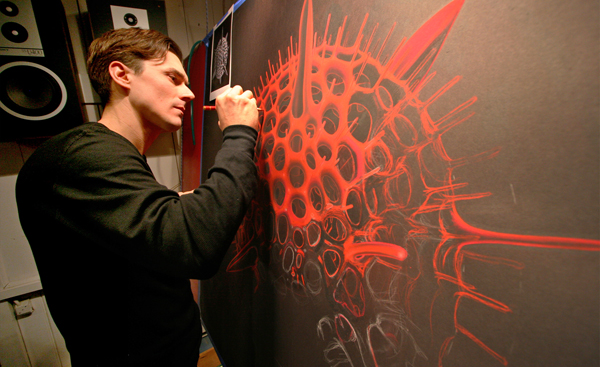

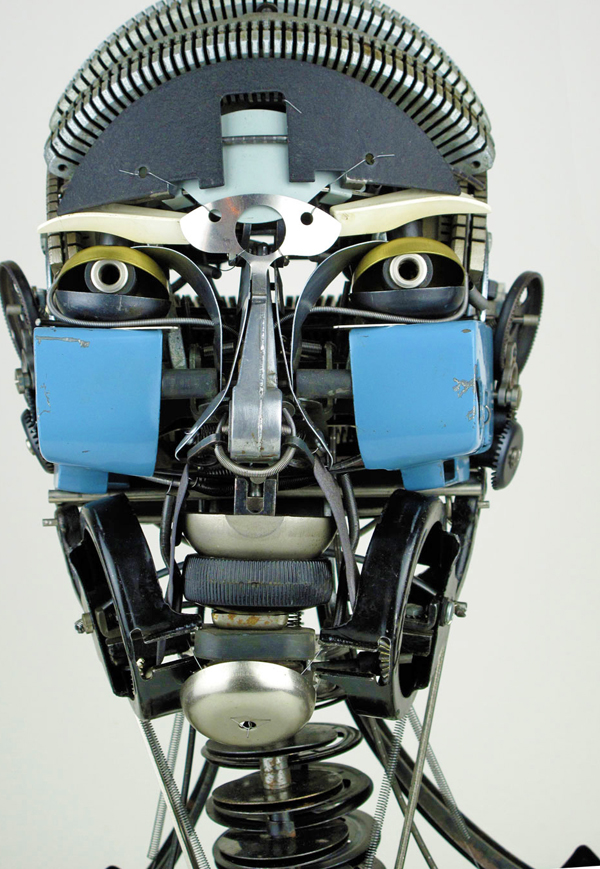

When we hold an iPad, start a car or switch on a blender, few of us think beyond the surface to the “heart” of the machine and its evolution in form and function. Jeremy Mayer is different. He’s an artist who looks deeply into the soul of a machine, loving nothing more than taking typewriters apart to recreate anatomically accurate forms that embody a distinct sense of being. By MANDY DE WAAL.

The product of the blue-collar working world of the Midwestern US state of Minnesota, Jeremy Mayer knew he was different fairly early on. “I grew up in a family of non-artists and was a withdrawn kid who drew a lot. My first memory of being interested in typewriters was when I was about nine or 10. My mother had an Underwood, which is a cast-iron, very heavy, old typewriter.” Mayer loved playing on the typewriter, but secretly wanted to take it apart and see inside the machine.

Mayer finally had the chance in his early twenties not intending to make anything of the parts, but as the pieces lay there he thought how similar they looked to those “build-it” toy kits. You know, the Meccano type, with nuts and bolts and metal beams normally given to boys to construct cranes, bridges and whatever a young brain can imagine.

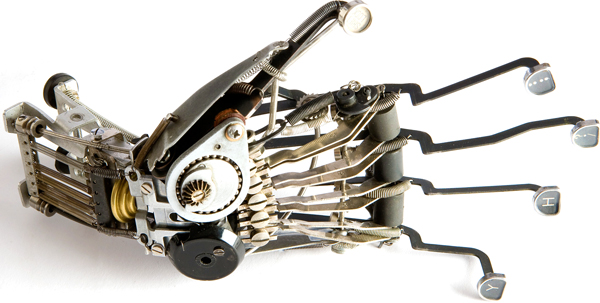

The first model Mayer made was a goofy looking dog which hardly impressed his artist wife and her bohemian friends. “I very soon started making figures that emulated real anatomy and I did a lot of bugs and small animals to begin with. In a few months I had done a full-scale human figure. The excitement was immediate and lasting. It’s now 16 years that I’ve been doing this.”

For Mayer, turning old typewriters into art is a love, a compulsion born of a need to repurpose the old into the new. “When I started building these sculptures, recycling was important to me. I was interested in doing sculpture, but couldn’t afford clay or stone or the kind of space to make the scale of sculpture I wanted to make. I couldn’t afford mould-making materials and all the tools required for sculpture. I felt fortunate that, with my assemblage, all I needed was a couple of screw drivers, a small set of tools, and room to store the typewriters. I didn’t need to buy anything – except the occasional typewriter.”

Nowadays Mayer gets most of the typewriters from his friends or people who know about and appreciate his art. Old typewriters turn up on his doorstep with notes. He gets Tweets or messages with photographs of broken machines from people who want to know if this is his kind of typewriter. “Many of the machines I take apart are defunct or beyond repair. I would say 80% of them are broken, but I also take apart some pretty nice ones.” At this, the soft-spoken and demure artist breaks into laughter.

Part of the beauty in Mayer’s work is that his sculptures aren’t soldered, glued or welded together. They are fitted together piece by piece in a painstaking and frustrating process. “I fit the pieces together like a puzzle. It is very difficult and time consuming. It requires a lot of frustrating play. Sometimes, I will assemble an entire piece and spend 40 or 50 hours on something, and then decide it’s not going to work and have to take the whole thing apart and start all over again.” The struggle has given Mayer patience. “There is a degree of struggle involved, but it has taught me it’s possible to match your vision no matter how much time it takes.

“As far as putting these pieces together, it is a very visual thought process where I have an inventory of thousands of parts taken from many, many typewriters, probably 60 or 70 at a time. It is all there in my head. I have a pretty good memory and remember all the parts I pull out of typewriters. I categorise them and put the parts in bins. When I am working at my bench, the parts almost jump up off the table and rotate in three-dimensional space where I can see the whole thing and discern whether I can use that part and where it fits.”

Doing what he does, Mayer is deeply conscious of the relation between people and machines. “I have started to see the way we put ourselves into our machinery and into our technology. We do this in a way most people don’t think about.” Mayer’s view is that machinery and technology have evolved from the inorganic and functional to the aesthetic because humanity has added more and more of itself to its machines in an effort to assimilate them. “There has to be a little piece of us in machines and technology for us to relate to them. The forms have to be familiar and the shapes have to be drawn from nature or from our own experience.”

View Jeremy Mayer’s work at an art show called Machinations:

Like most artists, Mayer has to deal with the vulgar reality of paying bills too. “I have to make a living and I do that very poorly,” he laughs. “If I was to fear being poor or afraid of making ends meet, I wouldn’t get any artwork done. Artists say all the time that you have to do 80% of what pays the bills and 20% of what you love, but it is a slippery slope and all too often you have to ask artists where’s their 20%? They wind up doing 100% of what makes them money. In my case, I am not interested in making a product to sell. I am interested in following through with this thing that is interesting to me and which I think is a sound artistic statement. I just have so much time invested in it that I have to keep it up. I do my best to make ends meet, but often I am on the edge, which is fine. It is very stressful sometimes and it is hard because I have a daughter. But you know…” Mayer’s voice trails off. He chokes up a little. And then he says: “You know it’s hard.”

The responses to Mayer’s work are mixed. “Some people say it is not art and that it is purely craft, which isn’t bad. I don’t mind that. Some people say it is amazing. Some people hate the idea that I am taking apart typewriters. Some people don’t care.” Again the gentle tone of Mayer’s voice is broken by playful laughter. “Some people are creeped out by it. Some people think it is gorgeous.”

Those who get Mayer’s work are people who appreciate the aesthetics of design, construction and anatomy. Doctors, architects, designers and other artists have enormous respect for his work because they understand his sculptures of the human body and other creatures can take hundreds of hours and up to 40 or 50 machines.

A man who’s never taken formal art classes, Mayer’s gift for taking the expired accretions of our existence and transforming them into beauty in a world where old, unloved metal litters landfills, makes him all the more remarkable. If only he could make it work for his other 80%. DM

Visit Jeremy Mayer’s website. Read more: Jeremy Mayer Turns Typewriters Into Art in Oakland Magazine, Typesculpting — a conversation with Jeremy Mayer in Convozine, ‘Sexy’ 6-Foot Sculpture Nude IV Is Made of Typewriter Parts in Wired.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider