Business Maverick, Politics

Analysis: After Nersa’s ruling, which way for SA’s industrial policy?

Once upon a time, South Africa had an industrial policy which provided businesses with a way to compete internationally; it was called “cheap electricity”. That ended today.

The old industrial policy was simple and effective, but what replaces it is complex and uncertain. The old industrial policy allowed South Africa and Mozambique, for example, to become big aluminium suppliers to the world, even though they have no alumina.

The old industrial policy was based on lowering key input costs for business, and it applied generally to all businesses, albeit to a greater or lesser degree depending on the municipality in which the business was situated.

The idea was to use the lower cost of capital that flows from Eskom being a state enterprise, to build electricity power plants cheaply and produce electricity cheaply, lowering a key cost for all businesses.

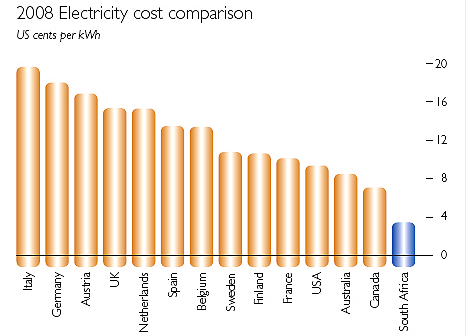

We will soon see how effective it was, because now it’s gone. According to Eskom’s 2008 annual report, electricity in South Africa in 2008 cost half of that in Canada and a fifth of that in Germany or Italy. With a 27% increase last year, and a 25% increase this year, with two more in the pipeline, SA will be on a par with the US and Australia. In other words the advantage is gone.

The new industrial policy announced by trade and industry minister Rob Davies last week seeks to go exactly in the opposite direction, selecting winning sectors with a bias towards encouraging totally new business, and not necessarily helping existing business. The primary aim is to increase employment.

Whereas the old system involved little direct interaction between government and business, the new system means getting plans approved by government before benefits will accrue. It means ticking boxes specifying all of government’s pet peeves and predilections: for example, the business concerned will have to employ lots of people, preferably young people.

It’s not a terrible idea to help start new businesses or to help young people get a job. But will it work?

Meanwhile, as regards Eskom, government is heading in a totally new direction, seeking to use competition to drive prices down, with the introduction of independent power producers (IPPs).

It is also seeking to “renegotiate” – in other words get more money – from the long-term contracts it does have. According to Fin24.com, public enterprises minister Barbara Hogan says Eskom and BHP Billiton are discussing a review of Billiton’s electricity agreements.

These are critical. The aluminium smelters at Hillside and Bayside, and also Mozal in Maputo, function because the price paid for electricity fluctuates according to the aluminium price. This is no trivial issue: the smelters use almost twice as much electricity as the city of Port Elizabeth.

It also means that when the aluminium price goes down, as it did during 2008 and 2009, Eskom’s finances go to pot. Eskom’s profit plunged in 2008 to R974 million compared to R6.4 billion in 2007, even though it actually produced more electricity. (The R6.4 billion profit was boosted by huge gains in Eskom’s derivatives book of R4.3 billion, but still, the profit from the business itself still halved).

These smelter contracts are a big headache for Eskom now, but they were set in relation to the aluminium price to reduce the risk of building these enormous smelting plants. Without that agreement, the plants would probably never have been built.

Even if Eskom does not manage to convince BHP Billiton to pay more, by seeking to renegotiate these contracts, the parastatal is sending a message that it’s no longer in the business of facilitating the creation of large industrial enterprises – at least not until it has sorted out its own financial problems and built huge new coal power stations.

Will this massive change in approach actually work? It may, but you have to say the omens are not good.

Consulting engineer Andrew Kenny argues in Business Day against the free-market model for electricity supply that government appears to be following. The key is something called “beta”, the technical term for a company’s volatility which determines the cost of borrowing. The cost is lowest for government because the risk is lowest. Private companies have additional risk. A beta of one means that your company has the same risk as the private sector average.

“In October last year, in its price increase application to Nersa in the multiyear price determination for 2010-11 to 2012-13, Eskom said its beta was 1.1. Eskom believes that it is more risky than the average private company. This is mad.” writes Kenny.

“This explains the high requested price increase. Eskom’s average selling price is now 33c/kWh and it is asking for 35% increases for the next three years. This would bring the price to 81c/kWh in current money or 68c/kWh in 2010 money (assuming 6% inflation).

“Eskom obviously hopes to fund its new stations to a large extent on electricity sales, pay off the stations quickly and then make huge profits out of them. What it should be doing is to fund them mainly on debt and then manage the debt in a responsible manner.”

In other words, Eskom is aiming not to create a base for industrial growth, but to be itself a function of industrial growth.

This could have all kinds of strange effects. One will be that, suddenly, IPPs could enter the market. Kenny says economist Brian Kantor has drawn up a simple spreadsheet showing how a new station can fund itself on a price of 50c/kWh, much less than the price Eskom is asking for in three years’ time.

Already some big companies are thinking about it. Anglo American CEO Cynthia Carroll has said Anglo is considering ways of producing its own power for its mines, either with government or on its own.

Is it possible that SA could go from having an undersupply of electricity to having an oversupply? Too often decisions are made only with the most recent disaster on mind.

Eskom’s desire to flip on to a new track comes as government tries to change tracks too. Government is flipping from a generalised form of support for industrial development to specific industrial support initiatives.

Yet while people worry about their electricity bills, general appreciation for the momentousness of this dual change does not appear to have registered anywhere near the levels it should have. Think earthquake of about 8.2 on the Richter scale.

By Tim Cohen

Read more: Business Day

Photo: An aluminium smelter can use almost twice as much electricity as the city of Port Elizabeth.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider