Business Maverick, Media, Politics

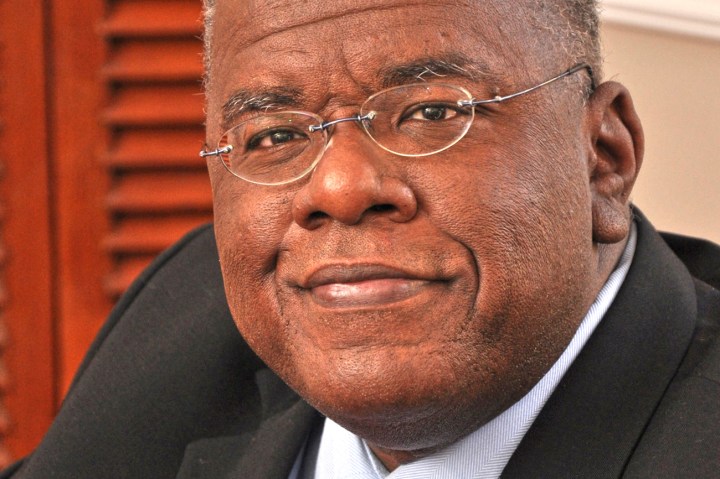

Jonathan Jansen: ‘Time to bring back the nuns’

It doesn't take a huge intellectual effort to understand that the long walk to a stable, strong South Africa will never be over. And while we're on that road, there will always be much to talk about. We can’t think of any better-qualified people to talk to than Jonathan Jansen. By EMILY GAMBADE.

Praised for being a talented and passionate educator, Jansen, head of the University of the Free State, brought integration to that erstwhile bastion of white domination along with handling the crisis in the wake of the Reitz Four. Blame it on his fascinating eminence, his humility, uncommonly strong common sense or his challenging views, it is no surprise that many would like to see him getting a shot at solving a gigantic problem called “SA’s educational system”.

Jansen is also known for his controversial columns in The Times, now compiled in his latest book, “We Need To Talk”. If there is one person the Daily Maverick would have an honest, almost brutally so, talk to about education and freedom and quality of expression in South Africa, it had to be the man not afraid to reply: “A poor schooling system is going to kill this country. (…) Instead of getting Cuban doctors, I would rather bring nuns back!”

Here’s the irresistible and sometimes rather inconvenient truth of Jonathan Jansen.

“I am at heart a teacher, an academic, I love my books, I love inspiring undergraduates to live better lives. There are people who are cut out for (politics), who have the chemistry for it, a thick skin. I would not enjoy it. I also think it is important for people like me – and there are many others – to occupy independent spheres. I am not attached to any political party. I have that space in which to applaud when things go right and to criticise when things go wrong.”

And when things go wrong, he has this rather rare talent of saying so loudly and clearly.

“For the moment, I don’t see education in South Africa going too far. If you think of education as 29,000 schools, 23 universities, and then technical colleges, (it is) not (going) very far at the moment because the politics of the public schooling is firmly retained by major trade unions, which do not care a damn about kids. They care about teachers, in a very narrow sense of their members. And if that means disrupting education for three months before an exam, so be it. That’s the kind of struggle that education has at the moment. I don’t have any political power so I can’t do anything about that, except to criticise, except to keep pointing it out, except to publicise it and its consequences. That has some effect, but obviously I’m not in control of the schooling system. I don’t think we’re going very far. And until we have a government and a political leadership that is prepared to wrest control of the public schooling (in the 75% of schools that are the most damaged), forget it, forget economic growth, forget public decency, forget democracy.

“Because corruption is not going to kill this country; crime is not going to kill this country; a poor schooling system is going to kill this country.”

So what would be the solution to improve our schooling system? Ironically, Jansen cites Zimbabwe as a model.

“It has placed a huge premium on education. It has a very strong educational culture. Remember, most schools there were not public schools; most of their schools, including the schools where Robert Mugabe went, were ran by nuns and priests. And the advantage of this is that they were strongly bedded cultures that reinforce the importance of education. We also had, at one stage, church schools in the majority. The Nationalist Party destroyed them in 1948 and 1953. They took them away thinking that they had to control the education of black kids. That was a major, major error.

“And then, of course, in the struggle against apartheid, even the schools that did work well, were destroyed. And we have never recovered. And that’s why the last thing South African kids today want to do is teach. They would rather be unemployed than teach. And if they choose teaching, it’s because they have no option and they are going into it resentfully rather than faithfully, passionately. And that’s the mess you have today. Instead of getting Cuban doctors into this country, I would rather bring nuns back! I’d fly them in from everywhere!

“Right now, we have a problem of absolutely no authority in schools, no culture of learning, absolutely no accountability to learning.;Now, what do you do? You don’t go say ‘no nuns’. You say ‘nuns’, looking at the kind of logical, cultural and social morals that support strong cultures; bring in people that can establish that. And right now I think that would be fantastic. We have just published this great teaching book and I was amazed at the number of kids, particularly black kids, writing how great teachers who had influenced them were mostly from church schools. They have positive memories from strong church schools when other schools were collapsing. It is not necessarily linked to religion. Most of those schools are no longer ‘religious’ ones. What they do is public service. The nuns come from Ireland or Scotland and they bring in a strong notion of respect for learning. I would certainly think that, given the level of crisis, to only leave it in the hands of the state is not going to take us anywhere. It is very pessimistic. I just don’t know how else we are going to get out of this.”

Education is at the epicentre of Jonathan Jansen’s thinking. It comes out in his regular columns, reminding us that the role of the media should not be limited to information, but give tools for reflection, prompting educated decisions.

“I think the media is part of the problem in our society. It has increasingly dumbed down the public conversation around trivial things like toilets. If you look at the front pages of our daily newspapers, there is this incredible fascination for nonsense like toilets. I am sure that if Julius Malema had said the Earth was flat, it would have been reported in the kind of sensationalism that such nonsense should not enjoy. So I am concerned that from an educational point of view, we are not really deepening discussions, debates, deliberations about the state of the nation, the economy, public schooling, social welfare and so on. I’m not suggesting that all the newspapers or media should become high-flying intellectual, snobbish spaces, but for heaven’s sake, give us more public media that actually force people to think! It is really scary that there is no publication at the moment, in this country, that gives me that. There isn’t really a broad public appeal newspaper that goes beyond, as I said, the sensational.

“Every country has trash in newspapers. I know the US very well and they have a lot of trashy newspapers, but at least there’s The Washington Post, The New York Times, the San Francisco Chronicle, newspapers that are worth reading and not just catering to our lowest impulses as human beings.

“Publications in South Africa are quite challenging. I think that’s why you had that media tribunal campaign in the first place. They are quite challenging of the state, of power, of politics. I don’t think there’s a lack of courage in taking people on, but it’s the way it’s done. Tell more about the culture of corruption, tell us more about the demise of public service, go beyond the ‘oh my God, the guy spent so much money on a car,’ and in some ways that might also attract the kind of censorship that people in power want to apply on the media, which is, the sensation. It does not educate the nation.

“I think I can say with a fair degree of certainty that, given the character of our democracy, there will always be tension between government wanting to climb down on the media and the media wanting to expose government, whatever the motivations. At the moment I don’t think government can win. Simply because of, as I said, the character of our democracy, the relative strength of our society, the sensitivity of the people in government. There are enough people who are broadly liberal in government, and I’m not saying liberal as a negative word, but who believe in freedoms of the media and a Constitution that can back you up on all those things. I don’t think this is Zimbabwe where civil rights were never strong, where the Constitution was never protective of fundamental freedoms. I don’t think we have singular thoughts at the top of the system as Zimbabwe has. So I don’t think one should overreact. At the same time, it doesn’t mean there aren’t very powerful people who would like to make sure they control the media by buying them out and you will see some moves around that in the next few weeks, because power doesn’t like exposure. Still, the balance of forces works against either side winning, and that’s good for democracy.”

Talking about democracy, Jansen adds: “My biggest concern is the very persistent disappointment that people have to live through in electoral cycles. Everybody descends on rural villages, promises them the world, and they still don’t have running water, safety, security from drugs, access to quality education. That cynicism that you develop in people about elections worries me. We struggled for a long time to be able to vote, but already we are beginning to hear people saying, ‘I’m not going to vote. Why should I vote? The last time I voted, nothing happened.’ The longer this democracy goes on, and the longer people don’t feel there is a tactical consequence to their voting, the more cynical they become about elections and about politics. And politics for me is a nice word; it’s a wonderful activity. I’m worried when I really don’t believe my vote makes any difference. I also don’t want to reduce democracy to elections. Democracy is fighting in the public space for the right to criticise; it is giving skills and quality education at schools and universities, so it mustn’t just be about elections. This is my greater fear: That the value of democracy, the meanings of participation, voting, get lost because people just don’t believe in it anymore.

“I am more optimistic about young people than I am about the current political system. It is not an individual thing. It is not that Zuma is good or bad. It’s about a whole leadership mindset that has to change and the only way is if we instigate the sense of political prices, because if the core of the crisis in public schooling is political, then it must be resolved politically. You can’t simply put in more money or training. You have to deal with the heart of the problem. You really need to open up conversations, be part of this rejuvenation of thinking, of optimism and so on. You need to give children a value system.” DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider