Media

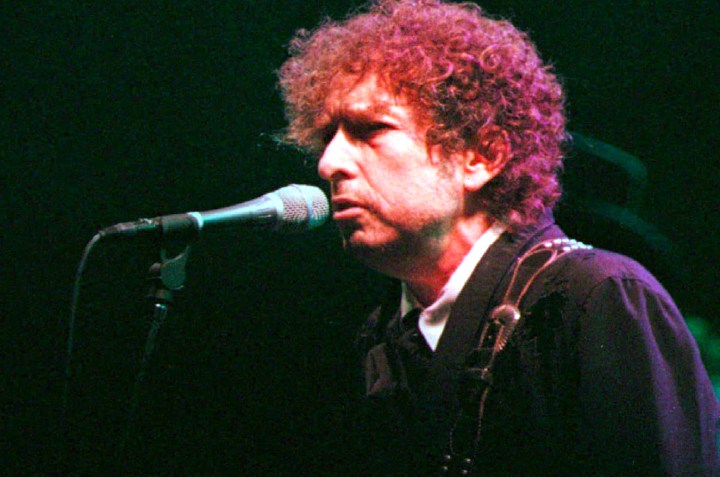

Dylan at 70: Still one step ahead of the persecutor within

From the moment he left his hometown of Hibbing, Minnesota, for the radical streets of New York in the early 1960s, Robert Allen Zimmerman has evaded every attempt that the world has made to pigeonhole him. This has been his enduring gift to us, and perhaps his ultimate message – the notion that we don’t need to be consistent, that our identities can and must constantly change if we are to fully live. On his 70th birthday, we therefore salute Bob Dylan, whoever he happens to be right now. By KEVIN BLOOM.

It was called, simply, Ray and Chloe’s place. It was in Greenwich Village, and was where Robert Zimmerman felt most comfortable before moving into a place of his own. The year was 1961 or early 1962; New York, according to the narrator of volume one of Chronicles – a narrator who, for reasons to be discussed below, cannot entirely be equated with the name on the book jacket – was trembling with an undercurrent of upheaval. One morning, when Ray and Chloe were out, Zimmerman awoke in this city of “radicals of all stripes,” in this top-floor walk-up near the Hudson River, and pulled open the drapes. He saw a bell tower, and contemplated the importance of bells in his life; he saw a priest in a purple cloak behind a man in a leather jacket, and thought about the millions of stories he could find if he just focused. Then he turned from the window and clicked on the radio, eventually dialing into a station playing Roy Orbison’s “Running Scared,” a song that reminded him of the futility of genre because for him it transcended genre, and was really all about “fat and blood”. Finally, Zimmerman wandered into the apartment’s library. And there the narrator of Chronicles properly lifted the blinds on his character.

“Standing in this room you could take it all for a joke,” he wrote. “There were all types of things in here, books on typography, epigraphy, philosophy, political ideologies. The stuff that could make you bug-eyed.” But amongst these reams of words were books that he liked, books that he kept coming back to. For instance, the war philosopher Clausewitz’s Vom Kriege, with which he had a morbid fascination – as a teenager, Zimmerman admitted, he wanted to go to West Point, and had even dreamt of commanding his own battalion. “When [Clausewitz] claims that politics has taken the place of morality and politics is brute force, he’s not playing,” Zimmerman observed. “Clausewitz in some ways is a prophet. Without realising it, some of the stuff in his book can shape your ideas. If you think you’re a dreamer, you can read this stuff and realise you’re not even capable of dreaming. Dreaming is dangerous. Reading Clausewitz makes you take your own thoughts a little less seriously.”

He also liked the French writer Balzac, he noted. “Balzac was pretty funny. His philosophy is plain and simple, says basically that pure materialism is a recipe for madness. The only true knowledge for Balzac seems to be in superstition. Everything is subject to analysis. Horde your energy. That’s the secret of life… He questions everything. His clothes catch fire on a candle. He wonders if fire is a good sign. Balzac is hilarious.”

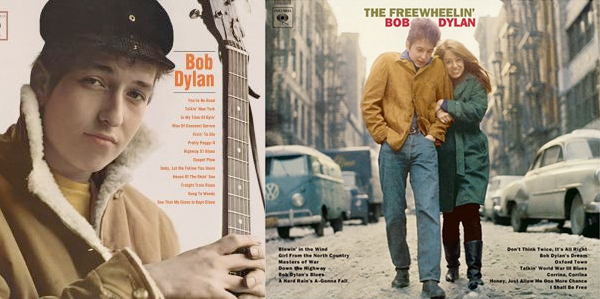

The question that such sentences bring up, though: do we believe the narrator of Chronicles? Zimmerman was then barely into his twenties; he still hadn’t legally changed his name to Bob Dylan, nor had he yet signed his management contract with Albert Grossman. He had gained some public recognition off a positive review in the New York Times, but mainly he was an unknown, another soulful and struggling folk artist in a city bursting at the seams with them. Even his first album, which was released in 1962 after he’d taken on the persona that would one day arguably become as large – in literary historical terms – as Shakespeare’s, was a flop (titled “Bob Dylan,” it sold only 5,000 copies). So was Dylan, in writing his autobiography in 2004 at the age of 63, reading some sort of poetic genius back onto his 20-year-old self that hadn’t existed in reality? Was he employing a narrative device in Chronicles that was cynically designed to feed the myth, a myth that he himself had nurtured and created through an immense ambition that never brooked setback or opposition?

The answer, at the same time, has got to be “yes,” no,” and “it doesn’t really matter.” Because what Dylan is probably best at – and he is undeniably brilliant at a lot of things – is returning to the world its primordial mystery. In an age of cynicism he is the uber-cynic, and so he often comes across as trusting and naïve; in an age of irrationalism he is the most irrational, and so his songs emanate a type of reason that encompasses both ambiguity and lived, observable experience. He believes in truth before the facts, in feeling before interpretation, although if you ask him (and legions of journalists have) he eschews any attempt to pigeonhole exactly what it is that he believes. He is willfully inscrutable, deliberately a paradox, and purposefully a man (*the* man) who embodies the notion of the impossibility of the coherent self.

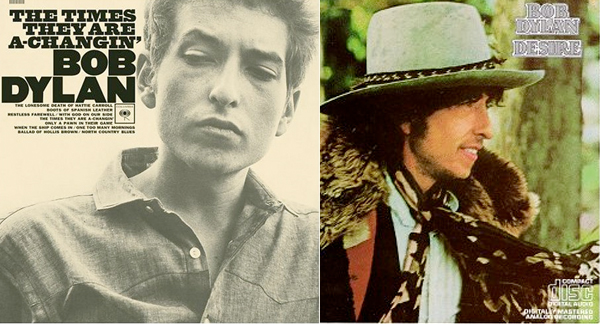

How else could a 20-year-old in love with the philosophies of Clausewitz become the 22-year-old songwriter of “Masters of War”? A song with lyrics such as: “Come you masters of war/ You that build the big guns/ You that build the death planes/ You that build all the bombs/ You that hide behind walls/ You that hide behind desks/ I just want you to know/ I can see through your masks.” If Dylan only highlighted the irony in this track as a sexagenarian – if he only came to Clausewitz later in life, figuring then that it would be cool to place Vom Kriege in the opening pages of his memoir – it doesn’t make much difference. As he knows better than anyone, the internal logic of a piece of art is way more important than the artist’s external consistency. And here, in terms of structure and form, Chronicles is as good as anything he’s ever written.

There’s therefore no better text, on the occasion of the maestro’s 70th birthday (May 24, 2011), with which to render his origins. “I was born in the spring of 1941. The Second World War was already raging in Europe, and America would soon be in it. The world was being blown apart and chaos was already driving its fist into the face of all new visitors. If you were born around this time or were living and alive, you could feel the old world go and the new one beginning. It was like putting the clock back to when BC became AD. Everybody born around my time was a part of both. Hitler, Churchill, Mussolini, Stalin, Roosevelt – towering figures that the world would never see the likes of again, men who relied on their own resolve, for better or worse, every one of them prepared to act alone, indifferent to approval – indifferent to wealth or love, all presiding over the destiny of mankind and reducing the world to rubble. Coming from a long line of Alexanders and Julius Caesars, Genghis Khans, Charlemagnes and Napoleons, they carved up the world like a really dainty dinner. Whether they parted their hair in the middle or wore a Viking helmet, they would not be denied and were impossible to reckon with – rude barbarians stampeding across the earth and hammering out their own ideas of geography.”

Obviously, in Chronicles, Dylan doesn’t give us much that’s purely biographical about his early years: we get practically nothing on his parents, on his school, on his life as a Jewish boy in Hibbing, Minnesota. Everything we do know about this person comes from other biographies, like Clinton Heylin’s Bob Dylan: Behind the Shades, where we learn that he was a quiet kid who kept to himself, and that when he got up on stage as a teenager to do wild and unhinged Elvis impersonations he had everybody in hysterics. It’s typical of Dylan to leave these mundane details to the professional biographers, and to concentrate himself on the never-ending task of self-mythologising. As a corollary to the broad mytho-historical sweep that he evinces in the passage above is the track “Jokerman,” from the 1983 album Infidels, with its unforgettable opening verse: “Standing on the water, casting your bread/ While the eyes of the idol with the iron head are glowing/ Distant ships sailing into the mist/ You were born with a snake in both of your fists while a hurricane was blowing/ Freedom just around the corner for you/ But with truth so far off, what good will it do.”

Who is Dylan singing about here? Himself, the man born, as per Chronicles, when the old world was ending and the new one beginning? Are those worlds represented by the snake in both of his fists? Is he maybe singing about the Messiah, as evidenced by the last lines in the third verse – “Friend to the martyr, a friend to the woman of shame/ You look into the fiery furnace, see the rich man without any name” – and the first lines in the fourth – “Well, the Book of Leviticus and Deuteronomy/ The law of the jungle and the sea are your only teachers”. Could he possibly be singing about himself as the Messiah?

Again, the answer must be “all of the above” and “none of the above”. Infidels was released in 1983, when Dylan was already well-established as a proto-mythical figure, and a few years after his conversion to Christianity and that unwelcome string of evangelical gospel records. But, as his 22ndstudio album (co-produced with Mark Knopfler), Infidels also signaled a move away from fundamentalist religion towards more personal themes of love and loss, with environmental and geopolitical issues thrown in for good measure. So while it’s oddly comforting to think of Dylan as a potential Messiah (a sublime poet and songwriter is a couple of notches up on a polygamist sex fiend, after all), it’s got to be noted that he always knew better than to announce his identity or intentions up-front. What’s more, there’s those enduring lessons he learnt from reading Balzac and Clausewitz to consider: horde your energy, and don’t take your own thoughts too seriously.

After Infidels, Dylan saw out the ‘80s with the critically-acclaimed Oh Mercy, an album that hinted at a slower, more contemplative period in songs such as “Most of the Time” and “What Was It You Wanted?” The same mood, and the more melancholic blues-based rhythm, came through on Time out of Mind, which won the Grammy for “Album of the Year” in 1998. Love and Theft, nominated for several Grammys in 2002, and Modern Times, named as Rolling Stone magazine’s album of 2006, extended the idea of this inward-focused and self-reflexive Dylan – a man thinking about getting old, missed opportunities, and a lifetime of heartache. Nowhere was this more evident than on the Time out of Mind track “Not Dark Yet,” which contains couplets like: “ Well, my sense of humanity has gone down the drain/ Behind every beautiful thing there’s been some kind of pain.”

But just as the world thought that it had Dylan licked – in the sense that it had finally got him where it gets everyone, that aging and impending death would remain his closing motifs – he shape-shifted once more. In October 2009, he released a Christmas album, Christmas in the Heart, applying his croaky voice to standards like “Little Drummer Boy” and “Here Comes Santa Claus”. Was Dylan being ironic? The New Yorker magazine thought so. “Dylan has a long and highly publicised history with Christianity,” the publication noted, “to claim there’s not a wink in the childish optimism of ‘Here Comes Santa Claus’ or ‘Winter Wonderland’ is to ignore a half-century of biting satire.”

More pertinently, perhaps, it’s to ignore the fact that Robert Allen Zimmerman was never a man who could be pinned down. It’s his ultimate gift to us, this notion that we never have to be, nor should we try to be, just one thing. And if there’s any couplet to quote back at him on his 70th birthday, any piece of rhyming verse that could conceivably be inscribed as an epitaph on his tombstone, it’s from the biblical track “Jokerman,” specifically the last two lines of the second verse: “Shedding off one more layer of skin/ Keeping one step ahead of the persecutor within.” DM

Read more:

- Chronicles, Volume One, by Bob Dylan.

Photo: Reuters.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider