Multimedia, Sci-Tech

Dear Pluto: eighty years on, we still love you

On 18 February 1930, 23-year-old junior researcher at the Lowell Observatory in Arizona, Clyde Tombaugh, discovered Pluto. Hailed as Planet X that humanity was for some reason desperate to find, it was the stuff of dreams and pure romance. Today it drifts forgotten and unexceptional. How things change.

The work was, how shall we put it, boring. Clyde Tombaugh was a mostly self-educated young researcher who was making up for his lack of academic achievements by being what every good astronomer in those days needed to be: a patient, methodical fella. By February 1930, he’d already clocked-up a whole year of working with blink comparator, a truly clever machine: two photos of the same portion of the sky, but taken at intervals of several days, were inserted into it and the victim, er, scientist, would flip from one to another. As stars are, for all intents and purposes, immovable objects, the whole variety of asteroids, comets, and other objects in the solar system would be seen jumping from one photo to another. On 18 February 1930, the object that jumped looked like it was Planet X, a legendary ninth planet behind Neptune that the observatory’s benefactor, Percival Lowell, had spent his life searching for until he died in 1916.

In those days, the US was in the throes of the Great Depression and the rest of the world didn’t feel much better. Planet Earth desperately needed something to celebrate and finding the long-sought brother was an opportunity as good as any. The news of the new planet’s discovery spread around the world at the speed of light. (Well, radio waves actually.) In what was one of the earliest examples of global crowd-sourcing, Tombaugh and his bosses at Lowell Observatory received more than 1,000 name suggestions, with Pluto, Minerva and Cronus making it to the final three. In the end, Pluto, suggested by Venetia Burney, an 11-year-old schoolgirl from Oxford, won by acclamation, and the new planet was announced to the world on 24 March 1930.

Pluto was a great name to give to a planet. Okay, it was originally named after the Roman god of underworld (Hades in Greek mythology), but soon after a new addition was made to Mickey Mouse’s family, the lovable dog was named in honour of the newest planet. Pluto was destined to be loved by everyone. Not even the small fact that the new radioactive element was named Plutonium and that it turned out to be an integral and terribly frightening part of nuclear weaponry could distract Pluto fans.

And yet, not much was known about Pluto. From the beginning, it was obvious there was something strange about it. While every other planet was orbiting the Sun on more or less the same plane, Pluto’s orbit was a strange, elongated ellipse with a full 17 degrees tilt to it. For a good 20 years at the time, Pluto was not even the furthest planet from the Sun, as its orbit would regularly bring it inside Neptune’s. It was obviously a very small body that differed markedly from its ice-giant neighbours, Uranus and Neptune. We really didn’t know much more than that. And, yet, we didn’t let the facts stop us from celebrating our nine-planet solar system. Until we found out that Pluto has a moon of his own.

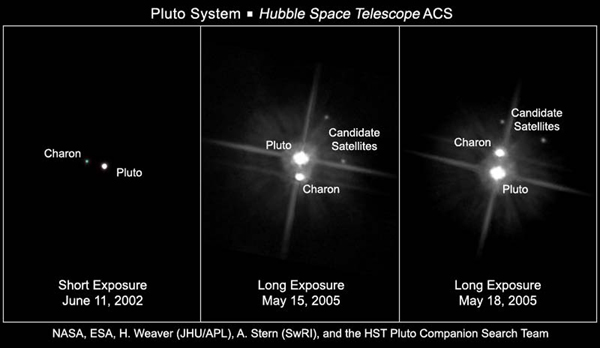

In 1978, astronomer James Christy from US Naval Observatory Flagstaff Station found that a highly magnified image of Pluto had a dimple. It turned out to be a proper moon, and it was fittingly named Charon, after the ferryman who ferried the dead over the river Styx to the underworld.

Photo: Pluto’s satellites, Charon, Nix and Hydra (NASA)

But that’s where the problems for Pluto the planet started: after Charon’s discovery, astronomers were, for the first time, able to properly measure its mass, and it turned out to be miniscule, only 0.2% of Earth’s mass and a long way down from the original assessment of Pluto being roughly the size of our planet. Then it turned out that Charon is relatively large, and that both Pluto and its satellite actually orbit around a centre of gravity residing somewhere in between then.

Many scientific eyebrows were raised after Charon’s discovery, but Pluto still toddled its way around the Sun as a fully fledged planet for a while, until the Kuiper belt was discovered in 1992. This trans-Neptunian region is, according to estimates, home to more than 70,000 Kuiper Belt Objects (KBOs) larger than 100km in diameter, a thousand of which have been discovered since. Suddenly, Pluto’s planetary “exceptionalism” evaporated faster than the comet’s atmosphere approaching the Sun.

It was immediately obvious that Pluto was no more than just a large KBO that happens to be nearest to the Earth. In 2004 Haumea was found and in 2005 Makemake – both comparable in size. It was scientifically impossible to defend Pluto as a planet anymore. Yes, it does have a smidgeon of atmosphere, 1/700,000 of Earth’s, to be precise, and it has two more miniscule satellites, Nix and Hydra. But a planet it ain’t.

Photo: The New Horizons mission is scheduled to visit Charon and Pluto in July 2015.

The final decision was made by the 26th International Astronomical Union in 2006. The gathering in Prague mercilessly downgraded Pluto to scientifically-correct status of dwarf-planet, where it joined Haumea and Makemake, the largest object in the Asteroid belt, Ceres, and the largest object in the so-called scattered disc (even further from the Sun than the Kuiper belt), Eris, which was discovered in 2006 and turned out to be bigger than Pluto. This grim deed was done despite the worldwide campaign to keep Pluto as a planet. (A new word was added to the English lexicon: the verb to be “plutoed” means to suddenly fall from stardom to the ranks of the ordinary, to be demoted.)

And yet, many an astronomer, including your own reporter, spent countless cold nights under crystal-clear skies over the last 80 years, knowing that the solar system ends with the God of the Underworld being the last sentinel before the unimaginable abyss of the Space beyond. Scientific truth about the chaos at the edge of our system, or not, the image of Pluto guarding us was so much more comforting.

So, dear Pluto, no matter what they say, you’ll always be planet to us.

By Branko Brkic

Read more about Pluto discovery, history and structure here.

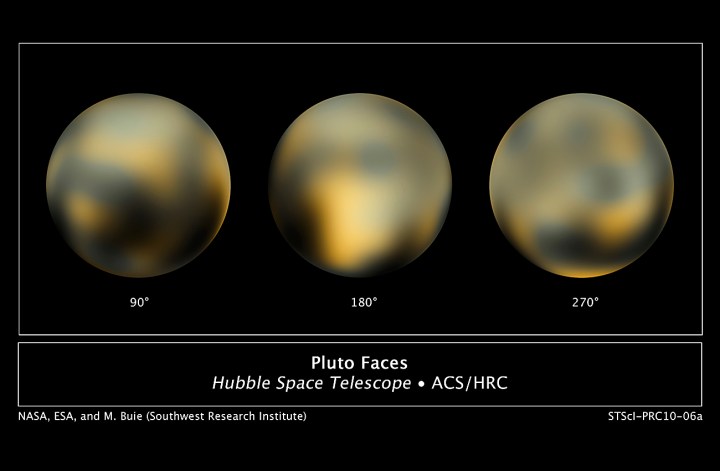

Main photo: A combination picture of the most detailed view to date of the entire surface of the dwarf planet Pluto, as constructed from multiple NASA Hubble Space Telescope photographs taken from 2002 to 2003 are seen in these images released on February 4, 2010. Hubble reveals a complex-looking and variegated world with white, dark-orange, and charcoal-black terrain. The overall color is believed to be a result of ultraviolet radiation from the distant Sun breaking up methane that is present on Pluto’s surface, leaving behind a dark, molasses-colored, carbon-rich residue. This series of pictures took four years and 20 computers operating continuously and simultaneously to accomplish. REUTERS/NASA, ESA, and M. Buie (Southwest Research Institute)/Handout

Well-worth watching: Neil deGrasse Tyson on his book, Pluto files

Become an Insider

Become an Insider