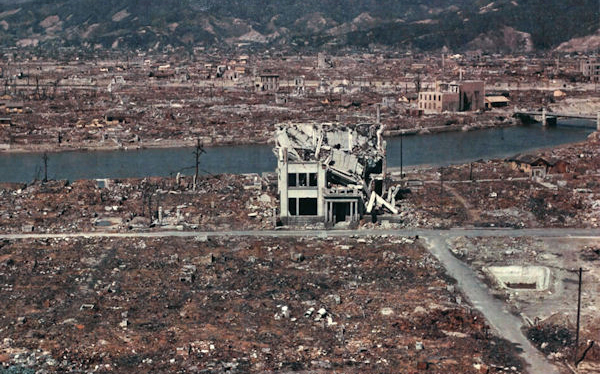

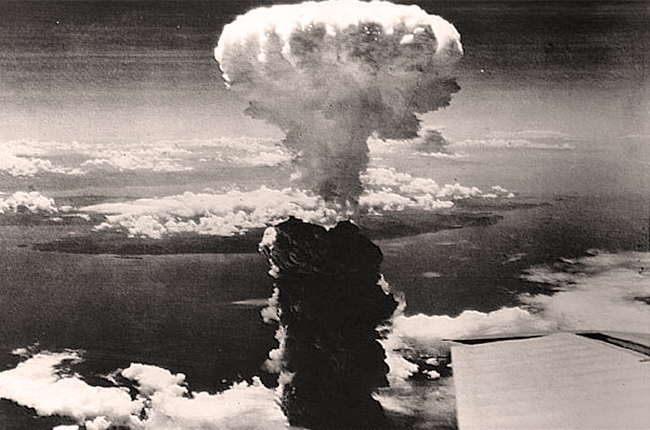

On 6 August 1945, just after 8:15 in the morning, a silvery B-29 bomber flew over the Japanese city of Hiroshima and dropped only one bomb. It killed tens of thousands, grievously wounded many more and virtually annihilated the core of that ancient city. The world instantly knew that, from that moment on, nothing would ever be the same.

This fearsome new weapon had only recently been perfected by a team of thousands working in secret on the Manhattan Project, led by the brilliant, deeply driven physicist, Robert Oppenheimer. When he saw the first successful test of an atomic device on 16 July 1945 in the New Mexico desert, Oppenheimer presciently quoted a Hindu sacred text: “Now I am become death, the destroyer of worlds”.

Three days later a second bomb devastated Nagasaki and the following week, Japan unconditionally surrendered to the Allies.

And yet, it was near happenstance that Hiroshima became the first target of a nuclear explosion in warfare. Six years earlier, a group of refugee scientists (mostly Jewish researchers led by Leo Szilard who had been forced to flee Europe ahead of the concentration camps) prevailed upon Albert Einstein to write to president Franklin Roosevelt. Einstein was the world’s superstar scientist and people like Leo Szilard felt only he could make an adequate impression on Roosevelt.

Photo: Albert Einstein and Robert Oppenheimer. (LIFE)

Einstein agreed to sign a note on 2 August 1939 that would call Roosevelt’s attention to developments in German science that indicated its physicists were making real strides in atomic research that could lead to a Nazi A-bomb – and its baleful consequences for the world. In the end, Einstein’s letter was sufficient to provoke the US to speed up nuclear research and, when the country entered World War II after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbour, became the impetus for the Manhattan Project.

The irony was that the German scientists had done their sums wrong – their bomb almost certainly would have been a dud, even if they had pursued it with typical Teutonic thoroughness. Moreover, Germany surrendered before the American bomb was ready for action. But, in the meantime, the bitter, savage fighting across the Pacific towards the Japanese home islands, island by island, fed a deep prejudice towards the Japanese that became an almost visceral hatred of anything Japanese.

In the weeks after Germany’s defeat, and the grim casualty statistics of the assault on Okinawa were fully digested, American commanders were brought up short as they thought about how they could justify the loss of yet another quarter of a million soldiers that would happen through the invasion of the Japanese main islands. In fact, the military had become dependent on statistical methodologies. They had become a key tool for evaluating air raid effects, determining military logistics and resupply patterns, and producing projections of troop requirements and losses. (There is, in fact, dispute about what the exact casualty projections of invading Japan would be – some said 50,000 others five times that.)

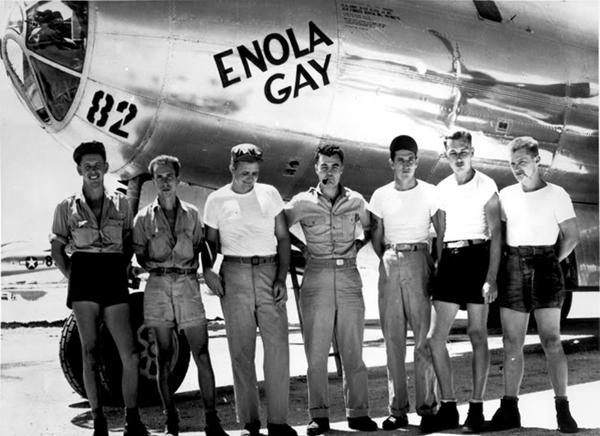

Photo: Enola Gay crew, with commander Colonel Paul W. Tibbets, Jr.in the middle.

But, whatever the number was, after four years of war, it seemed just too much to pay. The A-bomb seemed just the deus ex machina needed to end it all. Sort of a “one bomb, one surrender” solution. And, depending on which historian you read, perhaps a shot across the bow of the Russians to let them know who was in charge.

And this is where the tale diverges. For Americans, the A-bomb was the logical culmination of a pattern of a nationally mobilised industrial warfare that began during the Civil War bringing the fruits of research and science and enormous productive capacity to bear on otherwise intractable military problems. The bomb, when it was loaded into the “Enola Gay”,the name painted on the nose of the B-29 Superfortress bomber, became the sword to help Americans avenge Pearl Harbour, the ignominious Bataan surrender and the prisoners’ death march, and all those other early defeats in the Pacific – plus the sacrifices that followed, year on year.

But, for the Japanese, it became the moment that opened a door to the country’s first-ever military surrender to a foreign power. For many it seemed quite literally to have come out of the blue, without warning. Their storyline of World War II had something of a blank space after the country’s early victories. Hiroshima and then Nagasaki seemed something that just happened to them, transforming their national narrative from that of an all-conquering land into one that became a unique moral witness to the potential horrors of a future global atomic holocaust.

Watch: The original Hiroshima and Nagasaki video

Fifteen years ago, Washington’s Smithsonian Institution determined it would commemorate the dawn of the atomic age and the end of World War II in a special exhibition. The original plan was to enshrine the entire Enola Gay in the Air and Space Museum, hold a conference on these important issues and then publish a commemorative scholarly volume from the conference.

Things did not go as planned. First the Enola Gay’s wings were too big to fit into the exhibition hall so only the fuselage could be displayed. Then the exhibition organisers became embroiled in an increasingly nasty, public squabble with veterans’ organisations that accused the curators of being too solicitous of the Japanese and far too flippant about the sacrifices of America’s World War II veterans.

Photo: Hiroshima’s devastation was near-total.

As plans progressed, historians such as Barton Bernstein had been arguing that using the A-bomb on Hiroshima and Nagasaki had been unnecessary, and perhaps it was actually designed to be a warning to the Russians not to take advantage of the collapsing Japanese military. And perhaps even an act of warfare against non-military, civilian targets – although Hiroshima was, in truth, also a great military arsenal and munitions workshop. Authors such as Bernstein asked: Why didn’t the US military demonstrate its new bomb on an uninhabited island rather than on a city of 500,000 people, or simply wait for the Japanese to surrender as their military will inevitably collapsed? Not surprisingly, arguments like this didn’t sit very well with the American veterans and much of the public, either, many of whom saw them as a reprise of anti-Vietnam War and anti-military feelings by those who never fought there.

All of this quickly ended up in the media where the squabbles were hashed and rehashed, over and over. Eventually the Japanese came into this fight as well. Some historians used this argument to bring up Japan’s record of horrors in war, its inability to teach its difficult history in full to its post-war students or to admit to war-time atrocities – and its obdurate reluctance to make amends to the victims of its prisoner of war camps, its military brothels or its chemical warfare experiments. By this time the Japanese Embassy in Washington decided to issue a big book of selections directly from its leading, nationally used history texts in both Japanese and English to head off the firestorm. By the time the exhibition closed, you could just about hear Smithsonian officials breathing a sigh of relief and looking forward to putting together less contentious, more anodyne exhibitions on religious conflicts, climate change or genocide.

Photo: Girls pray after releasing a paper lantern on the Motoyasu river in remembrance of atomic bomb victims on the 65th anniversary of the bombing of Hiroshima August 6, 2010. Japan marked the 65th anniversary of the U.S. atomic bombing of Hiroshima on Friday with the United States represented at the ceremony for the first time. Seen in the background is the gutted A-bomb dome. REUTERS/

Without doubt, however, Hiroshima has become the pre-eminent symbol of runaway technology that can put an end to life on Earth. As such, it leads directly to the terror embedded in a bitter, and incredibly funny, satire like “Dr. Strangelove,” just as much as it animated the Ban the Bomb movement of the 1960s, or today’s push for progress to limit the world’s nuclear arsenals and to end the spread of nuclear weapons to regimes like those in North Korea or Iran. And each year on the anniversary of the atomic attack, the river that runs through the city is crowded with small, rice-paper lanterns each with a candle inside, remembering a soul who departed on that date.

And so, inevitably perhaps, we circle back to Albert Einstein, the reluctant father of nuclear energy. Some time after World War II a journalist asked him what weapons would be used in World War III. Einstein, it is said, paused for a minute and then responded, “I know not with what weapons World War III will be fought, but World War IV will be fought with sticks and stones.”

By J Brooks Spector

For more on the decision to make and then use the bomb, as well as the controversy over its use, read the website of the National Air and Space Museum, the Air Force Association, Lehigh University, H-Net, Foreign Affairs, George Washington University’s National Security Archive, the Atomic Archive and About Inventors.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider