Media

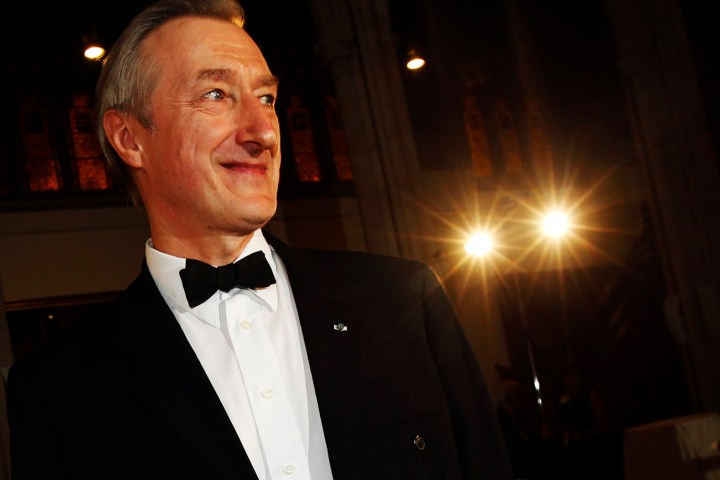

Fourth time a fitting ending: Julian Barnes wins the Booker

Julian Barnes, thrice a bridesmaid at the Man Booker awards, famously derided the award as “posh bingo”. Where Borges once claimed there was a cottage industry keeping him from the Nobel Prize, so it seemed for Barnes and the Booker. That’s all in the past now. By RICHARD POPLAK.

“I don’t believe in God,” Julian Barnes once wrote, “but I miss him.” This playful approach to metaphysics—the vaunted light touch—isn’t shared by his contemporaries, who have become more shrill by the year. Christopher Hitchens wants to kick Yahweh’s ass; Martin Amis has advocated death chambers for the aged; Salmon Rushdie has become a parody of the author of Midnight’s Children; Ian McKewen followed up Saturday with Solar, which is the equivalent of replacing a Chevy Nova with an ’84 Lada.

Barnes has been a member of this exalted company at least since the publication of Flaubert’s Parrot in 1984—his first de facto entry into the upper reaches of the British literary establishment. And while Barnes must be mentioned alongside the postmodernists and the pot-stirrers, he has always been more subtle, if not more genteel, than his peers.

His debut novel, Metroland, can be understood as something of a companion piece to the early work of Martin Amis—a meditation on being a young, English, suburban radical lay-about. The book details the passage of a man named Christopher, who is defined by his punkish opposition to bourgeois culture. Off he goes to Paris, where he misses les événements of 1968, mostly because he is too busy shagging. In the third section of the book, we catch up with him back in suburban London, now married and a father, where he must ask himself whether he has become what he once loathed.

Before She Met Me was a sequel of sorts; another grubby, sexually charged novel detailing the exploits of a compromised male character. But it was Flaubert’s Parrot that catapulted him into the canon—a book that was firmly of its time, but also meaningfully linked to the past: a postmodern novel about the pull of modernism. At once a study of an aging doctor named Braithwaite, an amateur Flaubert scholar who tries to determine which of the two stuffed parrots in French museums was actually Flaubert’s, it is also a book length musing on subjectivism—one of postmodernism’s primary concerns. The book was brilliant, literary and an antidote to the more bracing work of contemporaries like Martin Amis, whose Money was published the same year. Kingsley Amis famously flung aside his son’s book when a character named Martin Amis enters the narrative; Barnes’ postmodernist tack was always more considered, less vitriolic. (No word on what Kingsley thought of the book, but one imagines he would have dismissed it as too swottish.)

Yet, when it came time for the Booker judges to award the prize, Flaubert’s Parrot lost out to Anita Brookner’s Hotel Du Lac, a comfortable bourgeois novel that Christopher from Metroland would have burned in a pyre. (Money, by the way, didn’t make the shortlist.) This is one of the Booker’s greatest breaches of taste, and one of its more singular embarrassments, but not the last Barnes would be embroiled in. He was next up for the award in 1998 for the sci-fi-ish England, England, perhaps his funniest and most satirical work. On the Isle of Wight, Sir Jack Pitman has developed an England theme park, with a half-scale Big Ben, a mini Stonehenge and Princess Di’s grave. The book is principally concerned with Martha Cochrane, hired by Sir Pitman to be his “official cynic”, and her fall from corporate grace. It delivers a British dystopia that ranks alongside anything Alan Moore conjured up, and it is a vivid consideration of personal and national identity. Naturally, it lost the Booker to Ian McEwan’s piffling Amsterdam, a novella that is as slight as it is unworthy.

Barnes continued to establish himself as a primary British literary voice, publishing essay collections and novels at the rate of about one a year. (He wrote some fine pieces for New Yorker’s Letter From London between 1995 to 1998.) He was back at the Booker table with Arthur and George, perhaps the weakest of the three books to make it to the big stage, in 2005. On a shortlist with Ali Smith, Zadie Smith, Kazuo Ishiguro and John Banville, there was never any serious expectation that he’d take the prize. He didn’t; it went to John Banville’s The Sea.

Three times a cropper at posh bingo, Barnes could console himself with the fact that Beryl Bainbridge was a five-time nominee, and a five-time loser. After her death last year, he became the official bridesmaid. But with The Sense of an Ending, bookmakers were under the impression that Barnes’s time had come. The jury made it quite clear that they were looking for “readability”, as subjective a category as ever there was, and a 180-page novella from one of Britain’s more celebrated writers seemed like a lock for the prize. Up against a slew of first timers, 2011 seemed like Barnes’s year.

And so it has been. Salmon Rushdie has tweeted his congratulations and the establishment has nodded its assent. Barnes may now begin his long march to the Nobel Prize, perhaps in the footsteps of Borges, who never quite got there but certainly deserved to. The Sense of an Ending isn’t Barnes’s best work, but it is a fine short novel about memory’s imperfections. Like God, Barnes may not believe in Booker juries. But he has reason to thank them today. DM

Photo: Reuters

Become an Insider

Become an Insider