Media

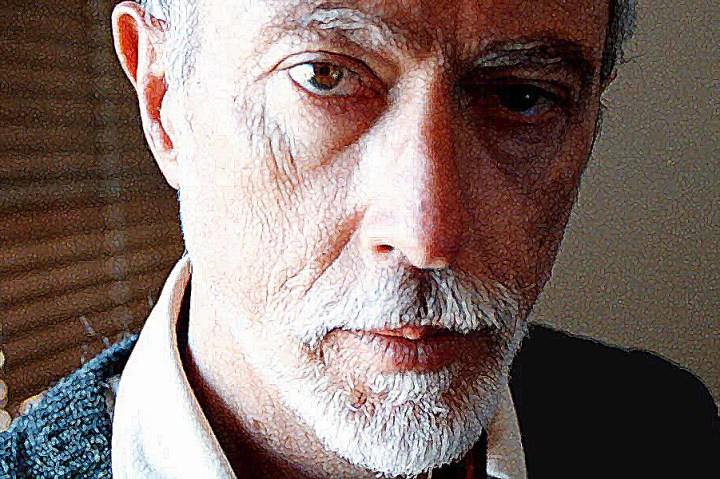

JM Coetzee at 70: fond regards to a champion South African

The Republic of South Africa’s undisputed giant of letters celebrates a milestone birthday today, and even though he left us for Aussie eight years ago – and hasn’t bothered to visit or call – we love and miss him lots. Big up, JM!

With at most four hours to get the story in, the endeavour is bound to fail. It’s John Maxwell Coetzee’s seventieth birthday today, and the task of adequately honouring the man requires a deadline of at least four weeks. One thinks here (ja, I know, but when writing about JM the formal and archaic “one” inhabits the voice like an undead literature professor) of Rian Malan’s famous non-interview, “The Prince of Darkness”. There sat Malan while Coetzee analysed the assumptions on which his prepared questions were based, unravelling each thread, until South Africa’s great journalist was reduced to asking its Great Novelist: “What kind of music do you like?” Coetzee’s legendary answer? “Music I have never heard before.”

That Coetzee is aloof, ornery, inscrutable and unapproachable is not news nowadays, and has not been for a long, long time. His contact with his South African publishers has for years been of the one-sentence variety, no salutations or niceties included: “Send two copies of Disgrace to my daughter.” His personality, when he does grant interviews or make public appearances, is noteworthy for nothing so much as its flatness of affect, its echo-chamber or cipher quality. Even his Nobel Prize banquet speech, which took the form of a tribute to his late mother, concealed more than it revealed: “Mommy, Mommy, I won a prize!” “That’s wonderful, my dear. Now eat your carrots before they get cold.”

Coetzee, of course, has been diligently eating his carrots for decades now. He started teaching himself to write fiction at the age of 29, when he was assistant professor of English at the State University of New York in Buffalo. He returned to South Africa in 1972, after his application for permanent US residence was denied, and took up a teaching post at the University of Cape Town, where his daily writing exercises continued. His first book, Dusklands, was published in South Africa in 1974. In the Heart of the Country, published in 1977, won for him the CNA Prize, then South Africa’s most prestigious literary award.

With Waiting for the Barbarians (1980), a remarkable and prophetic allegory of the relationship between oppressor and oppressed, Coetzee earned an international reputation. His masterful talent was confirmed by Life & Times of Michael K (1983), which won the Booker Prize. He followed up with the similarly lauded novels Foe (1986), Age of Iron (1990), The Master of Petersburg (1994), and Disgrace (1999), which again won the Booker Prize.

The latter, it will be remembered, was not at the time of publication the “hot read” of the ANC book club. Soon after Disgrace came out, Coetzee was lambasted by the ruling party for his portrayal of black South Africans as “immoral” and “savage,” and for his perpetuation of such stereotypes in the minds of white South Africans. Given that Coetzee was always a brave and vocal opponent of apartheid, was this the deciding factor in his subsequent decision to emigrate to Australia? Whatever the answer, the question remains a trending topic at South African literary soirees – characteristically, and poetically, the most Coetzee has said on the subject is the following: “Leaving a country is, in some respects, like the break-up of a marriage. It is an intimate matter.”

Another question local literary types like to ask, then, is whether Coetzee’s writing has been of the same standard since he was made, in 2002, an honorary research fellow in the English department of the University of Adelaide. In other words, does he still have his juice now that he’s removed himself from the creative crucible of his homeland?

It’s a tough one to answer, especially given that very few novelists are at their peak after 65, but for what it’s worth here’s my opinion – no. Neither Elizabeth Costello (2003) nor Slow Man (2005) nor Diary of a Bad Year (2007) nor Summertime (2009) are of the same level as the four, possibly five, masterpieces he penned between 1980 and 1999 (of the six abovementioned novels, only Foe and Age of Iron appear to lie outside the modern canon, with Foe, a wonder of intertextuality, closer to the cusp).

Still, all of the post-2003 books, especially Diary of a Bad Year and Summertime, can perhaps be deemed more accomplished in both form and structure than the best works of a host of lesser novelists, Martin Amis foremost among them. As Amis, in a frantic bout of publicity-seeking recently told Prospect magazine: “[Coetzee’s] whole style is predicated on transmitting absolutely no pleasure. I read one and I thought, he’s got no talent.” Of course Coetzee, the writer of the two whose literary legacy is not up for debate, had no reason to respond, and probably wouldn’t have if he did.

So happy birthday from South Africa, JM. We don’t expect a thank you note, but we hope the start of your eighth decade finds you well.

By Kevin Bloom

Read more: Nobel Prize banquet speech, “Coezee has not talent – author” in The Times

Photo: Reuters

Become an Insider

Become an Insider