Media, Multimedia

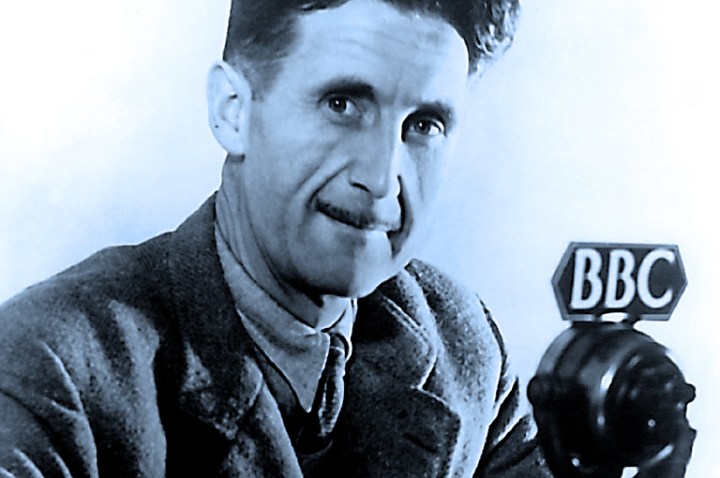

George Orwell: latter-day prophet or misanthropic toff?

Sixty years ago today, George Orwell, author of Animal Farm and Nineteen Eighty-Four, died of tuberculosis. Seeing he bequeathed his surname as an adjective to the English language, it’s probably worthwhile considering his life and legacy.

In four hyphenated words, published in 1937 in The Road to Wigan Pier, Eric Arthur Blair said all there was to say about his family’s social class – and as an intended consequence said a whole lot more about the nature of British class structure in general. The Blairs were “lower-upper-middle-class” he wrote; the implication being that they were not to be confused with the slightly (but perceptibly) more refined members of the middle-upper-middle-class, or, heaven forbid, the infinitely less aristocratic upper-middle-middle-class.

The Blairs, you see, stretching back to Eric’s grandfather, had served the British crown in imperial India; while they led a fairly privileged and pleasant life as administrators of Empire, they were not themselves landowners with extensive investments. In 1907, when the family returned to England, young Eric was sent to a private prep school at some financial burden to his father. At the age of thirteen, it was not inherited wealth that took him to Eton, but a scholarship.

Even so, Eton bored Eric half to death. For five years he barely opened a prescribed text. Out of 167 pupils writing final examinations in his year, he placed 138. The reason? From the age of six Eric knew he wanted to be a writer, and Eton didn’t offer English literature.

So while his classmates went off to Oxford and Cambridge, Eric, who failed to win a university scholarship, joined the Indian Imperial Police. He resigned in 1927 for two reasons: the life of a policeman in Burma got him no closer to his lifelong goal than had Eton, and his political consciousness had begun to play up – as he would write some ten years later, he wished to “escape from…every form of man’s dominion over man.”

Which meant that in his mid-twenties he was a penniless and near-starving dilettante camping out in a filthy bed-sitter on Portobello Road. No matter. In 2003, Terry Eagleton would write this about him in a 5,000-word feature in the London Review of Books: “[George] Orwell never seems to have taken the least interest in success, in contrast to those contemporary literary pundits who pride themselves on being plain-speaking, loose-cannon dissenters while cultivating all the right social contacts. Failure was Orwell’s forte, a leitmotif of his fiction. For him, it was what was real, as it was for Beckett. All of his fictional protagonists are humbled and defeated; and while this may be arraigned as unduly pessimistic, it was not the view of the world they taught at Eton.”

Eric Arthur Blair became George Orwell on the publication (in 1933) of his debut work, Down and Out in Paris and London. The first part of the book is an account of his days living on the breadline in Paris, where he worked as a dishwasher, and in the second part documents life in London from the perspective of the city’s tramps, amongst whom he spent much time. The pseudonym George Orwell didn’t mean a lot superficially – as he told a friend, “It is a good round English name” – but symbolically it meant everything: a shape-shift from the old Etonian colonial policeman into the vocal and radical anti-authoritarian leftist.

Until his death from tuberculosis on January 21st 1950 – sixty years ago today – Orwell remained a dedicated socialist, despite repeated accusation that he’d betrayed the left. In 1936 he fought in the Spanish Civil War against Franco, and while his experiences there showed him that socialism in action is a human possibility, he also learned that the Stalinist left could (and would) betray the common people. It was this first-hand experience of betrayal that formed the nuclei for his two great works of Stalinist satire, Animal Farm (1945) and Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949).

“Some animals are more equal than others” and “Big Brother is watching”: these are easily the two most famous neologisms coined by George Orwell. They’re as relevant today as they were in the 1940s; so relevant, in fact, that while the former serves as a failsafe metaphor for successful liberation movements everywhere (everybody’s equal until the liberation movement becomes the government; think ANC etc.) the latter has taken on new meaning as a genre of mass-market, highly-profitable entertainment (a double-irony given that Orwell, who correctly predicted how intensely governments would one day watch us, is also supposed to be the father of modern cultural studies).

Was Orwell then a latter-day prophet, as a number of prominent intellectuals, including Christopher Hitchens, would have us believe? Eagleton reminds us there’s another side to the legacy: “The case for the prosecution is that Orwell was a self-mythologising romantic toff who went in for the odd spot of sentimental slumming, sometimes adopting a ludicrous Cockney accent in the process, and ended up in political defeatism and despair. A second-rate novelist and a furtively fabricating social commentator, he was homophobic, anti-feminist, unsociable, anti-intellectual, authoritarian and latently violent. He was also an anti-semitic, sexually promiscuous, self-pitying Little Englander, whose later fantasies about Big Brother and pigs running farms (they don’t have the trotters for it) bequeathed a set of lurid stereotypes and convenient caricatures to the Right.”

Quite. Whichever side you’re on, though, there’s no getting away from the fact that the man’s surname is now an adjective. A big whack of George W Bush’s policies were described as “Orwellian” – as are London’s ubiquitous surveillance cameras, and North Korea’s, well, everything.

The word, which is often used to describe anti-libertarian government policy, is also used to refer to obviously self-contradictory ideas and thought processes that are nevertheless accepted as true by the one uttering them. To say that Julius Malema is an Orwellian leader, then, might not be to misappropriate the term.

By Kevin Bloom

Read more: Terry Eagleton in the London Review of Books

Watch: “1984” movie trailer:

Watch: 1984 Apple’s Macintosh Commercial

Become an Insider

Become an Insider