her to transform discriminatory attitudes was far reaching, if not a set-up.

The remarkable female scientist instead would unsuspectingly leave a legacy that historian Margaret Rossiter would name ‘The Marie Curie Complex”. Curie, of course, wasn’t able to change the sexist attitudes that existed against women in science at the time, nor was this on her radar. She was a scientist consumed with her work who never displayed interest in politics, gender or the advancement of women, and it was her undiluted obsession with science that enabled her breakthroughs.

Photo: Julie Des Jardins and the cover of her book

The Polish-born scientist, who was living in Paris, had won two Nobel Prizes, pioneered research on radioactivity (coining the term “radioactive”), and discovered radium and polonium by the time she arrived in America for the first time, in her early fifties. “Curie came to America right at the beginning when Nobel Prizes started to be awarded and science was becoming professional. She’s right on the cusp of the moment when science is starting to take its modern form,” says Des Jardins.

There were great expectations ahead of Curie’s US trip, which came about quite curiously. The publicity-shy Curie granted a rare interview to trailblazing female journalist Marie Meloney (who went by the pen name William B. Meloney) at her Paris laboratory. During the interview Meloney discovered that the Henri Becquerel, a scientist who (together with her husband, Pierre) discovered radium and pioneered techniques for purifying the element, could no longer afford to buy the substance. This because Curie had never patented her method and the processing of radium for cancer treatment and military purposes had driven the price of the element to $100,000 a gram.

Meloney declared that she would fundraise to get Curie the radium she needed to continue her research. After returning home, the writer-cum-socialite spent the next year petitioning women across the US for the money she needed to fulfil her promise to Curie. The French scientist’s maiden voyage to the US saw her travelling to the White House where she would collect the element, but the modest Curie was hardly prepared for the overwhelming fanfare that greeted her the minute she set foot in the US.

Des Jardins says that on her arrival in the US, Curie attended receptions at the Waldorf Astoria and Carnegie Hall. She appeared at the American Museum of Natural History, where an exhibit commemorated her discovery of radium. University choirs sang her praises and Ivy League institutions tripped over themselves to grant her honorary degrees. Every scientific club and chemistry society that could secure an audience with Curie held events in her honour.

“The marquee event of her six-week US tour was held in the East Room of the White House,” Des Jardins writes in Madame Curie’s Passion, her article for The Smithsonian. “President Warren Harding spoke at length, praising her “great attainments in the realms of science and intellect” and saying she represented the best in womanhood. “We lay at your feet the testimony of that love which all the generations of men have been wont to bestow upon the noble woman, the unselfish wife, the devoted mother.” It was a rather odd thing to say to the most decorated scientist of that era,” remarks Des Jardins, who explains that Curie has never been easy to understand.

“She was a pioneer, an outlier, unique for the newness and immensity of her achievements. But it was also because of her sex. Curie worked during a great age of innovation, but proper women of her time were thought to be too sentimental to perform objective science. She would forever be considered a bit strange, not just a great scientist but a great woman scientist. You would not expect the president of the United States to praise one of Curie’s male contemporaries by calling attention to his manhood and his devotion as a father. Professional science until fairly recently was a man’s world, and in Curie’s time it was rare for a woman even to participate in academic physics, never mind triumph over it,” writes Des Jardins.

“Men in the same field as Curie like (Robert) Oppenheimer and (Albert) Einstein are talked about in very different terms. Their atomic science has the ability to end wars but Curie is not even talked about in these same terms. She is seen as this maternal martyr and is written about in the same way that one would talk about Florence Nightingale, a woman who ministered to the poor and the sick,” says Des Jardins, speaking on the phone to iMaverick.

And so it was that during her tour of the US, that the media would typecast Curie as this perfect, maternal, altruistic figure. “This was by no means an accurate depiction of her. Curie was often neglectful of her daughters (one of whom, Irene Joliot-Curie, was her self awarded the Nobel Prize, jointly with her husband, for chemistry in 1935 for their discovery of artificial radioactivity – Ed) but the way she got depicted in the US media has created this ‘Madam Curie Complex’, this notion in the minds of women scientists in America and across the world that they could never manage to measure up to the perfection of Curie, so they wouldn’t try. Sadly, instead of her encouraging more women into science and getting more traction in the upper echelons of science, in many ways Marie Curie’s image has turned women off science.”

Yes there are Nobel Prize winning scientists like Rosalyn Yalow who won in 1977 for the development of radioimmunoassays of peptide hormones. “But the problem is that Yalow saw herself in Curie’s mould, which meant working 100-hour weeks in the lab, but also making sure she was home to give her kids lunch, dinner and do homework. She thought that being successful in science meant she had to be all things to all people,” says Des Jardins. “In many ways this is really debilitating. If you are a women who cannot live up to this Superwoman model – and unfortunately this is Curie’s unwitting legacy or rather how her legacy has been spun by other people, not Curie herself,” she adds.

Des Jardins believes that the myth that was spun about Madame Curie has haunted generations of women by empowering and liberating them, but also stigmatising and constraining women. “The historian Margaret Rossiter noted an inferiority complex in women after Curie’s tours of the United States in the 1920s, and for generations the Curie complex has continued to allow men to disqualify women – and women to disqualify themselves – from science,” writes Des Jardins in the introduction her book The Madame Curie Complex, which examines why technology and science remain predominantly male professions, and moves beyond the obvious to investigate the historical aspects of gender bias in science.

The numbers of women entering the field of science are now much higher than they have ever been, even in more staunchly masculine fields like theoretical maths and physics or engineering, but the numbers are by no means equal. But Des Jardins says one of the primary reasons for her writing The Madam Curie Complex is that the “women in science problem” is not a numbers problem. “You can hopefully change the culture of science as you add more women into it, but what we found, and what Summers revealed, is that adding more women doesn’t necessarily change the culture of science, if you refuse to see gender bias as a cultural problem.” She suggests that a way of changing attitudes in science could be by re-gendering the notion of what science is.

“This is particularly important in the more ‘masculine’ theoretical sciences where it is thought that your best work happens in your twenties and thirties. This cult of youth is pervasive and happens to be right around women’s prime childbearing years. Why not recalibrate this notion of where greatness lies to realise that you actually can be doing some of your best work after your forties or in your fifties and sixties?” asks Des Jardins, who believes science needs a new calibration after being defined as hyper-masculine as little as 50 years ago or less.

“There was this classic book written in the sixties called The Making of a Scientist in which a psychologist did research on Nobel scientists, who of course were all male. It was decided that what made the best scientist was someone who was anti-social, played with gadgets growing up, oftentimes was orphaned or completely detached from family relationships, not particular good daters in adolescence and a person who generally kept to themselves. The writer decided that these ‘typically masculine traits’ made a good scientist.”

Des Jardins makes a telling point. Recent research shows that the more obvious cries of discrimination against women in science could be something of a red herring. Cornell University researchers Stephen Ceci and Wendy Williams investigated 20 years of discrimination data on the status of women in the sciences to reveal surprising results.

The data shows that women aren’t being discriminated against when it comes to hiring, grant reviews or the publication of scientific papers, but are largely making personal choices about career preferences based on issues of fertility, family and happiness, or rather choose vocations where they “help people”.

In their book The Mathematics of Sex: How Biology and Society Conspire to Limit Talented Women and Girls, Ceci and Williams make telling observations about the research used by America’s National Science Foundation to direct its $135-million gender bias program. Ceci and Williams destroy research assumed by the foundation to be settled science, and write that the gender programme is based on data that has never been made public, and that a study used to prove discrimination has all but vanished into thin air. Then there’s the foundation sponsored study that shows “that, at many critical transition points in their academic careers (e.g. hiring for tenure-track and tenured positions and promotions), women appear to have fared as well as or better than men.”

This begs the question, when it comes to shaping the future of women in science, shouldn’t the most advanced scientific nation on the planet be using scientific methods?

In a column in Forbes, US equity feminist Christina Hoff Sommers points out the hypocrisy in the way the American scientific community is dealing with gender bias, a point the local scientific community would do well to heed as South Africa seeks to address the “women in science problem”.

“There are brilliant women working in all areas of American science, and there is a need for reasonable and sound initiatives to help them succeed,” writes Sommers. “But these efforts must be respectful, not contemptuous of the culture of American science. They should take into account the true state of the research on gender and science – not just the assertions of impassioned activists.”

“Advance marches on. Now any engineering, physics, math or computer-technology program that moves too slowly toward gender parity is inviting a government investigation and loss of funding. The nation’s leading programs are under pressure to adopt gender quotas and to rein in their competitive, hard-driven, meritocratic culture – a culture that has made American science the mightiest in the world,” she writes.

Given than gender discrimination has wreaked irreparable harm, the very least we could do to address this harm is to ensure that the disciplines applied to investigate and address gender issues in science are as rigorous as the most exacting used in the scientific method. And when science addresses gender issues, it will need to ask hard questions, including whether the programmes used to redress imbalances will harm scientific advancement itself. DM

Read more:

- Madame Curie’s Passion by Julie Des Jardins in Smithsonian Magazine;

- Sexual discrimination against women in science may be institutional in The Guardian;

- Science gender gap probed in Scientific American;

- Daring to Discuss Women in Science in The New York Times;

- Sex Discrimination in Science Continues, But Reasons Unclear in Wired;

- Watch Julie Des Jardins talk about “The Madame Curie Complex” on YouTube.

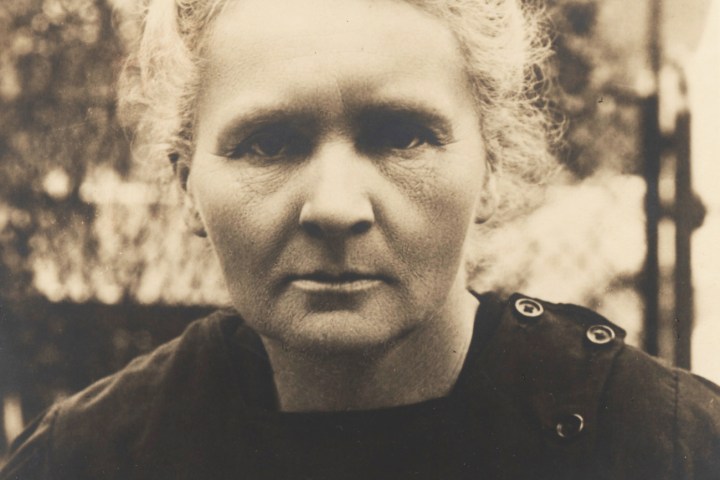

Main photo: Maria Curie.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider