Media

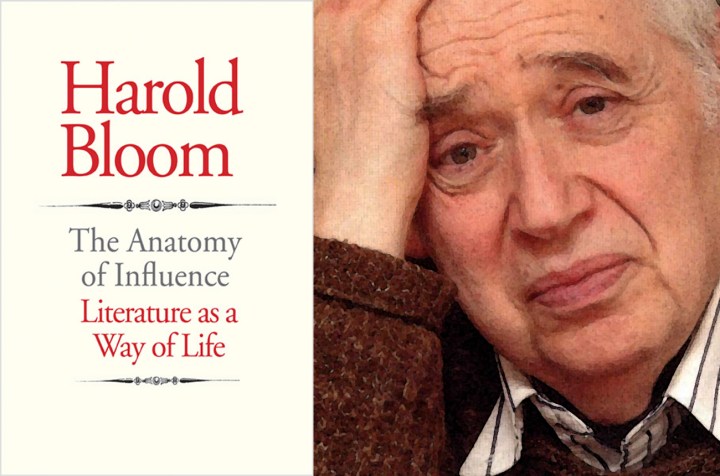

The enormously anxious influence of Harold Bloom

At the age of 80, after almost six decades taking on the Ivy League literary establishment, Harold Bloom has apparently retired as an author. Just released in the US, The Anatomy of Influence is supposed to be the last of his 40-odd books. Which begs the question: how will his own influence be judged? In giant measures, it seems. By KEVIN BLOOM.

In reviewing Harold Bloom’s The Western Canon, the late Frank Kermode – no slouch of a literary critic himself – remarked that his friend, the Sterling Professor of the Humanities at Yale, had “the chutzpah to put his stamp on the whole of literature from Genesis to Ashberry, rivaling the scope of hero-critics like Saintsbury or Curtius or Auerbach though more giddily adventurous than they were.” At the time, and perhaps more so today, very few people outside the halls of academia would’ve recognised the last four references, although everybody would’ve known what Kermode meant by “Genesis” – he meant that Bloom, in his sweeping commentary on the vast body of Western literature (published 1994), had started at the very beginning. Readers would also have been in no doubt as to what Kermode meant by “chutzpah”.

Born in New York in July 1930, Harold Bloom was fluent in Yiddish and Hebrew before he could string together a sentence in English. His parents were of the old school, Jewish émigrés who carted the values of Eastern Europe along with them to the South Bronx, but try as they might they couldn’t keep young Harold away from the new world’s poetry – at the age of ten, in the Bronx’s Fordham Library, the wayward upstart found and fell in love with the works of Hart Crane (while also, it should be mentioned, conducting a brief yet steamy affair with the Oxford English Dictionary).

By 1947 he had a scholarship from the State Department of Education to study at Cornell University, and by 1955 (at the age of 25) he had a PhD in literature from Yale. He would stay at the latter for the duration of his career, making a name for himself by challenging the orthodoxies of the establishment in the books Shelley’s Mythmaking (1959), The Visionary Company (1961), and The Ringers in the Tower (1971). The real breakthrough, though, was The Anxiety of Influence (1973), where Bloom systemised his most original theory: the notion that poets function best when they deliberately misread the works of their forebears. Also around this time, following a personal crisis, Bloom developed an interest in Freud, Kabbalah, and Gnosticism, idiosyncrasies that manifested themselves in texts such as Kabbalah and Criticism (1975), and The Book of J (1990; wherein the author magnificently argues that the Old Testament was written by a woman who lived around the time of David and Solomon, and that the patriarchal religion of Judaism was a ‘misreading’ by antecedent male curmudgeons).

But by far his most important work was The Western Canon, a major broadside against multiculturalist academics (that is, most academics) who read for a “social purpose”. In Bloom’s universe, reading is meant to be a solitary, aesthetic pleasure, and he places those who read for the betterment of society in the category of the “resentful” or the “absurd”. As he wrote in the aforementioned 560-page tome: “The idea that you benefit the insulted and injured by reading someone of their own origins rather than reading Shakespeare is one of the oddest illusions ever promoted by or in our schools.” In an interview granted a year after The Western Canon came out, he explained the thought thus: “We have to read Shakespeare, and we have to study Shakespeare. We have to study Dante. We have to read Chaucer. We have to read Cervantes. We have to read the Bible, at least the King James Bible. We have to read certain authors… They provide an intellectual, I dare say, a spiritual value which has nothing to do with organised religion or the history of institutional belief. They remind us in every sense of re-minding us. They not only tell us things that we have forgotten, but they tell us things we couldn’t possibly know without them, and they reform our minds. They make our minds stronger. They make us more vital.”

A stronger statement on the personal benefits of reading the classics you couldn’t find, and Bloom would later follow up on The Western Canon with a book that digested these sentiments for the masses, How to Read and Why (2000). Edging into his 70s by now, he wasn’t about to let up on the controversies either. In 2003 he stated that there were only four American novelists worth the price of admission – Thomas Pynchon, Don de Lillo, Philip Roth and Cormac McCarthy (a list notably free of female names) – and, when Doris Lessing took the Nobel Prize some years hence, he lamented the “pure political correctness” of the award to an author of “fourth-rate science fiction”. This was also the period that Naomi Wolf accused Bloom, her former professor at Yale, of having “sexually encroached” on her when she was an undergraduate by touching her thigh; it was a secret Wolf had apparently kept for 21 years, and one that Bloom steadfastly denied.

Now, at the age of 80, the man has just written and released what he claims is his swansong. The fact that Sam Tanenhaus, editor of the New York Times Book Review, has dedicated 4,000 words to the occasion is testament to not only Bloom’s ability to overcome adversity, but also to his enduring and enormous influence as a critic. In fact, the title of the book is The Anatomy of Influence: Literature as a Way of Life, which pretty much tells us all we need to know. Still, Tanenhaus seems to believe that in this so-called “last” of around 40 books, Bloom is expressing something akin to acceptance and quietude. “For [Bloom],” he writes, “great authors don’t merely imitate life or capture facets of being. They create ‘heterocosms,’ alternative but accessible worlds, open to us all. He had always been an esoteric populist, like his first subjects, Blake and Shelley. And he has achieved a new serenity, having made peace even with Yale, its campus now populated by ‘wonderfully varied’ students, wise in their own way. ‘Whatever one’s personal tradition,’ he has learned, ‘one teaches in the name of aesthetic and cognitive standards and values that are no longer exclusively Western.’ Anxiety, after all, is a universal condition.”

Which makes The Anatomy of Influence sound remarkably like an apology. It can’t be, of course, but it may count as a fitting end to the saga – after all, to read Harold Bloom finally making peace with his ghosts could be as compelling as reading everything that came before. DM

Read more:

- “Harold Bloom: An Uncommon Reader,” in the New York Times;

- Harold Bloom biography.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider