Politics

Libyan crisis: Obama’s difficult moment

As US President Barack Obama prepares to address his nation on Libya, his task is increasingly complicated. In one speech he needs to convince them US actions are wise and in US interests, and the rest of the world that the US actions are wise and in global interests. To make things more interesting, his GOP enemies are sharpening their claws. By J BROOKS SPECTOR.

But let’s go back into history to understand the realities of today. The well-known story is that Harry Truman put a sign on his desk in the Oval Office that read, simply, “The Buck Stops Here”. The man had a way with phrases, him being also known for having nailed it by saying, “If you want a friend in Washington, get a dog”. The man knew a thing or two about the exercise of power. Anyway, the buck stopped on his desk because after all was said and done, as president he had the final say – but he understood he had to live with the consequences.

When the North Koreans crossed the demilitarised zone in 1950, Truman had the UN act on the untested doctrine of collective security and then moved as many US troops and equipment as were available from the occupation army in Japan to Korea to try to repel the North Korean armies. With just a bit of luck, the US – quickly renamed UN forces – just managed to hold the Pusan perimeter in the south-eastern part of the Korean Peninsula, thereby setting up the table for General Douglas Macarthur’s gambler’s roll on the Incheon landing that turned the war around.

This was a new kind of war – there was no congressional declaration of war as the constitution had outlined things – and there was no assumption of an all-out war until final, total victory. Instead, Truman had argued that he had the inherent power to use the armed forces as commander in chief, pursuant to a dutifully confirmed treaty – the UN Charter. This kind of argument had been built into the American constitutional arrangement from the beginning as a way of keeping the president – or congress – from sliding over the edge into oligarchy or dictatorship.

Until that moment, Congress declared war – the War of 1812 against Britain, the Spanish-American War, World War I and World War II – unless it was one of those very limited uses of the military as in various adventures in Central America and the Caribbean, or in quelling insurrections in The Philippines. But since the Second World War Congress hasn’t been called on to declare war, rather it has been asked to fund and support military actions carried out by every president since Roosevelt.

As a result, when these interventions went well – and quickly and cheaply – Congress tended to go along with a president, with the important exception of those Indochina wars that ran through the administrations of four presidents. By the time the Nixon administration was in its final death agonies, a Democratic Congress, thoroughly incensed by the duplicities of the executive branch, passed the War Powers Resolution in 1973 that was meant to enforce a position that military commitments can only run a limited time before the presidency had to come to Congress for a specific, formal vote of approval. Of course, presidents have argued that their constitutional role as military commander – there it is, right there in Article II of the constitution – can supersede such a mere congressional resolution, but, ultimately, they still had to come to Congress for the money to pay for such a commitment – that’s right there in Article I. As a result, presidents have, on the whole, found it wise and prudent to brief Congress, butter them up and earnestly solicit their support for their military adventures. As The New York Times defined it way back in the the tussles between the Reagan presidency and a thoroughly Democratic congress.

“Under the act, the President can only send combat troops into battle or into areas where ‘imminent’ hostilities are likely, for 60 days without either a declaration of war by Congress or a specific congressional mandate. The President can extend the time the troops are in the combat area for 30 extra days, without congressional approval, for a total of 90 days. The act, however, does not specify what Congress can do if the President refuses to comply with the act. Congress could presumably suspend all funds for such troops and override a Presidential veto.”

And so there is the sticky bit. To get to the point where Congress refuses to fund the military would be the equivalent of saying the two branches of government were in such fundamental, even irrevocable disagreement and conflict that there was little way forward, backward or sideways. Government meltdown.

Things are easier when it’s an invasion of some place like the tiny Caribbean island of Grenada which was run by a man who communed with flying saucers, only had a couple of dozen Cuban army engineers to fall back on as military reserves and who had made his neighbours in the Caribbean so annoyed with him that they voted to back the US invasion instead.

It’s a whole different thing when you’re using a significant chunk of the Sixth Fleet, hundreds of cruise and Tomahawk missiles, AWACs planes, flying drones and who knows what else. And when the goals of the air campaign are more than a little confused and the US defence chief, Robert Gates and all his underlings are having more than a bit of trouble saying how everything will end, and when, that makes it more difficult still. In short, the Obama administration has had more than just a bit of trouble enunciating what constitutes a win and when they’ll declare it. And when they will know it is over. Or as Gates responded on the weekend TV talk show, “This Week in Washington” when he was asked if the mission would be over by the end of the year, “I don’t think anybody knows the answer”. Not a confidence-building measure, that.

Photo: People celebrate atop a destroyed tank belonging to forces loyal to Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi after an air strike by coalition forces in Ajdabiyah March 26, 2011. Libyan rebels backed by allied air strikes retook the strategic town of Ajdabiyah on Saturday after an all-night battle that suggests the tide is turning against Gaddafi’s forces in the east. REUTERS/Suhaib Salem.

Part of this comes from the necessarily vague texture of UN Security Council Resolution 1973 authorising the no-fly zone – vague such that it could garner only votes in favour or abstentions and no veto from Security Council permanent members. The resolution doesn’t state that its goal is the end of the Gaddafi regime rather than simply the protection of innocent life; even though most of the participants in the air campaign’s coalition presumably assumed that was the goal. Now that it has become, effectively, a Nato-led operation with a Canadian general at its helm and the majority of the forces involved coming from France, the UK and the US, the ultimate goals issue has become more complicated still. Nato member Turkey is apparently still opposed to explicit regime change and Germany is opposed to the kind of incremental goal creep that comes with things like this.

In the case of Turkey, it is that country’s Islamic heritage that drags it away from attacking another Muslim society like Libya, regardless of its distain for the Gaddafi regime. And as for Germany, there is popular distaste for its military commitment in Afghanistan as part of the multinational force there (and the cost of the deployment); a public memory about Germany’s role in the Bosnian troubles and also, perhaps, some subliminal memory that the last time Germany fought a war in North Africa – well, it didn’t turn out terribly well.

And so, Barack Obama’s campaign in Libya may now be providing him with very little else besides aggravation. On the one hand, the confusion about the goals of this air campaign continues to bedevil the nations carrying out the air strikes and now enforcing the no-fly zone itself. Is the goal to end the Gaddafi regime? Or is it to prevent the Gaddafi regime from shelling its population in and around cities held by the rebels? Or is it to provide the kind of air support necessary for the rebels to effect at least a stalemate or hopefully to eventually capture the capital and end the Gaddafi clan’s hold on power? Any of this can end up producing growing numbers of civilian casualties – thus provoking stronger criticism about the campaign.

When Obama has been asked about his exit strategy, instead of a clearly articulated vision, he said things like:

“The exit strategy will be executed this week in the sense that we will be pulling back from our much more active efforts to shape the environment. We’ll still be in a support role, we’ll still be providing jamming, and intelligence and other assets that are unique to us, but this is an international effort that’s designed to accomplish the goals that were set out in the Security Council resolution.”

This obviously hasn’t set everybody’s mind at ease about explicit goals and objectives.

Within the Nato alliance itself there is that continuing split about these goals. The longer and deeper such disagreements carry on between Germany and, say, France, the more likely they may spill over to other issues. And that doesn’t even begin to take into consideration tensions within the UN or between air campaign supporters and the others.

But, of course, all this pales before Obama’s potential domestic political troubles over the Libyan campaign. This is now becoming intertwined with the upcoming 2012 presidential campaign and that will only get worse, rather than easier for him. The first Republican Party debates between potential candidates are only a few months away and some potential candidates are sensing a weak spot in the Obama administration over Libya. The moment the Obama administration needs more funding for this campaign (or Afghanistan or Iraq) there are going to be some dues to be paid in terms of further budget concessions to Republicans in other parts of the budget.

The White House, for its part, has stressed Obama’s catch-up briefings of Congress. The other day the White House’s press office explained:

“President Obama briefed a bipartisan, bicameral group of members of Congress on the situation in Libya. The President and his team provided an update on accomplishments to date, including the full transfer of enforcement of the no-fly zone to Nato, and yesterday’s unanimous agreement among Nato allies to direct planning for Nato to assume command and control of the civilian protection component in accordance with UNSCR 1973. Following the briefing, the President answered multiple questions from the members of Congress. The discussion lasted approximately one hour and took place in the White House Situation Room [with some lawmakers in person and some by phone].”

Whatever they’ve done, for some it has not been enough. While some Republicans have criticised Obama for waiting too long (if he had intervened earlier, they say, Gaddafi would now be history), others are criticising him for the vagueness of his goals in the Libyan campaign – is he or is he not aiming for the removal of Gaddafi? Surely, they argue, the US should be taking advantage of this upheaval to get rid of the would-be “king of Africa” once and for all.

However, still other criticisms come from within his own party. The left of his party seems deeply hurt that Obama of all people has launched a new military campaign instead of focusing like a proverbial laser beam on the pallid state of the economy. One or two really leftie Democrats have even muttered something about an impeachment under the War Powers Resolution. His critics are starting to note with more than wry smiles the fact that Obama is now a man with three wars on his plate.

Still others, Republicans and Democrats alike, are increasingly worried about how this nascent Obama doctrine will be applied to other rapacious regimes in the region. If Libya, they say, why not Syria or Bahrain – or even Saudi Arabia, if it should come to that? To date, the Obama administration has struggled to articulate the differences and how it has made such delineations.

Tied together with this is the conundrum of the Arab Spring for Obama. Early on he was criticised for clinging too long to Hosni Mubarak in Egypt, and then moving too precipitously in his criticism of leadership in other places. Obama administration figures seem publicly to be trying with less-than-total success – pretty much like everyone else – to predict where the next outbreak will come and what it will mean. And how they should respond.

For the Obama administration then, the air campaign and no-fly zone may eventually mean the final departure of Gaddafi from Libya, but with no clear objective in sight yet, there are all those down sides, not even counting the military ones. And even if Gaddafi goes, who or what kind of regime will rebuild the country after this war? All of these questions are surely plaguing the Obama administration even as it tries to disentangle itself from Iraq and Afghanistan and as it tries to engage with the rising forces of the Arab Spring version 2011. DM

For more read:

- Unrest in Syria and Jordan Poses New Test for US Policy in The New York Times,

- The Bites at Politico;

- If You Only Read One Sentence at Politico;

- Paul Harvey: The rest of the story in Politico;

- Why Obama’s Libya war coalition is the smallest in decades in Foreign Policy;

- More Republicans doubt Obama’s Libya action in Reuters;

- Obama’s Libyan mission creep? In the BBC;

- Libya: Museveni, Mugabe and Zuma condemn air strikes in BBC;

- Obama anxious to keep his toes out of Libyan water in the Guardian;

- The Problem With Partners in The New York Times;

- Two Senate Foreign Relations members criticize Obama on Libya in The Washington Post;

- Too Late and Too Weak in Slate;

- US appears to be closer to turning over command of Libya operation in The Washington Post;

- How War Powers Act works in The New York Times;

- RL32267 — The War Powers Resolution: After Thirty Years in the Congressional Research Service

- TITLE 50 CHAPTER 33;CHAPTER 33 – WAR POWERS RESOLUTION in the Cornell Law School;

- Obama rules out ‘land invasion’ in Libya in the AP;

- Gates Vitals in Time;

- Fight of the Valkyries in The New York Times.

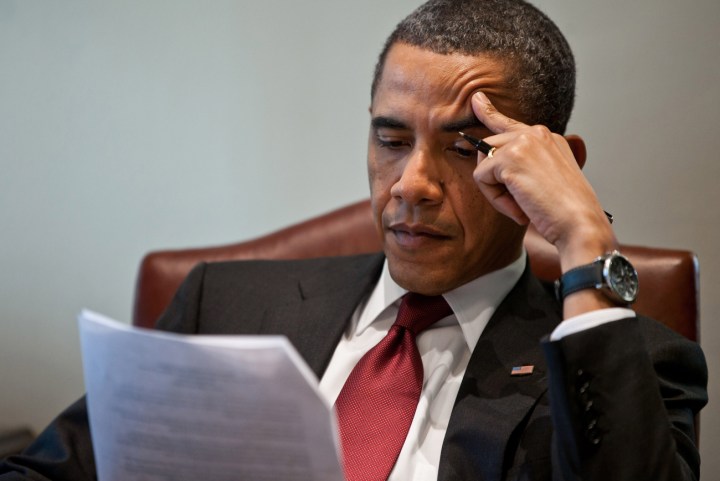

Photo: President Barack Obama reads a document in the Outer Oval Office as he prepares for a press conference with Prime Minister Stephen Harper of Canada, Feb. 4, 2011. (Official White House Photo by Pete Souza).

Become an Insider

Become an Insider