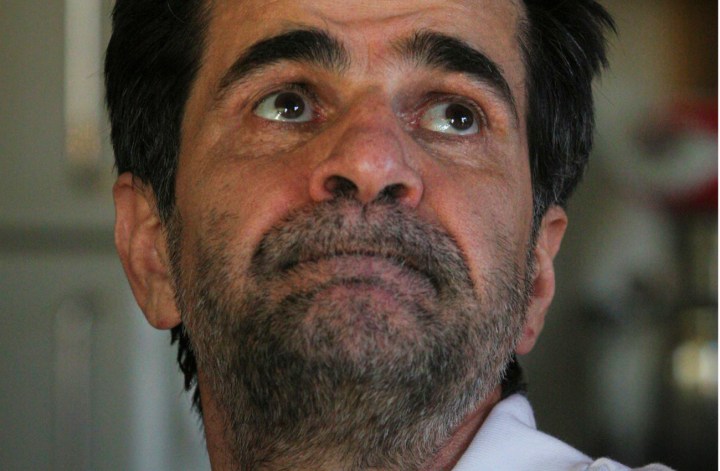

Following his arrest for publicly mourning protesters of Iran’s crooked 2008 presidential elections – street marches in which many were killed and thousands more thrown in jail – film director Jafar Panahi was, on 20 December, sentenced to six years in prison. The Iranian regime continues to pile injustice on injustice, and Panahi is just the latest victim. RICHARD POPLAK remembers his visit to a special cinema in a city of 14 million people, Tehran.

If south Tehran’s Café Entaracte has a signature feature, it must be the opaque window abutting the counter, canted slightly, looking out on a vista of dreams. Sometimes, what lies beyond the window is tenebrous – an enormous cavern, a slit of light like a gash across a massive white screen. On other occasions, the window reveals any number of scenes rendered in harsh primary colours – the hurly-burly world of popular Iranian trash cinema. Standing at the window, the viewer is a voyeur, a probing oneiricist. The sensation is, like so much Iranian art cinema, a self-reflexive, self-conscious endeavour; one experiences the uncomfortable, invasive act of watching.

Light reflected from the screen illuminates rows of empty seats – indeed the few remaining cinemas dotted across Iran are all but deserted. Nonetheless, the window reveals a fresh perspective on the power of cinema – a recusal to those who have judged film unworthy. The sensation is both claustrophobic and deliriously liberating – akin to a scene from Fellini’s “8 ½”: man stuck in traffic, trapped in a car, trying to kick through the windshield, sound muted except for his own breathing. This window, a screen on to a screen, is the most poignant monument to cinema I have ever encountered.

To find the window, the visitor must first negotiate the crowds on Jamhouri Ismaeli Street, walk from the lobby of the Cinema Jamhouri and up a staircase lined with poster art of American films set in light boxes: prestidigitation whodunit “The Illusionist”, horror sequel “Grudge 2”, straight-to-DVD actioneer “Edison”. (These have not been chosen for the films they represent, but rather because they represent film: for some reason, the ever-capricious ministry of culture has okayed them for public display). At the head of the stairwell, one encounters a scene that’s rare in Tehran, a city of 14 million souls with precious little public space. People smoke on couches, others sit on a bricolage of old furniture sipping hot drinks, Persian rugs thrown over a Formica floor, muted but distinct Western music (in this case, Sade, “Hang On To Your Love”), several potted plants, a bookshelf lined with periodicals, a long counter with jars of cookies and an espresso machine.

Watch a scene from Taste of Cherry:

Under the counter: Four backlit, striking images, culled from Iranian film and television. They are all the work of one man, filmmaking iconoclast Ali Hatami. The signature image is from the 1980s television show “Hazardastan” – a horse standing in the plush room of Tehran’s Qajar-era Gholestan Palace, under the brilliance of a chandelier. Hatami, a fierce original, said, “If we write in Farsi from right to left, that’s how we must make our cinema.” He developed a new visual idiom, a new way of representing the Iranian experience on film. But even he was not free from the ravages of the Islamic revolution that swept through the country in 1979. He died of cancer in the 1996, his films all but forgotten in his homeland.

Entaracte’s raison de’être is, to some extent, a way of maintaining Hatami’s legacy. His actor-daughter, Leila, star of the classic Iranian film “Leila”, and her husband, filmmaker and actor, Ali Mosaffa, have opened this café partly as a nod to Hatemi’s fading oeuvre, but also to extend the life of the cinema house below. “I had to beg my mother not to sell this place,” said Leila. “We had to sell our house and so many of our things. This was one of the only pieces we had left of my father – this cinema. And what’s more, all the cinemas in the city are closing. There are so few left. What is a city without a cinema?”

It’s a tragic question, and one the current Iranian regime is only too happy to answer. Iran was no picnic during the reign of the shah – we’ve said as much on this site, inviting opprobrium from vocal Iranian monarchist nostalgics – but the Islamic Revolution has been particularly unkind to Iranian artists. The regime has been obsessed with the notion of “Gharbzadegi”, or “Westruckness” – a concept first articulated in a famous book of the same name, written by Jalal Al Ahmed. The book and its ideas predate the rise of the clerics, but hardliners were only too happy to pilfer from it to buff up their revolutionary rhetoric. Al Ahmed believed Iranians were struck dumb by the razzle-dazzle of the West, and posited that the decline of everything authentically Iranian – like carpet weaving and lute playing and, if I read him correctly, Marxist-Leninism – was the cause and result of a series of Western “economic and existential victories over the East”.

Al Ahmed failed, however, to provide a convincing summation of what being an Iranian was, as opposed to what it wasn’t. By locating Iran on a map – plonked as it is in the middle of the world – the average person comes to understand how Persian culture can only be multifarious, a vast compound of East, West and everything in between. There are Iranians who are still resentful of the Arabic influence that came with the defeat of the Sassanids in the early Islamic era. There are those that look back to the French influence of the Qajar dynasty in the 18th century as the beginning of the end. But the truth is, by dint of geography and the rudeness of those who have stormed its borders on the way to somewhere else, Iran has always been a hodgepodge.

Watch the trailer for The Circle:

The Iranian spirit is uncrushable, and artists have, for the most part, been fearless in their desire to keep creating. Local filmmakers in particular have perfected an oblique way of encountering the world – self-reflexive, acknowledging the artifice of cinema, as if to say, “calm down, officer. This is but a movie.” There is no greater modern Iranian film than Abbas Kiarostami’s “Taste of Cherry” (insert rabid disagreement here), but the recently jailed Jafar Panahi was no slouch. His superb “The White Balloon” (written by Kiarostami), winner of the Camera D’or at Cannes in 1995, and “The Circle”, winner of the Golden Lion in 2000, represent a powerful body of work.

Panahi was arrested and sentenced for his art – “propaganda against the system” – and one needn’t be fluent in Farsi to understand what that “system” might be. Like his colleague Mohammed Rasoulof, also sentenced to six years hard time, Panahi was a threat to the regime because of his outspokenness, but also because his quiet, beautiful films acted as witness, reason, conscience. His work was a testament to art’s incredible ability to judge.

On my last visit to Enteracte, three years ago now, I sat at a table with Mosaffa, the filmmaker, and drank espresso. The afternoon light was especially rich, streaming into the café as a wide band of gold, picking up thick clouds of cigarette smoke. We talked cinema – precisely the purpose for which the café was built. Mosaffa told me his favourite Iranian film was called “The Cow” (1969) – a classic piece of Iranian neo-realist cinema. We spoke about David Lynch and Roman Polanski. The music was turned low, and the patrons – a photographer peering over a busy contact sheet, several students and some of Mosaffa’s cronies, talked quietly.

Mosaffa reminded me that this scene could present a problem to the authorities. “They could come in here and see this – wonder about the smoking, see that the veils are too high, and that there are women and men and Western music. And they could shut us down.” But this is a last ditch attempt for Leila Hatami and Ali Mosaffa to live in a world of cinema culture – one into which Leila was born – and one they are reluctant to see disappear. For now, the creative production is stalled, but their love for cinema is not.

I take one last look through the window into the theatre. There is a slapstick comedy playing on screen, a man with a pot on his head bumbling around. I watch for a few minutes and then turn to leave. The sensation is akin to waking. I hope for Hatami and Mosaffa that their own particular dream doesn’t die along with Iranian film, and the artists who are jailed defending their right to make it. After all, what is a city without a cinema? DM

Further reading: Deadline announcement of the arrests; Village Voice blog with some more details.

Photo: Iranian film director Jafar Panahi, following his release on bail, at his home in Tehran May 25, 2010. Panahi, who has been on hunger strike for more than a week, was released on bail of 2 billion rials (about $200,000), the official IRNA news agency reported. REUTERS/Stringer

Become an Insider

Become an Insider