From its use by aboriginal South Americans in ancient times to its inclusion in the original formula for Coca-Cola, the active ingredient in the cocaine alkaloid has given human beings the confidence to express themselves forcefully. Which also means that users don’t know when to shut up. Was Sigmund Freud’s “talking cure” a direct result of his coke habit? A new book suggests it might have been. By KEVIN BLOOM.

“Is that coke in your bra, or are you just happy to see me?” So asked the MC at the Babylon Club, voicing one of the more memorable quotes from Scarface, the 1983 epic crime drama directed by Brian De Palma and scripted by Oliver Stone. There were a few more memorable quotes from the movie, as countless angry young men from those times until these might’ve told you, except they’d have been quoting the lines of Antonio Raimundo “Tony” Montana, the film’s druglord protagonist played by Al Pacino. Lines like, “I always tell the truth, even when I lie…”; “I kill a communist for fun, but for a green card, I gonna carve him up real nice. …”; and, unforgettably, “Say hello to my little friend…” But it was the MC at the Babylon Club who, with his trite asides, truly captured the ethos of the film. If any line stands for the illicit transglobal industry that Scarface sought to portray, it’s this: “Another great night here at the Babylon, right? Okay. All right! Do another gram, you’ll all be babblin’ on.”

Of course, relative to its thousand-year history – the remains of coca leaves have been discovered alongside ancient Peruvian mummies – cocaine’s bad rap is a recent thing. When the Spanish conquistadores arrived in South America in the 16th century, they learned (through enthusiastic sampling) that the locals’ claims about the leaf’s energising properties were true, so they formalised the trade and taxed each crop at 10 percent. In the 19th century, after European scientists isolated its active ingredient, Western medicine adopted it as a wonder drug – an Italian doctor named Mantagazza promoted it as a cure for “furred morning tongue,” flatulence, and off-white teeth; another Italian, named Mariani, put six milligrams per ounce into a “health-restoring” drink called Vin Mariani, which got publicly endorsed by Jules Verne, Thomas Edison, and three successive popes. Famously, it was also included in John Styth Pemberton’s original recipe for Coca-Cola, a formula that lasted from 1886 until 1906 (when the Pure Food and Drug Act was passed in the US).

The question that concerns Dr Howard Markel, however, in his new book An Anatomy of Addiction, is a question that extends well beyond cocaine’s powdered march from legality to illegality – all the way, in fact, into the manner in which the drug may have shaped our understanding of the present. Because Markel is interested in the cocaine addictions of two very specific individuals: Sigmund Freud, the father of psychoanalysis, and William Halsted, founding professor at John Hopkins Hospital and a deviser of many surgical procedures still used today.

Regarding the former, as the New York Times reviewer Dwight Garner notes, Markel is careful not to draw too close a link between the younger Freud’s dependence (he quit cold turkey at 40) and the mature professor’s hypotheses. Nevertheless, Markel does cite contemporary scholarship on the issue, especially theories that offer “nuanced contemplations on the connection of Sigmund’s cocaine abuse to his signature ideas about accessing unconscious thoughts with talk therapy; the division of how our mind processes pleasure and reality; the interpretation of dreams; the nature of our thoughts and sexual development; the Oedipus complex; and the elaboration of the id, ego and superego.”

Entertainingly, careful as he wants to be, floating beneath this opaque passage is a blunt assertion: Freud, the man who introduced the term “talking cure” to the world, was a cokehead. Welcome to the Babylon Club, one gram and you’ll be babblin’ on. Get it?

Of the other symptoms of cocaine use, specifically its aphrodisiac qualities, Freud seemed to tick all the boxes. Notes Garner: “[He] liked the stuff so much that between roughly 1884 and 1896, when he was in his 20s and 30s and in his major cocaine period, he tended on many days to have a red, wet nose… His letters to his fiancée were sometimes ripe with sexual feeling, of the kind a line of powder can incite. ‘I will kiss you quite red and feed you till you are plump,’ Freud wrote. ‘And if you are forward you shall see who is the stronger, a gentle little girl who doesn’t eat enough or a big wild man who has cocaine in his body.’”

As for Halsted, while the effect of his cocaine use on later generations was relatively insignificant, the effect on his own health was acute. Reviewing the book for Salon, Laura Miller observes: “Halsted shot up; Freud snorted. Halsted was rich and well connected; Freud was close to broke and struggling to make a name for himself in a profession afflicted by expanding pockets of anti-Semitism. Freud by all accounts figured out how to give up the drug, while Halsted, Markel believes, would go on occasional binges throughout the rest of his distinguished life. At least twice, Halsted resorted to staying at a Rhode Island sanitarium to get clean. He also used morphine, probably daily. Behavior that many of his students and colleagues shrugged off as eccentricity – lateness, incommunicado periods, a refusal to look people in the eyes (and thereby reveal his dilated pupils) – were read by a handful of astute observers as signs that the drug use he’d supposedly abandoned before arriving at Hopkins was still going on.”

It’s Freud, though, who holds the most interest here. Would the “talking cure” have been invented if the old master never put his nose down? Tough to say, but one thing is certain – if cocaine were a substitute for psychotherapy, Tony Montana would’ve been the most well-adjusted character in film history. DM

Read more:

- “The Lure of Cocaine, Once Hailed as Cure-All,” in the New York Times;

- “An Anatomy of Addiction: Sigmund Freud, Cokehead,” in Salon;

- Excerpt: An Anatomy of Addiction.

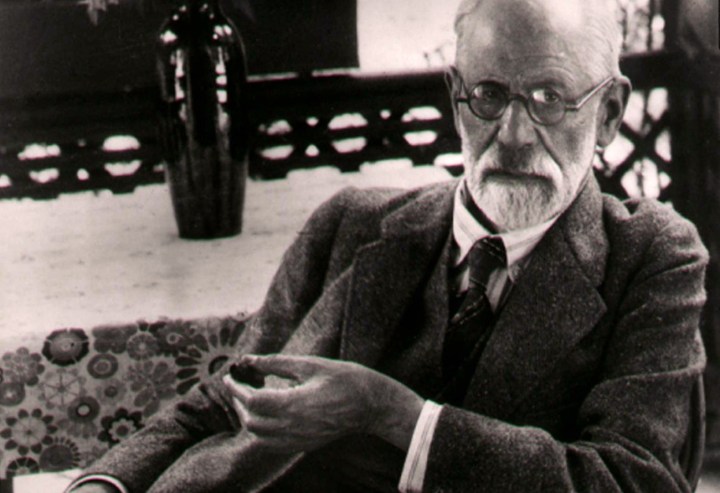

Photo: Sigmund Freud, circa 1929. (Reuters)

Become an Insider

Become an Insider