Arts and culture minister Lulu Xingwana's recent outburst over the Constitutional Court exhibition of “dangerous” photographs by Zanele Muholi served one important purpose: It put the spotlight on the South African government’s tragic treatment of arts and culture. Read on and weep.

It is a truism to say South Africa’s arts and culture sector is in turmoil. Now, there’s good turmoil and there’s bad turmoil. A culture and a country roiling from the shock of the new – such as were impressionist Paris in the 1880s, the remarkable German cultural efflorescence between 1920 and 1933 or New York City of the abstract impressionists in the post-World War II years – are turmoil in the good sense of the word. Assertive, vigorous new ideas and influences making both culture and society magnets for the creative from around the world.

On the contrary there is turmoil or crisis in which a society has government officials muddying the waters about what is officially deemed acceptable art (or not) and then holding back funding (or offering it) to disburse rewards on political grounds. Crisis can also describe a situation where funding becomes harder and harder to obtain, forcing creative organisations into the financial wilderness.

No points for guessing which kind of turmoil we in South Africa now find ourselves.

Consider the following. In a story that came out this past week (although the events actually took place last year), minister of arts and culture Lulu Xingwana stormed out of the opening of Innovative Women, an exhibition of photographs by Zanele Muholi, under curator/artist Bongi Bhengu, at the Constitutional Court, ostensibly on the grounds that the mildly explicit photos of women embracing each other could have harmed the tender sensibilities of children (oblivious of what they see on television every day). This is notwithstanding the fact that the court already has an international reputation for the quality of its own art collection, as well as for nurturing works that speak to the intersection of art and rights.

Photo: Zanele Muholli. (Sally Shorkend)

Depending on which day Xingwana’s comments were reported, (and they did metamorphose over the week), she was either worried about the effect of the pictures on small children, or she was upset that she couldn’t figure out what the pictures were about or she found the work was anti-feminist and anti-revolutionary – whatever that may mean. Even if we were to take her faux-solicitude about the tender feelings of children on board, remember this is the same ministry that had paid R300,000 to support the exhibition in the first place.

This is some pretty strange management. Even a really poorly run bureaucracy will brief its minister on what it has supported and why, before sending that same minister out to open the thing for which it has just paid. If for no other reason than self-preservation. The argument that she didn’t know what she was getting herself into doesn’t wash – unless the department has absolutely no idea what it’s doing. (Okay, that sounds entirely true. – Ed)

The subsequent argument, advanced by one of its spin doctors, that the minister was protecting women’s rights and reaffirming her stance as a revolutionary by boycotting the work, makes no sense either. How does publicly boycotting, then castigating female artists for portraying women (even if the work is not to everyone’s taste) somehow make the attacker a defender of women’s rights or a promoter of a 21st century revolutionary agenda?

This is pretty embarrassing and appalling all by itself. But let’s link it to a few other developments. This same department, in the name of fiscal austerity, has just cut the National Arts Council’s grants budget to a starvation level of around R14 million – what, 30 cents a person in the country? Not so long ago, the NAC’s budget was three times that amount.

This is the NAC we’re talking about, an organisation that evolved from the democratisation of South Africa post-1994. Established out of a broad, intensive consultative process with other cultural figures that was part of the larger democratic evolution of the 1990s, the NAC was intended to provide support for the arts beyond political considerations and to take up some of the space left by the closure of the previous four provincial performing arts councils – the organisations that were the cultural support wing of the apartheid social order.

But the NAC was also supposed to have sufficient independence and funds to provide essential support for new, innovative, exciting – even dangerous – art, as well as support more established, but clearly not profitable, or not-for-profit, arts and cultural organisations.

Today’s NAC crisis, in part, is similar to the crisis in arts sponsorship in the US in the 1980s, as one congressman after another lined up to castigate the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) and to threaten its very existence after it aided exhibitions that included some of Robert Mapplethorpe’s astonishing, but clearly homoerotic, black-and-white photographs or works like Andres Serrano’s controversial Piss Christ. The former seemed to some to be a government celebration of homosexuality and the latter a bald irreligious or anti-religious statement with government money.

As punishment for crossing some sort of aesthetic threshold, the NEA’s allocation was eventually cut back and, to avoid future controversies about its funding policies, it agreed not to fund individual artists. In return, Congress effectively agreed not to pick apart its individual projects, budget line by budget line, every single year.

Back in South Africa, the NAC’s own recent comments, criticising the ministry that funds it, shows just how dire things have become: It now only has R14 million in grant funds for the entire year for every art form in the entire country. Or as the council itself said: “These cuts, coming shortly as they do after the department of arts and culture’s termination of the task team established to advise on cultural programme for the World Cup celebrations, are a sad indictment of a lack of serious resource commitment to arts and culture.”

It goes on to say the department is even more culpable for another current funding morass. It has unceremoniously pulled the plug on its own prior commitment to provide up to R150 million for special arts and cultural funding during the World Cup. About a year ago, the department encouraged arts and cultural groups to approach them with ideas that would shine a spotlight on the country’s own arts and culture and to take advantage of a world spotlight on South Africa in 2010. While no one seems to know for certain, there are dark rumours that the fund has evaporated as money was siphoned away to support a huge contingent of people to China a while back and a somewhat smaller group to France more recently. Or one can simply put it up to the usual waste, fraud and mismanagement allegations. With so many senior officials at the department under suspension, it’s really hard to tell. And, of course, no-one is coming forward to clarify things.

Now, with less than 100 days to go to the 2010 Soccer World Cup, the department has not announced any plans for showcasing the country’s art and culture during the sports extravaganza. It has given no funding commitments. It has made no public arrangements and has not apparently contracted any performers to do anything. In fact, at a recent meeting for cultural managers, speakers for Johannesburg and Gauteng essentially told the gathering of arts organisers: “We’ll help you publicise what you’re already planning to do by way of flyers, brochures and pamphlets, but don’t look to the government for any money to do anything. Sorry.”

The fear now is that at the very last minute the government will suddenly discover it has found some money and will again turn to its usual suspects to pull together some sort of cultural show – you know, the usual dancers, beads and drums and stuff – but the new, the innovative and the daring will be locked out yet again. And, of course, given her public statements, if Xingwana has anything to say about it, the country’s arts on display would almost undoubtedly consist of big heroic revolutionary statues, heroic revolutionary music from a generation earlier and, the minister’s true love, rural craftwork.

Consider, for example, Xingwana’s unhappiness at a work commissioned for the World Summit on Arts and Culture in Johannesburg in September 2009 and paid for by the department in a special allocation for the summit. This extraordinary theatre piece, a collaboration by installation artist Brett Bailey and choreographer Gregory Maqoma with its protest against xenophobia, gained critical public acclaim, but criticism in private from the minister for its lack of heroic, indigenous content – especially its use of music by a noted Congolese composer.

Don’t get the wrong idea, this author really loves baskets and traditional dance and sees them as expressions of South Africa’s creativity beyond formal art conventions. But if the country plans to leave an impression on several hundred thousand visitors from around the world, we should have been planning for years to put on a show that is something more than an array of handicrafts, no matter how dazzling.

Putting the best face on the NAC’s problems, its new CEO, Annabell Lebethe, wrote that the council will try “to form strategic partnerships with the private sector and international donors in realising the joint industry vision for the South African creative community”. Or, in less-bureaucratic language, “we really hope someone else will turn up to fund things because we can’t”.

The third leg of government support for the arts in this country, the Lottery Distribution Trust, actually has considerable money it could disburse, but its own bureaucratic complexities mean it has generally been giving out less than a third of its available funds and its processes often seem arcane or impenetrable to outsiders. In fact, arts organisations are often observed going round and round from the NAC to the department to the lottery in an increasingly desperate effort to find enough funding simply to stay afloat.

This 2010 mess is simply a microcosm of the larger picture. There is little or no long-term commitment to artistic excellence in South Africa. Add to that the terrible confusion in the minds of senior leaders as to what “art” is supposed to mean for a nation, and you have the key elements of our current artistic predicament.

Increasingly, the country’s most innovative and challenging artists are moving or working elsewhere where their talents may be better appreciated and supported. The man who may be the country’s leading contemporary artist, William Kentridge, goes abroad to New York to stage his work. Good for him, yes, but unless you get to the Metropolitan Opera really soon you may never see Kentridge’s critically acclaimed production of Dmitri Shostakovich’s opera The Nose.

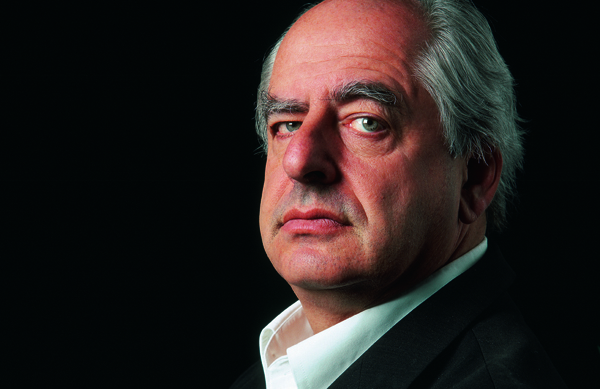

Photo: William Kentridge. (Sally Shorkend)

Similarly, you have to race to catch the occasional local performance by dancer-choreographers such as Robyn Orlin (now living in Germany) or Vincent Mantsoe (now living in France). Others such as composer Kevin Volans or filmmaker Neill Blomkamp are expatriates for other, more personal reasons, but the country doesn’t make much of an effort to lure them back for extended periods – or to teach others – except when their own choices bring them here.

Although a recent survey by Business Arts South Africa (Basa) showed that overall, corporate sponsorship had grown over the past decade, big, sustained sponsorships for the edgy and challenging seem to be fading. FNB, for example, announced it will no longer support the Dance Umbrella, the country’s most important annual dance showcase, after two decades of being associated with it. True, a few new sponsors such as expatriate South African property developer Eric Abrahams have stepped up to fund entirely new institutions like the Athol Fugard Theatre in Cape Town and its resident company, Isango-Portobello, but, on the whole, the country’s business leadership is shirking from the kind of social investment in long-term cultural growth and development that the government’s three agents, the National Arts Council, the lottery and the department of arts and culture are meant to support.

At a recent seminar in Cape Town, the formidable president of the Kennedy Center in Washington, DC, Michael Kaiser, the man who has rescued cultural groups from a plunge into the fiscal abyss in Europe, the UK and the US, said a new approach was crucial for arts groups. Kaiser said organisations needed to build funding and partnerships that reached beyond current problems, were flexible enough to take advantage of future windows of opportunity, and above all, that could build an organisational ethos that planned half a decade ahead to take advantage of unexpected, but potentially useful opportunities. As Kaiser said in response to his persistent questioners, maybe it is already too late to take care of the connection between the arts and 2010, but this just means it is imperative to take 2011, 2012 and 2013 in hand now.

Kaiser’s insights make the South African situation even more tragic. With the ruling party in turmoil and the country with a government that is neither efficient nor effective, these are indeed dark times for South African arts and culture. And, sadly, there is not even a glimmer of hope on the horizon.

By J Brooks Spector

Read more: TimesLive, Mail & Guardian, Mahala

Photo: Arts and Culture Minister, Lulu Xingwana, info.gov.za

Become an Insider

Become an Insider